Cat Lachowskyj

Cat Lachowskyj is a Canadian writer and editor based between Athens and Toronto. Prior to writing, Cat trained as a photo archivist in Toronto, analysing albums housed at the Archive of Modern Conflict. Her writing has appeared in numerous publications, including The British Journal of Photography, Rvm Magazine, Foam Magazine, American Suburb X, and AnOther, and she has written a number of essays for artist books and compilations. Her current research interests involve psychoanalytic approaches to photography and archives, and she is currently training to become a psychotherapist. Cat is also the editor of the Unless You Will Journal.

Close to the Knives – David Wojnarowicz

I feel zero hesitation in stating that David Wojnarowicz is my favourite artist. The primary downfall of forging a career in the arts is slowly finding your personal interests entangled with paying your bills, inevitably snuffing out a multitude of your internal flames. Commodifying my passions has resulted in a handful of my interests dissolving into the ether, but Wojnarowicz is someone whose work impacts me today with the same intensity as my first encounter. Close to the Knives was the first of his books I read, and its impulsive internal meanderings and raw expression of frustration and helplessness are gutting. We’re taught that anger and rage are shameful, but Wojnarowicz reminds us that this fire often emerges, in our darkest times, as a necessary companion.

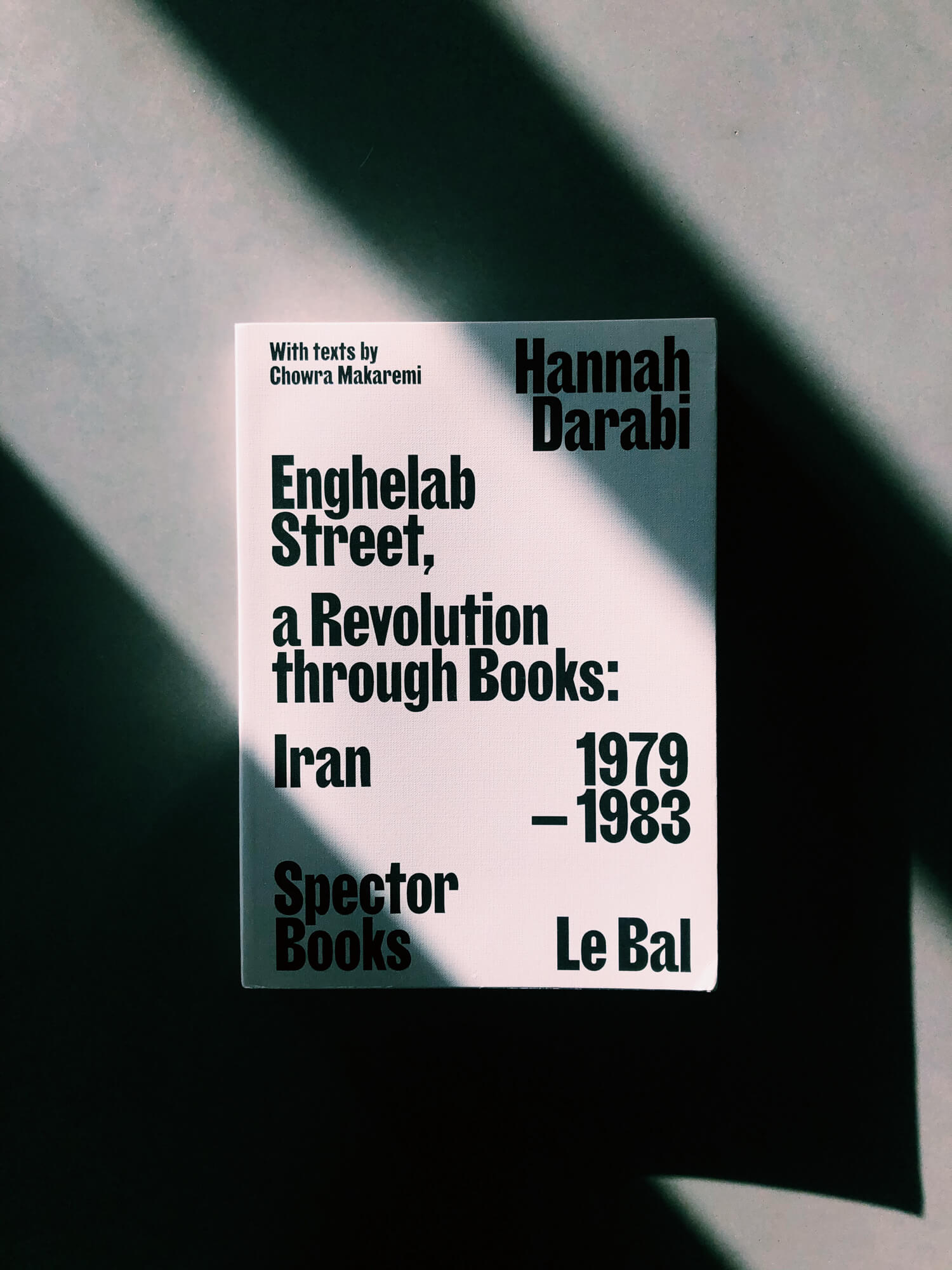

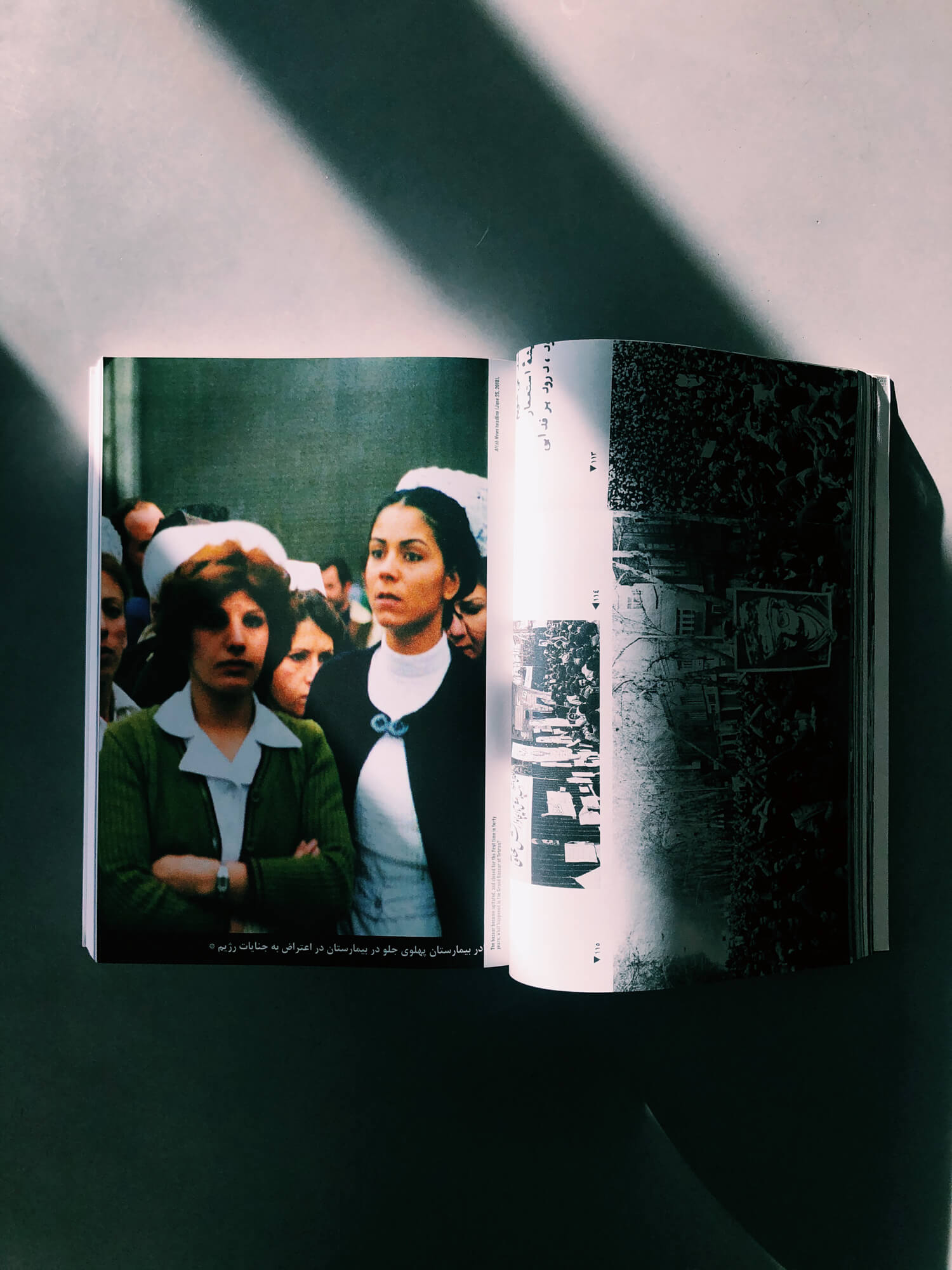

Engelhab Street, a Revolution through Books: Iran, 1979-1983 – Hannah Darabi

A number of artists engage with archives, but I have a particular affinity for Darabi’s work because it’s backed by relentless research, thoughtfulness, and critical construction. This book is an archive in itself, specifically tracing the bookmaking practices and independent publishing coursing throughout Tehran’s Engelhab Street between 1979 and 1983. The project is particularly special because it’s about the sentience of Darabi’s objects, charged and resurrected through her meticulous collecting, which itself energizes her own creation from cover to cover. Engelhab Street is about the lived experience of books, brought to life through the magic and intent of each maker’s fingertips. I always refer to this work as a necessary blueprint for future histories of photography.

