Kristine Potter in conversation with Matt Dunne

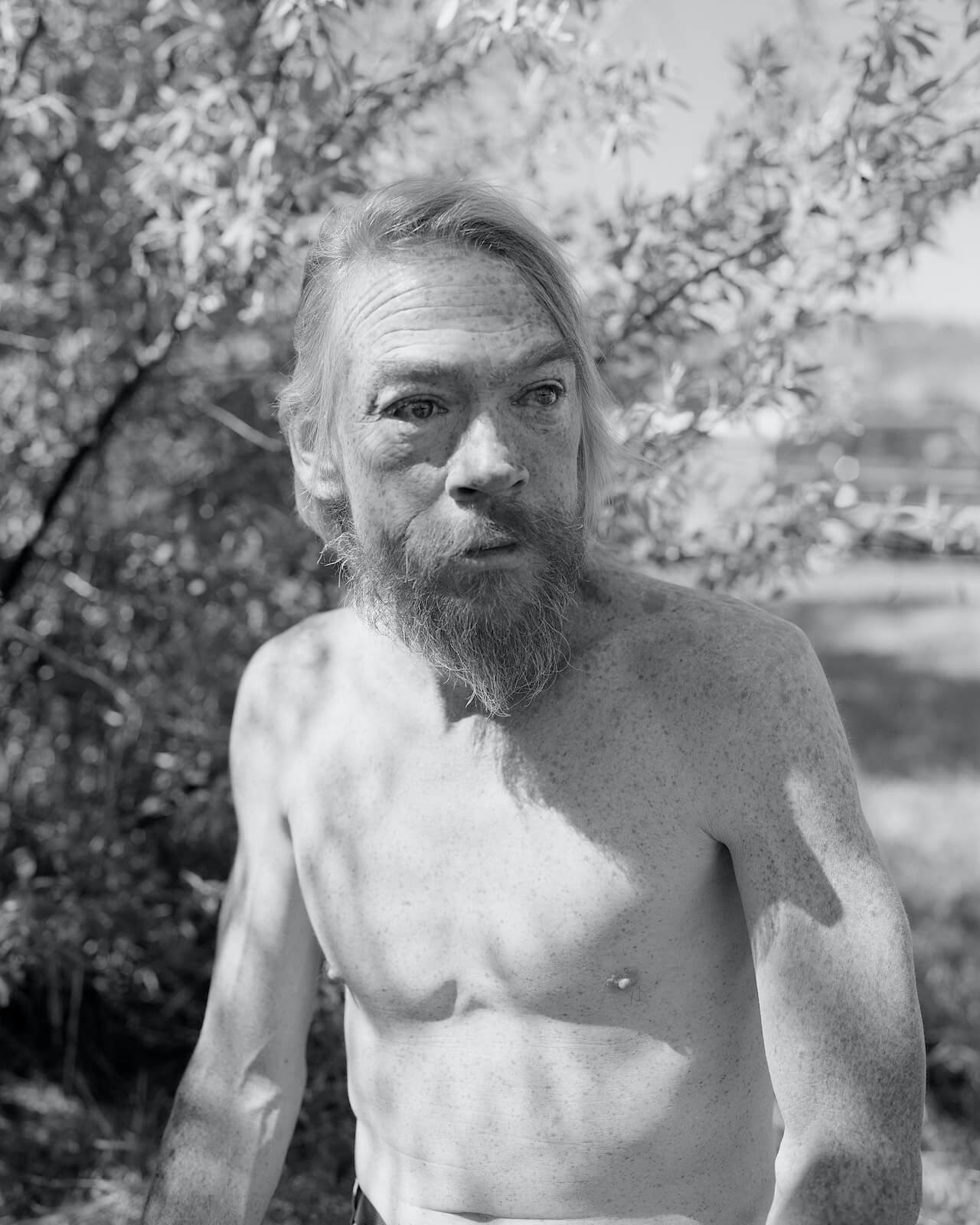

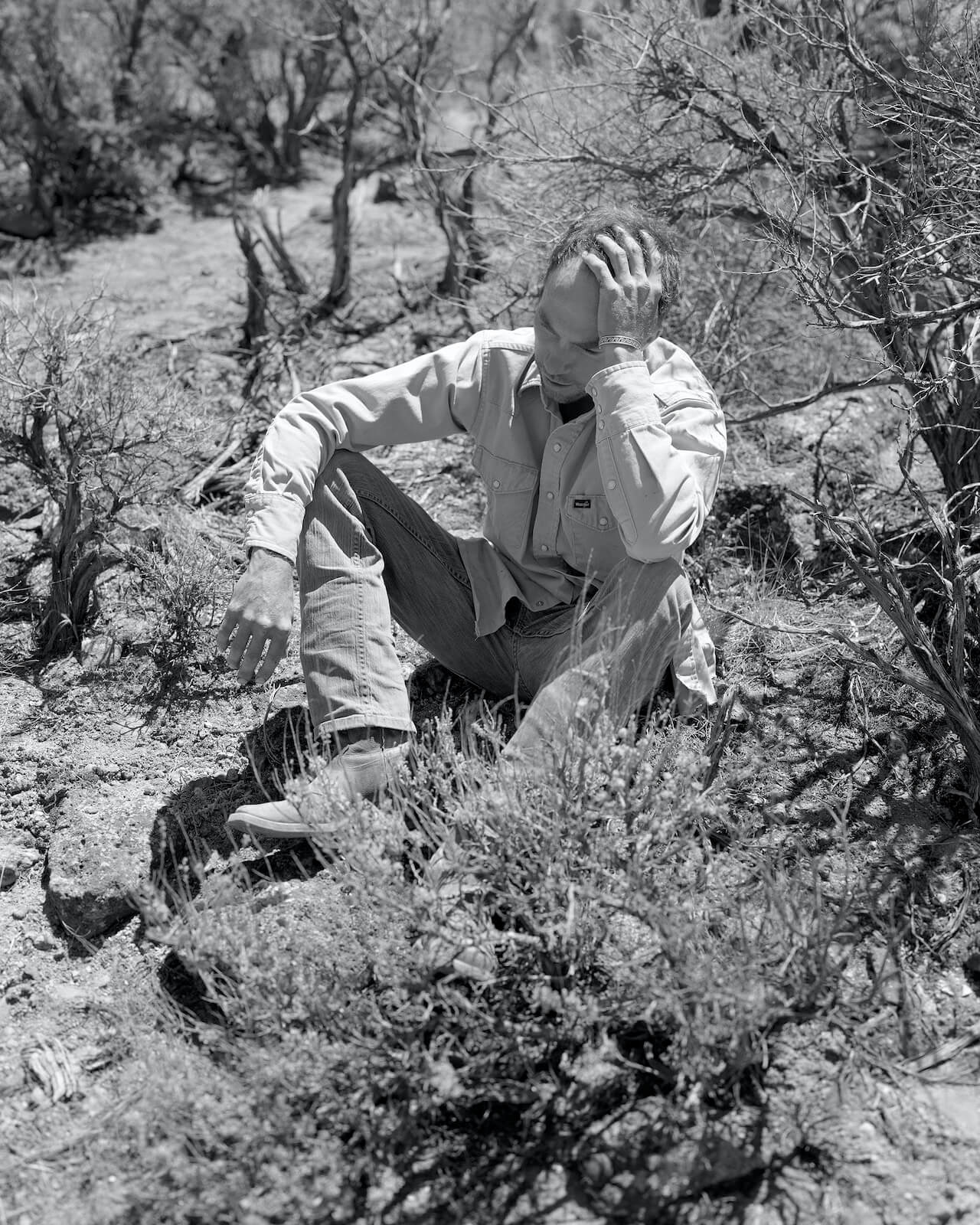

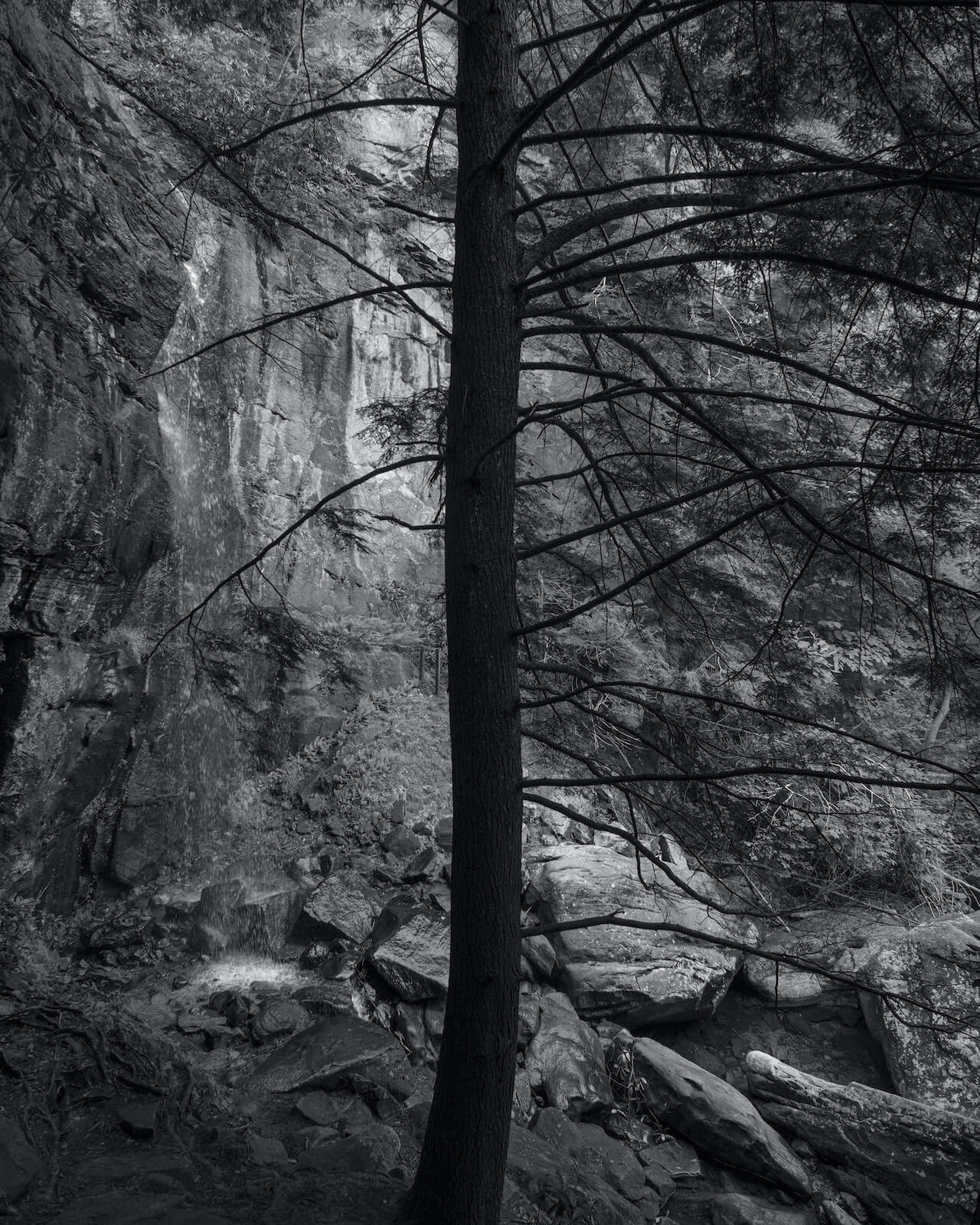

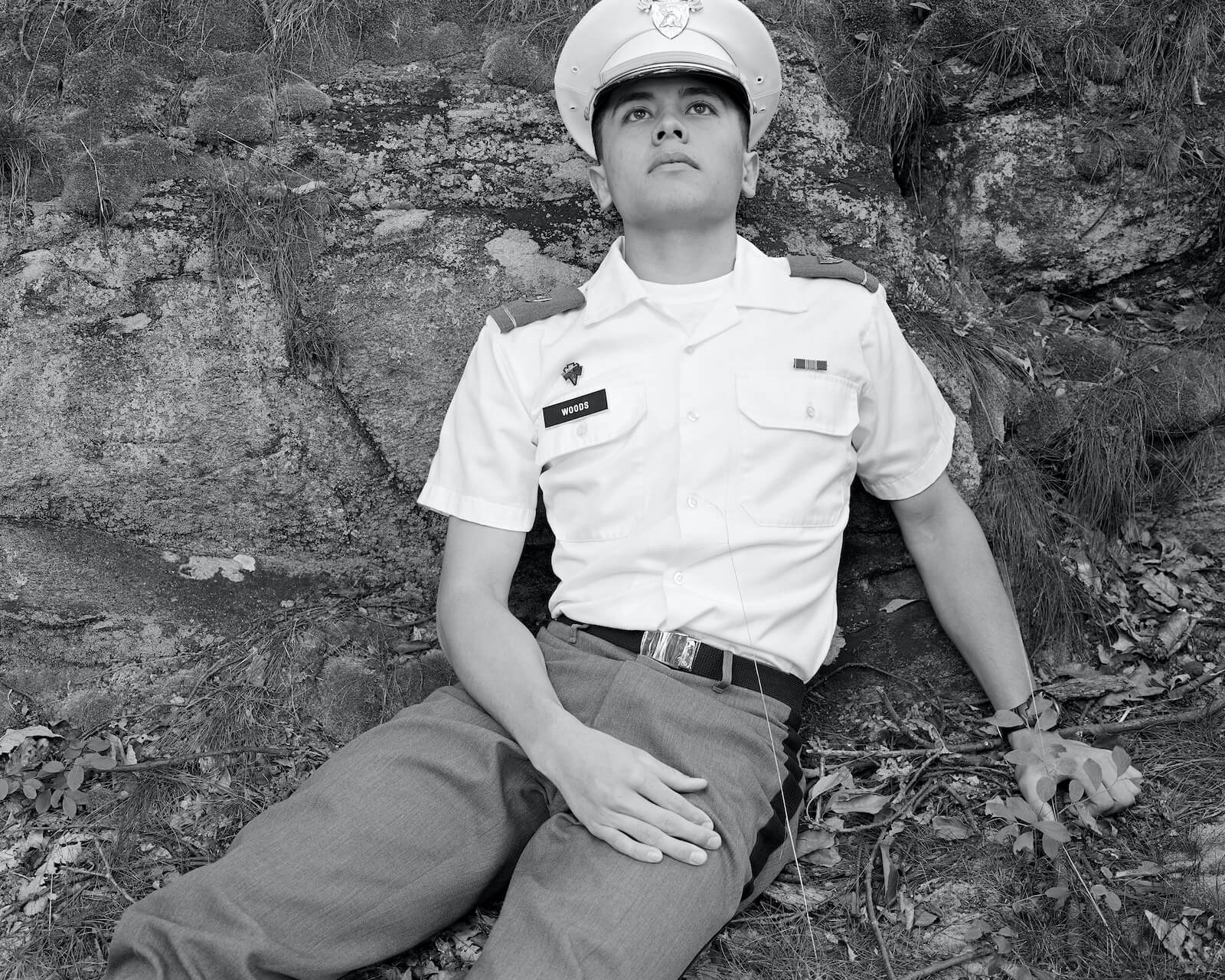

Kristine Potter is an artist based in Nashville, Tennessee, whose work explores masculine archetypes, the American landscape, and cultural tendencies toward mythologizing the past. Her previous work has focused on young male military cadets (The Gray Line) and the relentless danger of the American west (Manifest). Both of these series reframe the mythology of indomitable men and explore the bleed between human violence and natural threat. In her current body of work, Dark Waters, Potter uses film, image, and sound to depict threatening waters and the people around them. This work investigates a feedback loop between nature and myth: how a threatening landscape primes a culture for violence, and a violent culture projects threat onto a landscape. Potter was awarded a MFA in photography from Yale University in 2005. She is a 2018 Guggenheim Fellow and the current awardee of the Grand Prix Image Vevey. Her first monograph, Manifest, was published by TBW Books in 2018.

Matt Dunne is an educator, photographer and writer living in Melbourne, Australia. He has a Bachelor of English Literature and a Masters of Teaching. He writes about photography, nature and Australia at Tending To The Garden.

Matthew Dunne: A lot of your work has been explicitly about masculinity – trained and wild – why are you interested in masculinity? Where does that interest come from? How has it developed or changed over time?

Kristine Potter: I’m not sure if I can tell you precisely why it interests me. I just know that it does. I think it has something to do with growing up in a military family and with all brothers. My mother, the only other woman in my immediate family, also grew up with all brothers and a military father. I suppose I felt there were a lot of unexamined behaviors and expectations at work around me. At the outset, I went directly for the type of masculinity that had been modelled to me; the military man. My initial plan was to look at how that sort of personality was formed. But as the project The Gray Line progressed, I became more interested in interjecting ambiguity and nuance into a structure that largely avoids indulging either. I could see that just by paying attention to the cadets’ full expressions and mannerisms, I was pushing the limits of how soldiers are typically seen. It’s subtle and expansive at the same time. With the men out West, I was reacting more to a mythological ideal. The John Wayne, Clint Eastwood-esque version of the American man was on my mind. I was in pursuit of broadening the way we see the men who make their lives in remote areas of the American West.

MD: Two of your projects circle the way people relate to place and space. Does Manifest Destiny, the widely held belief in the 19th-century United States that its settlers were destined to expand across North America, still define the West? Does the history of violence still echo the way people read landscape in the South? When you’re exploring and experiencing the land, is the history present for you in the moment?

KP: I sense there are echoes in the landscape. Things that have transpired in the past have a way of resonating again and again. It’s a feeling, really. But I think it charges our cultural output. I believe it is why certain stories get told and written, and why certain sounds and songs are created and reinterpreted over the ages. It all creates a feedback loop… Where we can no longer tell whether it is our cultural ideas that make us see the landscape in a certain way, or whether the history of a place (felt or learned) creates a context for how we express ideas about it.

MD: How do you make work that’s informed by history, culture, that feedback loop, without it falling into predictable or cliched territory?

KP: I’m always thinking about the way things have been seen, and I’m trying to contribute a new way. Sometimes that is just a slight shift, sometimes it is more dramatic. Sometimes the contribution is more of a technical one, rather than conceptual. I’m interested in all of it; the ideas, the tools, and the experience of the physical print.

MD: How does that process work? Are you constantly reading and finding old images to refer to or is the research different in form? How do you do justice to the layers within a story? Was this approach something that you developed during your time as a graduate student an as it evolved since then?

KP: I am constantly looking at images, past and present. I’d say that if I’m trying to find a new way to see something, it is because I have felt a lack of it in the materials I’ve explored. I’ve got blind spots of course, I don’t claim to have an encyclopedic knowledge of what’s been made. But sometimes I do feel compelled to respond to a certain lineage of looking. I’m not sure when it developed, exactly, but graduate school certainly held my feet to the fire in terms of authenticity.

MD: What pulled you out West? How similar or different is that to the motivations of manifest destiny and the impulse of photographers for generations to find and capture the sublime?

KP: I won’t deny that as an East coaster, I had an almost insatiable desire to head West and explore. I do think it is part of the American ethos. But the real truth of why I ended up embarking on that project had more to do with a set of personal histories and circumstances. I was finishing up work on The Gray Line just as my family inherited a bunch of ephemera associated with my great-great-grandparents. They were sharpshooters in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, who toured with Buffalo Bill’s show before creating their own. They travelled all over the eastern U.S. and much of Europe, extolling the “virtues and aptitudes” of western expansion. It got me thinking about the construction of that mythology, and how all of the violence required to secure new land got turned into an exhibition for entertainment and the construction of a new national identity. Interestingly, the advent of photography aligns perfectly with the notions of Manifest Destiny. So while all of this is happening, we are also seeing photographically for the first time, the “sublime” American West. Those pictures by Carlton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan (to name just two) are incredible, and it was an extraordinary feat to make them. I began to see that entire continuing history of the vista-view landscape as functioning repositories for our dreams and ambitions as a nation. I felt that as a woman in 2012, my contribution would be to respond to that area differently. I wanted to feel it, rather than project onto it.