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments – Saidiya Hartman

A conversation about radical engagement with archives would be incomplete without discussing the work of Saidiya Hartman—what a goddamn alchemist. Rather than presenting us with a quantitative analysis of linear histories, Hartman enacts what she calls “critical fabulation,” creating thick atmospheres and necessary nuance, restoring agency to voices silenced through the restrictions of societal, and archival, standards. Hartman’s style isn’t footnoted, but italicized, gently prompting her reader to flip to the book’s appendix for specific records on texts, documentation, and photographs. For anyone approaching this book for the first time, I recommend flipping back and forth between Hartman’s prose and citations; it makes the reading take longer, but it demonstrates how her queer and subversive form expertly embodies the individuals she breathes life into.

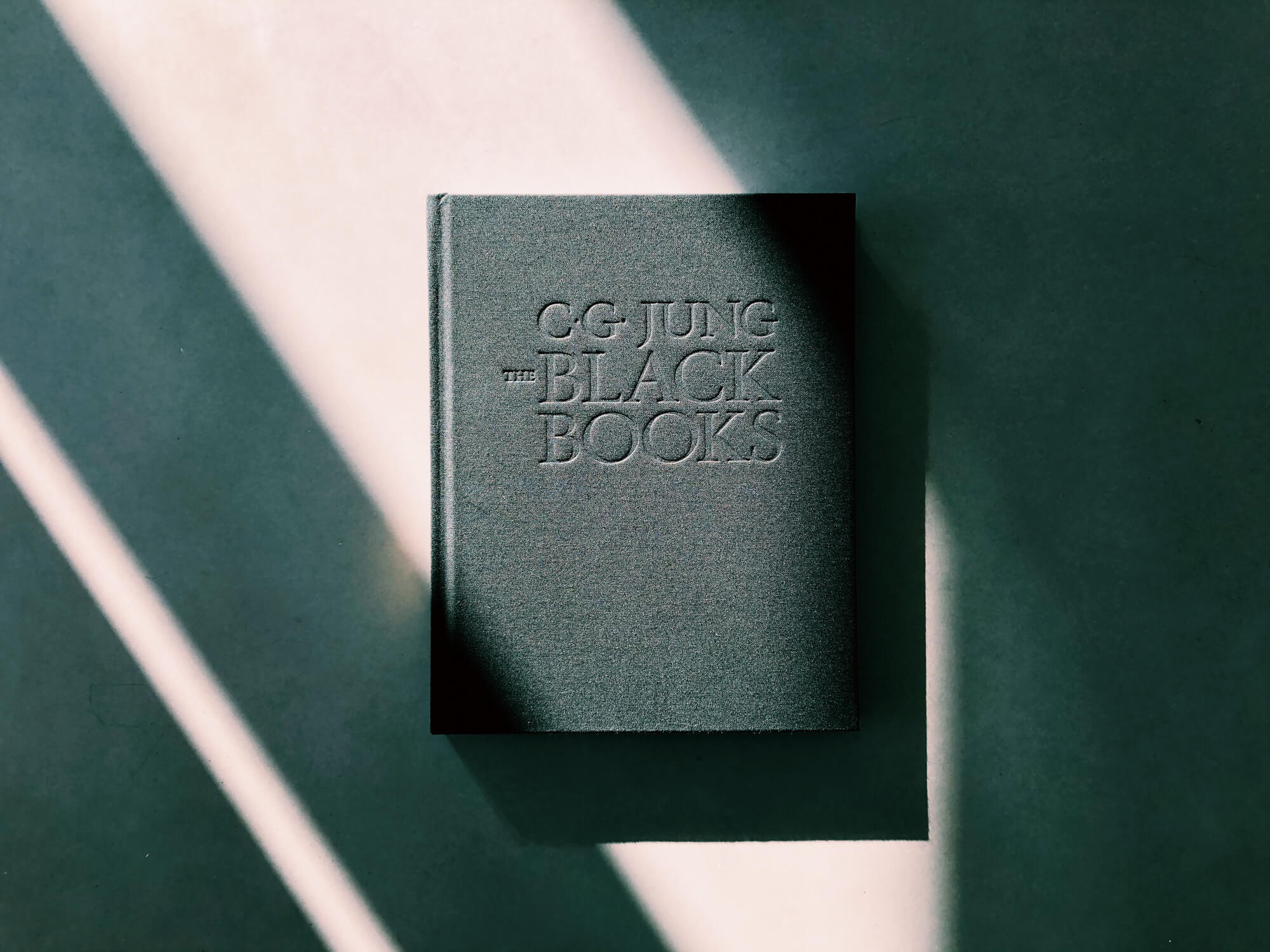

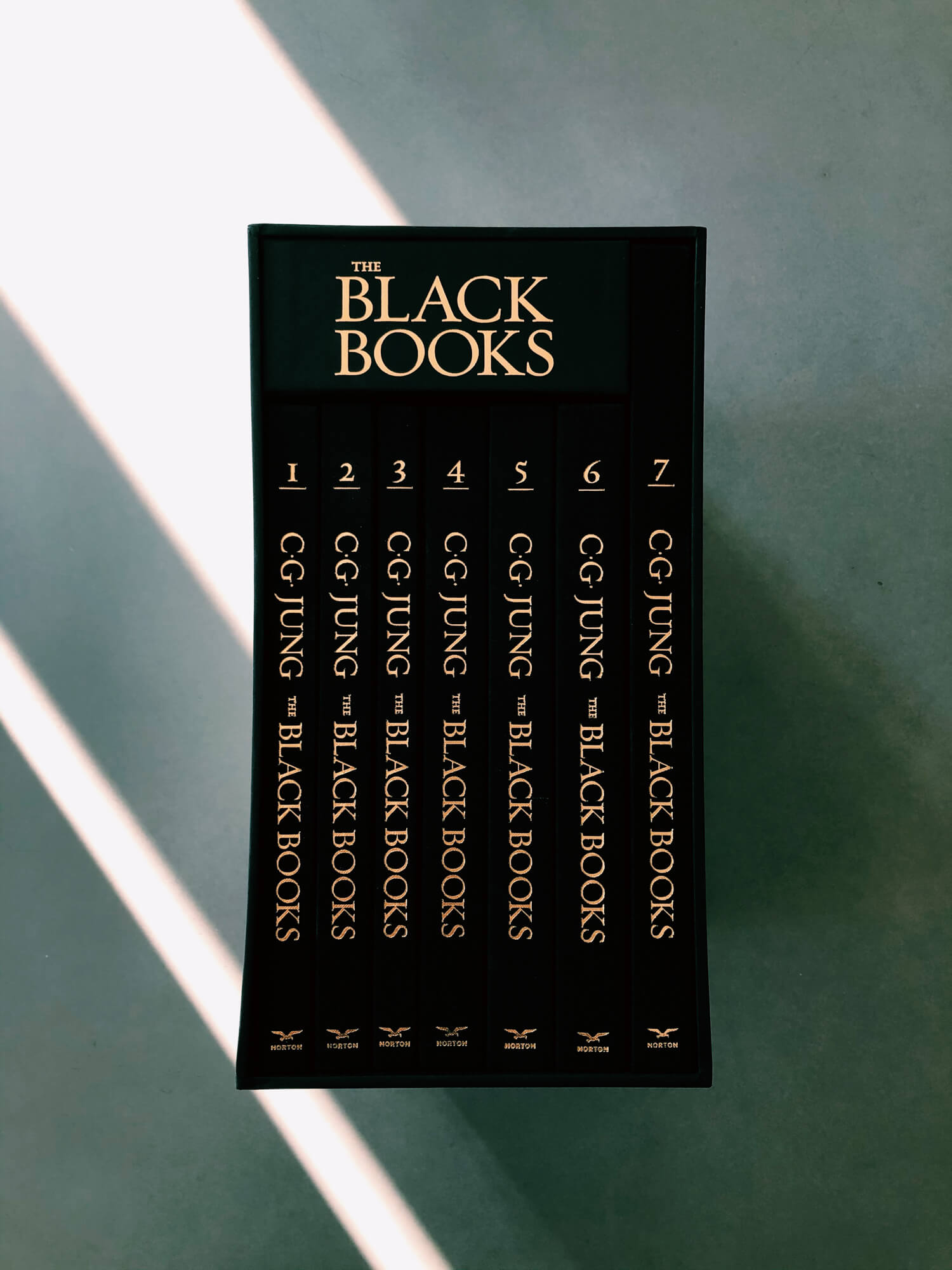

The Black Books can be described as Jung’s rough notes for many of his official works, including the renowned posthumous publication of Liber Novus. Sonu Shamdasani, the project lead behind The Red Book, has been working with the Jung estate for some time to finally publish the analyst’s stream-of-consciousness interactions with the many components of his inner world. These books aren’t comprised of edited and re-edited manuscripts. Rather, they are raw journals, and the production in this collection is an archivist’s dream. I love them for many reasons, including the fact that each volume contains dual information: the high-res scans of each journal page, followed by the editor’s typed transcriptions and translations. Do these count as photobooks? They are photos of journals, I suppose. The writing and mental wanderings are engrossing, and I’m a sucker for a cloth-covered box set.

I was gifted Nox for Valentine’s Day a few years ago by someone who clearly knows that the way to my heart is through anything having to do with death, grief, and loss. I love this object. So much of Anne Carson’s work feels like how we all might be writing and making things if we weren’t taught that play is only for children. Snippets of poetry, mutterings, snapshots, letters, and ephemera are all brought together in this wandering accordion-in-a-box. Nox drives home the preposterous Western fable of closure in the wake of grief, showing us that impactful events are simply part of us, inseparable from our flesh and being.