MD: This is a weird question, but I was thinking about how colonisation is often criticised yet its legacy is preserved, at least here in the States. Do people have to create and sustain a myth that invokes domination in order to desensitise themselves from the guilt of their destruction?

KP: Yes, I absolutely believe that is true. I also believe the mythologies grant us a kind of permission to continue to be violent. What’s most fascinating to me is how those ideas are not just operating world-views, but how they are delivered and received through entertainment.

MD: And are we conscious that entertainment sustains violent myths? Do we want to be? Do you think people in the States value violence or rather value the attitudes that lead to it?

KP: I’m not a social scientist, so this is primarily based upon my observations. But no, I do not think most people give much thought as to why they’re attracted to violent forms of entertainment or why the South in particular seems infused with more outright daily violence than other parts of the country. (That is statistically true, though the numbers are complicated.) There is a lot at play, historically and culturally. Violence is generally about asserting control and the South has a particularly fraught relationship with that idea. I think one of the areas of Southern history that seems less mined than others, is that of gendered violence, of men asserting their ultimate control over women. This is a more universal example, but there was an article in the Guardian recently which revealed that given the option of literally thousands of films and TV series, many viewers will opt for ones that center around a dead (raped, molested) girl. Netflix, like most media companies, is interested in profit. So why not just give the audience what it desires? I see a through-line of violent exhibitionism from those early murder ballads, to the wild west shows, to the contemporary landscape of cinema and tv. Culturally, we seem to require it.

MD: In Dark Waters you’re exploring violent waterways, in what ways are these spaces violent? Is there still a culture of violence in these spaces?

KP: I’m exploring bodies of water that have violent names. “Murder Creek,” “Bloody River,” “Deadman’s Pond,” that kind of thing. In many cases, the provenance of those names has been lost to history. In other cases they are well documented and usually relate to the violence incurred during the early colonial period. I’m less interested in their specific histories than I am in the sheer preponderance of their existence in this part of the country. It’s as if the landscape is marked by our endless violent campaigns. The landscape itself is also demonstrably more dangerous than say… That of New Hampshire. It can be dark and beautiful. There’s a tension there that interests me.

MD: One thing I’m curious about is how being awarded the Grand Prix at Vevey Photo Festival influences the work and the process. With some form of recognition and deadline, how does that affect the project’s development? Do you work differently on a project with that feedback and future life for the project?

KP: It’s been more influential than I could’ve imagined. First, it’s just incredibly reassuring to have some really brilliant people believe in the work. The jury was comprised of Dayanita Singh, Lesley Martin, Emma Bowkett, Christoph Wiesner, and Francesco Zanot. In the all-too-prevalent days when I’m convinced nothing is working, I can be reminded that at least in some iteration, the work is compelling. Of course finding the right, final iteration is the hard part and I take that very seriously. Having a deadline is the classic double edged sword. It’s motivating and foreboding at the same time. Amazingly, the team at Images Vevey are really wonderful. Raphaël Biollay and Stefano Stoll are so supportive and they keep reminding me that Vevey is a place to experiment. They’ve really encouraged me to play with ideas that may or may not continue to be a part of the work after the festival. I’m working in video for the first time. We’re building an installation. I’m thinking a lot about how the photographs will be encountered, what the room will feel like, and what sounds might also exist. They say… Let’s think Big! Let’s try it! It’s an incredibly exciting opportunity and I’m just really, really grateful.

MD: Your photographs, and a lot of western art in general, is often concerned with something ugly and violent. I’ve often struggled to understand why we are collectively drawn to those often disturbing things. How would you respond to that? Is this a process of curiosity or healing for you?

KP: That is a question I ask myself too… Why are we collectively drawn to these things? I don’t have an answer. The process of making this work is a few things for me. It is exciting and sometimes dangerous. It can be arduous and disappointing. It is absolutely tied to curiosity. And for the part of the work that is dealing specifically with music and the stories of these women who’ve been killed and sung about, it is redemptive.

MD: I want to ask a bit about your process for making work. Are you a walker or a driver? How do you schedule in trips to make photos and what do the days look like? What about editing, do you have routines, rituals or processes to get along with that?