Processed with VSCO with c1 preset

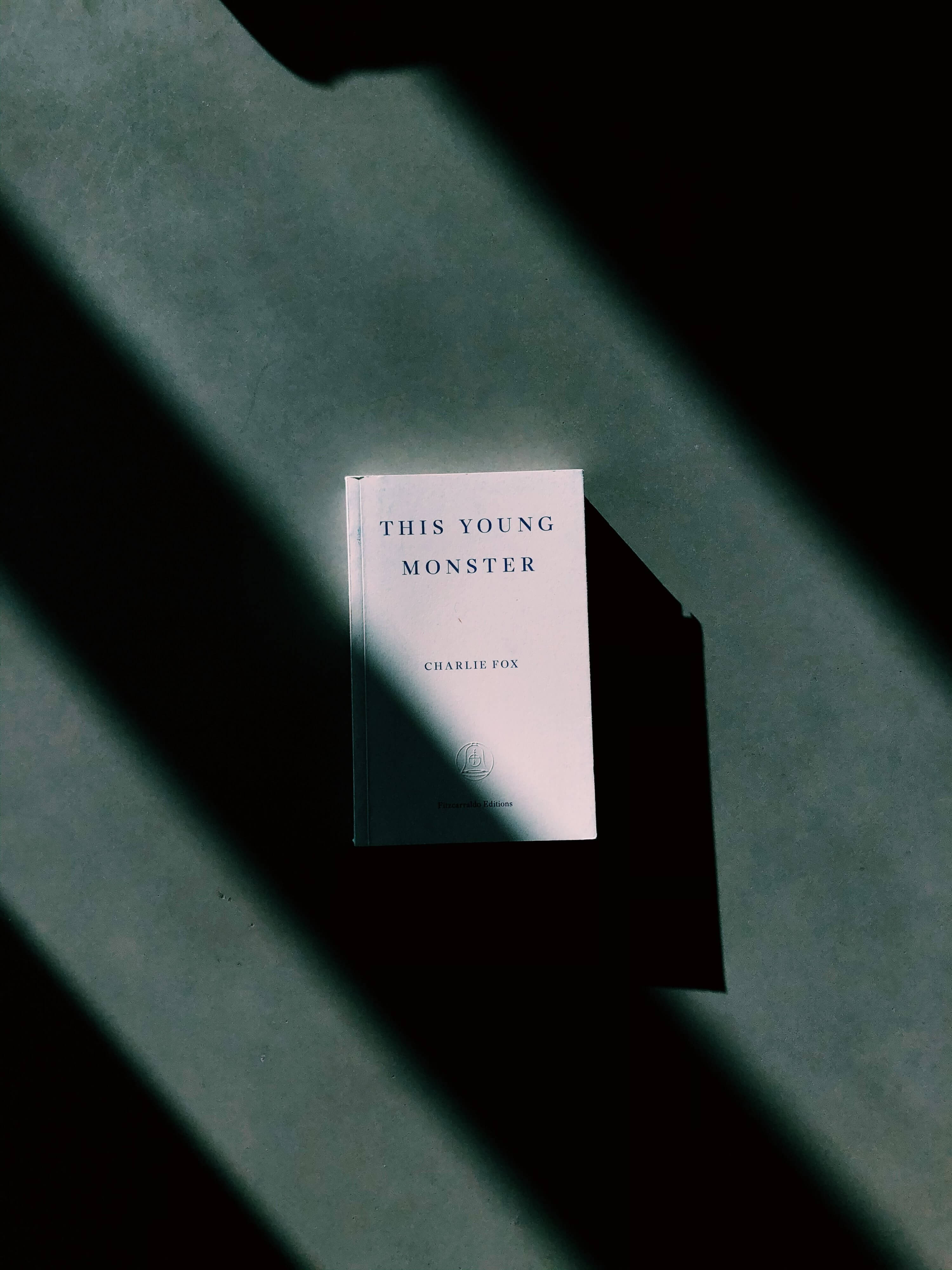

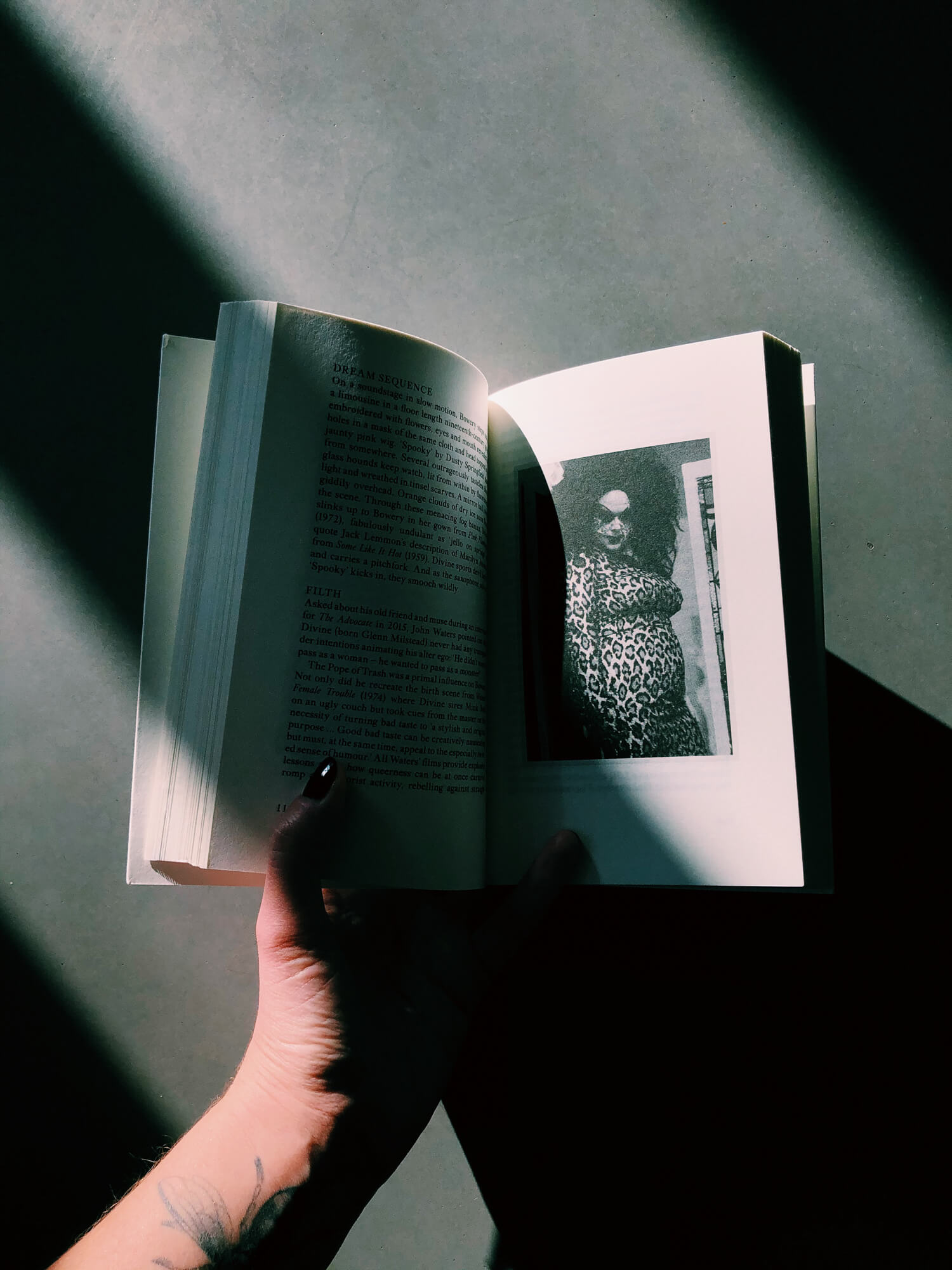

This Young Monster – Charlie Fox

This perfectly imperfect book of essays takes each reader on a journey through the chaotic lives of artists deemed monstrous, like Buster Keaton, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Leigh Bowery, Divine, Harmony Korine, and Macaulay Culkin, each dissected and explored through Fox’s simultaneously chaotic forms. These include letters, a script, and tumbling essays that are equal parts historical excavation and cultural criticism. Fox’s writing is quite a trip, and difficult to put down once you start, sparsely illustrated by black and white photographs that stand on their own as the contained spirits of each written piece. This book is rife with examples of how queerness is inseparable from our circumstances’ myriad other qualifiers, more prevalent than our imposed structures would have us assume.

I fucking love Alan Moore. Sue me. Watchmen is a worthy classic, and if you haven’t read (or re-read) it over the past twelve months, you should. Rorschach has evolved into a striking look inside the inner world of incels. But I’m here to talk about Promethea, a series of comics about the title character, called into the material world through storytelling. In twentieth-century NYC, Promethea is manifested through a college paper, written by protagonist Sophie Bangs, to summon the apocalypse. If you like esotericism, hermetics, mythology, or anything in and around the anima mundi, the art and narrative threads in this series are a joy. It can feel a bit like a bound version of Moore’s philosophical soapbox, but I love that shit, and each page is so packed and saturated with symbolism it feels like flipping through a grown-up version of the I Spy picture books.

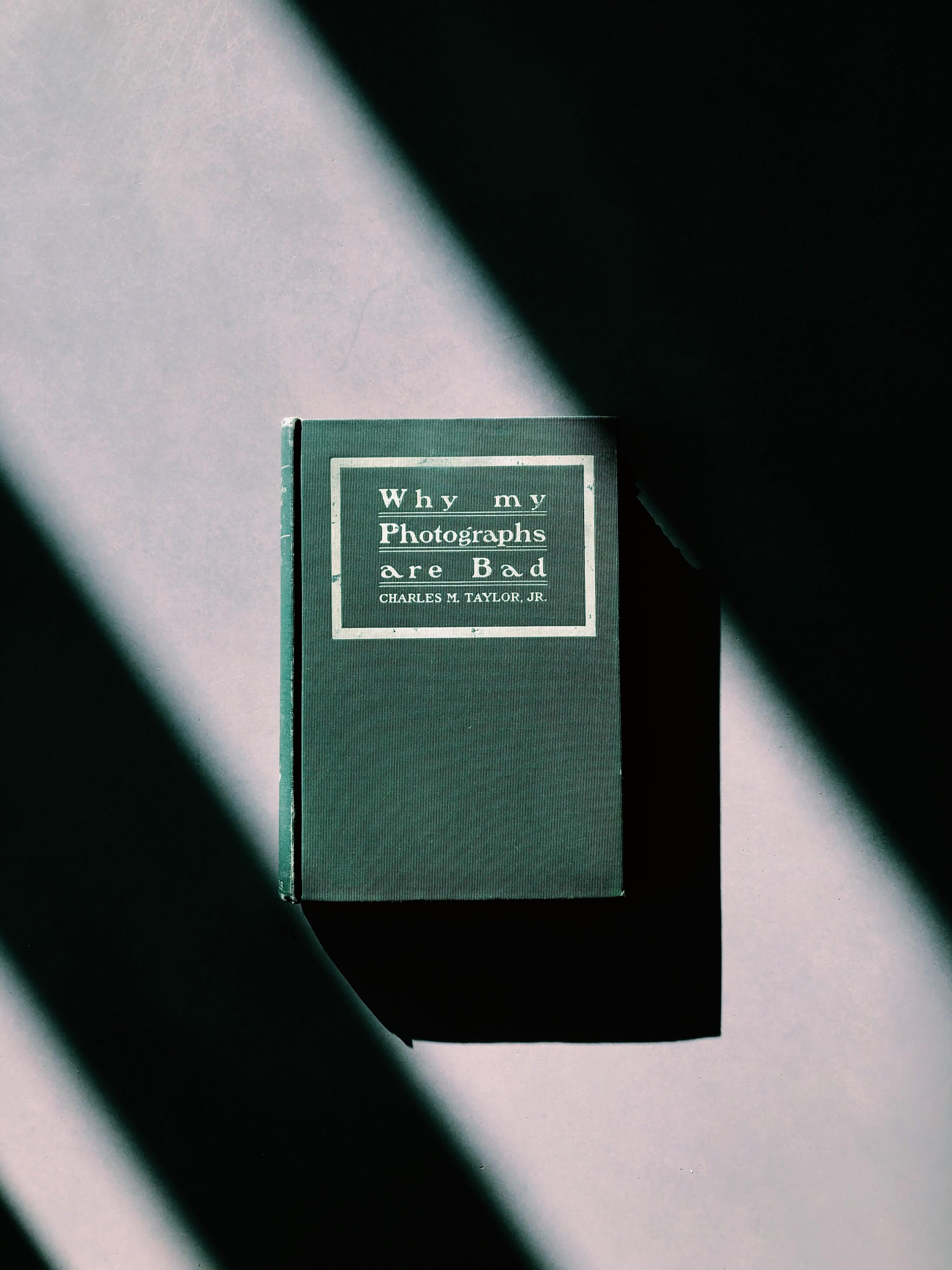

Why My Photographs Are Bad – Charles M. Taylor, Jr.

I stalked this book on eBay for about a year before I finally bit the bullet and bought it, and I’m so glad I did. Published in 1902 by Charles M. Taylor, Jr., its contents are quite literally what the title suggests. Taylor developed it as some sort of reverse manual for photographers; rather than a list of step-by-step instructions, it’s an overview of the things one should avoid doing. I love photographic mistakes and glitches, which is why I was drawn to this publication, and its chapters are quite hilarious and verbose, including, “When The Cap Is Inadvertently Held Before the Lens, While Making an Exposure,” and “Pictures in Which Perpendicular Objects Lean, or Have the Appearance of Toppling Over.” It even directly articulates some of my favourite accidents in vernacular photographs, particularly “The Shadow of the Operator.”