KP: I drive a lot. Too much. It is particularly true right now, as the work is geographically more diverse than earlier projects. I’m traveling around the greater southeast, which includes Kentucky, The Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida and Tennessee, where I’m living. But once I reach a destination, I’m a walker. So I do both. It was during the making of Manifest that I got into the habit of listening to audiobooks while on long drives. I listened to practically every western-based Cormac McCarthy book during the making of those pictures and I think it absolutely changed the way I saw the landscape. When I pivoted to making work in the southeast, I started again with McCarthy, but picked up his southern novels. He’s my co-pilot. When out walking, I’m just looking for the potential for pictures everywhere. It’s a very particular kind of focus which I find I do best alone. I’ve never been someone who can work with an assistant, unless it’s an editorial gig or something like that. I’m a slow worker, I think. It takes me time to sit with work before I can be convinced it’s any good. I make a lot of small prints and push them around for a good, long while before committing to them. I enjoy the latency of film, and pretty much apply it to my digital workflow as well. It’s not unusual for me to shoot digitally and not look at the pictures for weeks. I just like to have space in between the act and the revelation.

MD: When you’re walking or driving, what are you thinking about? What’s your internal voice saying and how does that relate to where you direct the camera and how you make photographs?

KP: I believe in listening to the inner voice, and mine typically directs me where to go. I try to follow it as much as possible. Recently, I’ve had episodes where my instincts are telling me to leave an area because it isn’t safe. That really has to do with who else is around. Who is down by the river. Who may or may not be in the forest. It’s like when the hairs go up on the back of your neck and you’re not sure why but you decide to abide. But most of the time, I’m alone and just looking for opportunities to make pictures. I like to be as open as possible. That openness means that all kinds of thoughts cross my mind.

MD: Could you tell us about something unexpected or bizarre that’s happened while out looking to make photos?

KP: Well, I can tell you something funny. I was out in Colorado and decided I wanted to try to make some night landscape pictures way out on top of a very remote mesa. I had a bunch of strobes and my 4×5 and spent several hours trying to figure out how to make pictures in the dark – it is practically impossible to focus, thus most of the pictures were terrible. But the next morning I met a guy at a cafe who I wanted to photograph. While pitching my plan to him, I told him about other pictures I had been making, including a recap of my previous night on the mesa. He looked at me with complete puzzlement, which typically means someone doesn’t understand my motivations. So I kept explaining. Finally he interrupts me to say… “Yeah, but what are you doing about mountain lions out there?” I’ll be completely honest, it literally never crossed my mind, and my face clearly said that without having to use words. I naively thought that if anything was potentially dangerous, it was the men I was photographing out in the middle of nowhere. (That was the New Yorker in me.) So he then says… “Well if you want, I can come out with you next time and bring a gun. I can stand watch.” To which I replied “Ok yeah, that sounds great!” Something a New Yorker would think was absolutely insane, ha. So we went out that evening. Turns out that if I’m alone at night on a mesa with a guy, I will make pictures of him instead of trees.

MD: Apart from making personal work what other avenues do you have to making ends meet? How have you balanced the needs of time, materials and money in your life and art practice?

KP: I’ve taught at University for many years. That was my main source of income for a long time. Since moving south, I’ve done it considerably less and have made ends meet with editorial work and fellowships. I think I’ll circle back around to teaching when the time is right. But for now, it has been a good change to have more flexibility in my schedule for making work.

MD: I’ve noticed that a lot of your work and thinking and process is very informed by the USA and its history, have you ever thought of working somewhere else? Would it be very different?

KP: I lived in Paris, France for a few years before graduate school and I made a good deal of work. I’m going to make pictures wherever I live. But you’re right, I am deeply interested in the complexities of American culture and its history and it just seems like a well that is not nearly exhausted.

MD: Where do you see your work heading in the next few years? Are there any ideas or projects you’re waiting to get working on, or are you heading back into teaching?

KP: I’ve got a few ideas simmering but nothing I feel comfortable putting into words yet. I will say that my practice is broadening and I’m becoming interested in moving image and sound. I’ll probably also be heading back to teaching. It’s a practical way to make a living that (given the right conditions) can be really rewarding and doesn’t entirely suck the life out of you. And what else? I can never really know.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.