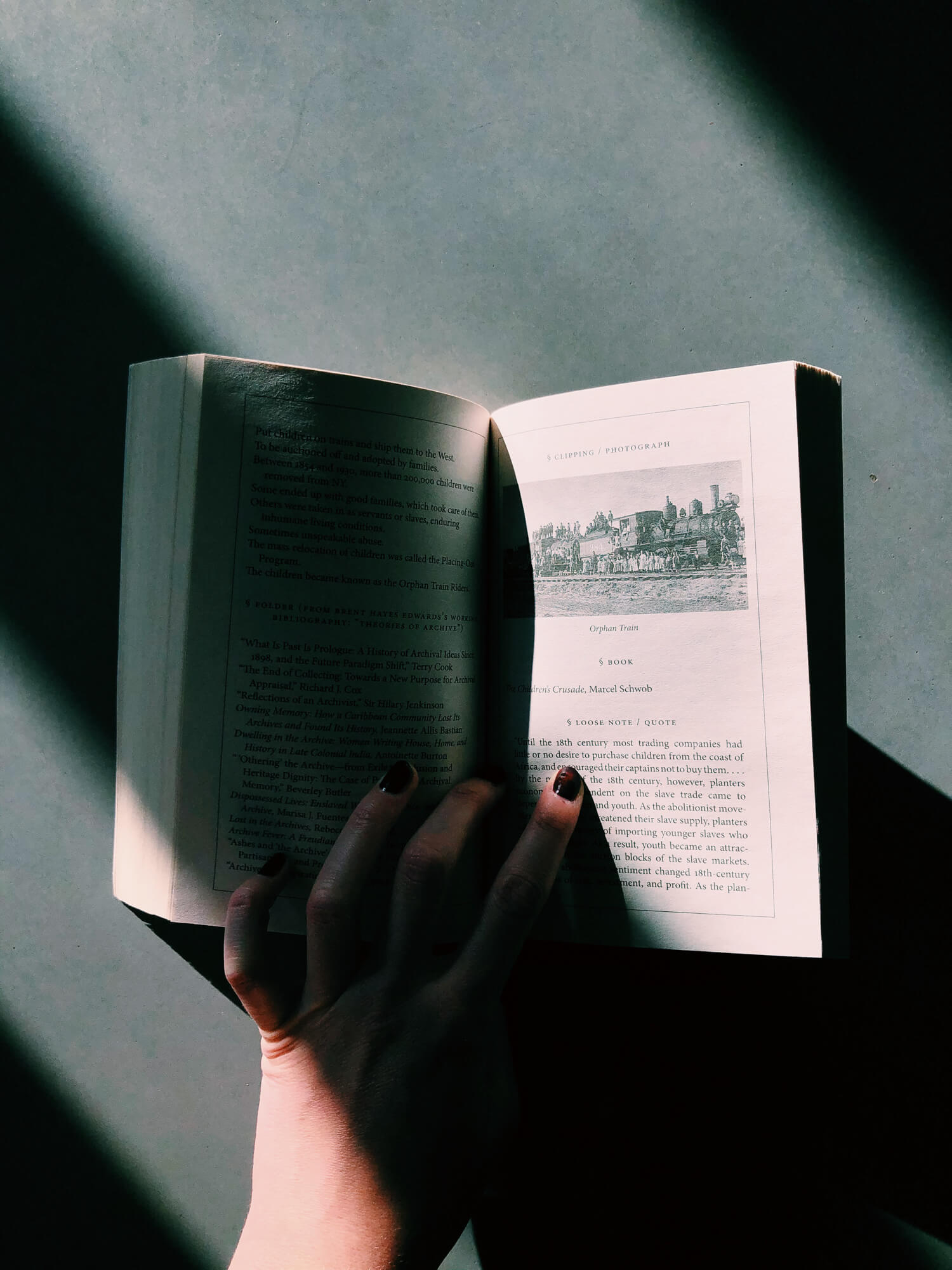

Lost Children Archive – Valeria Luiselli

It’s weird—I remember this book feeling incredibly visual, and when I reopened it to count its photographs, there are only a handful of polaroids sequenced in the appendix of its final pages. Luiselli’s autofiction contains many layers, and its chapters take the form of “boxes” in an archive, carefully compartmentalizing the pieces of an unravelling family as they journey from NYC to southeast Arizona, creating conceptual documentaries on migration. Luiselli constantly questions a writer’s place in telling the stories of others, never quite reaching a perfect moment of resolve, especially within the confines of her archival structure. I love this book because it reminds me of all the times I’ve interviewed documentarians about their work, broaching the tense subject of bearing witness, and how everyone always has their response to this conundrum rehearsed: I stayed there for at least three months. I made prints and gave them to the people I photographed. The individuals in these photos are my friends—I just texted them last week. Cool, bro. Sounds robotically legit. In contrast, Luiselli’s confrontation lays this volatility bare with humility and gorgeous, problematic prose. One of my favourite bits is when she likens reading Kerouac to “an infinite bowl of lukewarm soup.” Eat your hearts out, wanderlust SLRs.

What can I possibly say about Beloved that hasn’t already been said? It isn’t hyperbolic to state that this is the best book I have ever read, and likely the best book on Earth. Anything written by Toni Morrison is completely saturating, and Beloved is a potent exemplar for all of her transgenerational abilities as a narrative conjurer. When I see people reading this book, I suppose I experience the converse of the amygdalic buzz that courses through me when I see dudes earnestly reading Infinite Jest in public, prompting me to slowly back away, avoiding any sudden movements. Instead, I’m the one who becomes the creep in this context, awkwardly leaning forward without blinking, trying to glean what page the reader’s currently consumed with. I could read Beloved every day for the rest of my life and find something new to fixate on each morning.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.