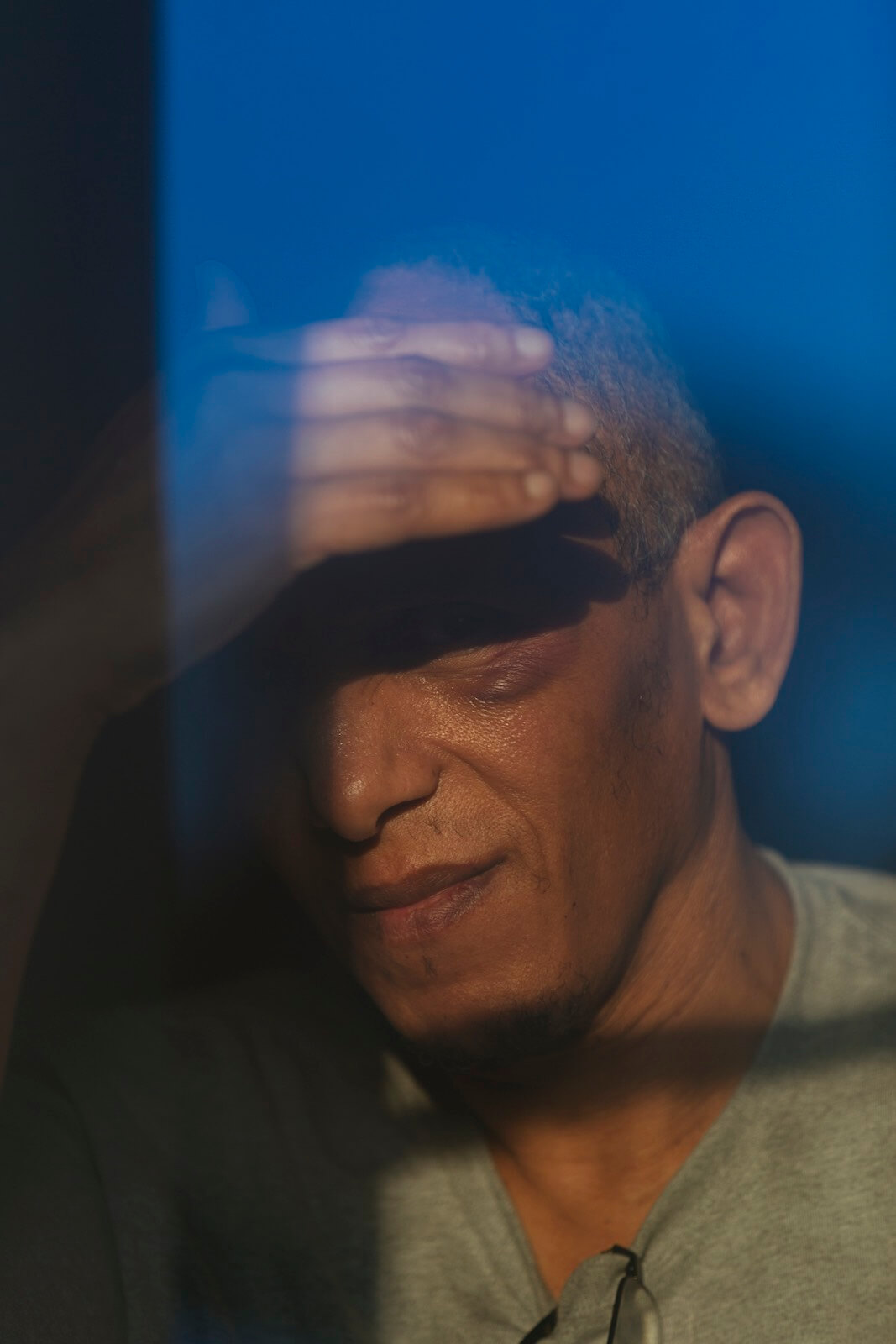

Dawit N.M. on Shane Rocheleau

Dawit N.M. (b. 1996) was born in Ethiopia and moved to America at the age of 7. His experience in Ethiopia led him to have a different perspective on life and also a different level of appreciation for living in America. Countless hours of time spent on the internet developed his interest in film and later photography. His fascination towards community, family, and intrapersonal conflicts leads him to use both mediums to help shed light on truths that are hidden from the world and even the individual.

Shane Rocheleau was born in Falmouth, Massachusetts in 1977. He received his BA in Psychology and English from St. Michael’s College in Vermont, a Post- Baccalaureate Certificate in Fine Art from Maryland Institute College of Art, and his MFA in Photography and Film from Virginia Commonwealth University. He has taught photography as an Assistant Professor of Art at St. Norbert College in Wisconsin, as an Adjunct at numerous institutions, and presently serves as an Adjunct Assistant Professor at VCU.

His first monograph, You Are Masters Of The Fish And Birds And All The Animals, will be published in April, 2018, by Gnomic Book. He currently lives and works in Richmond, Virginia.

left: Shane Rocheleau, right: Dawit N.M., throughout the article.

“In order to be a mentor and an effective one, one must care.” – Maya Angelou

Shane Rocheleau cares a lot.

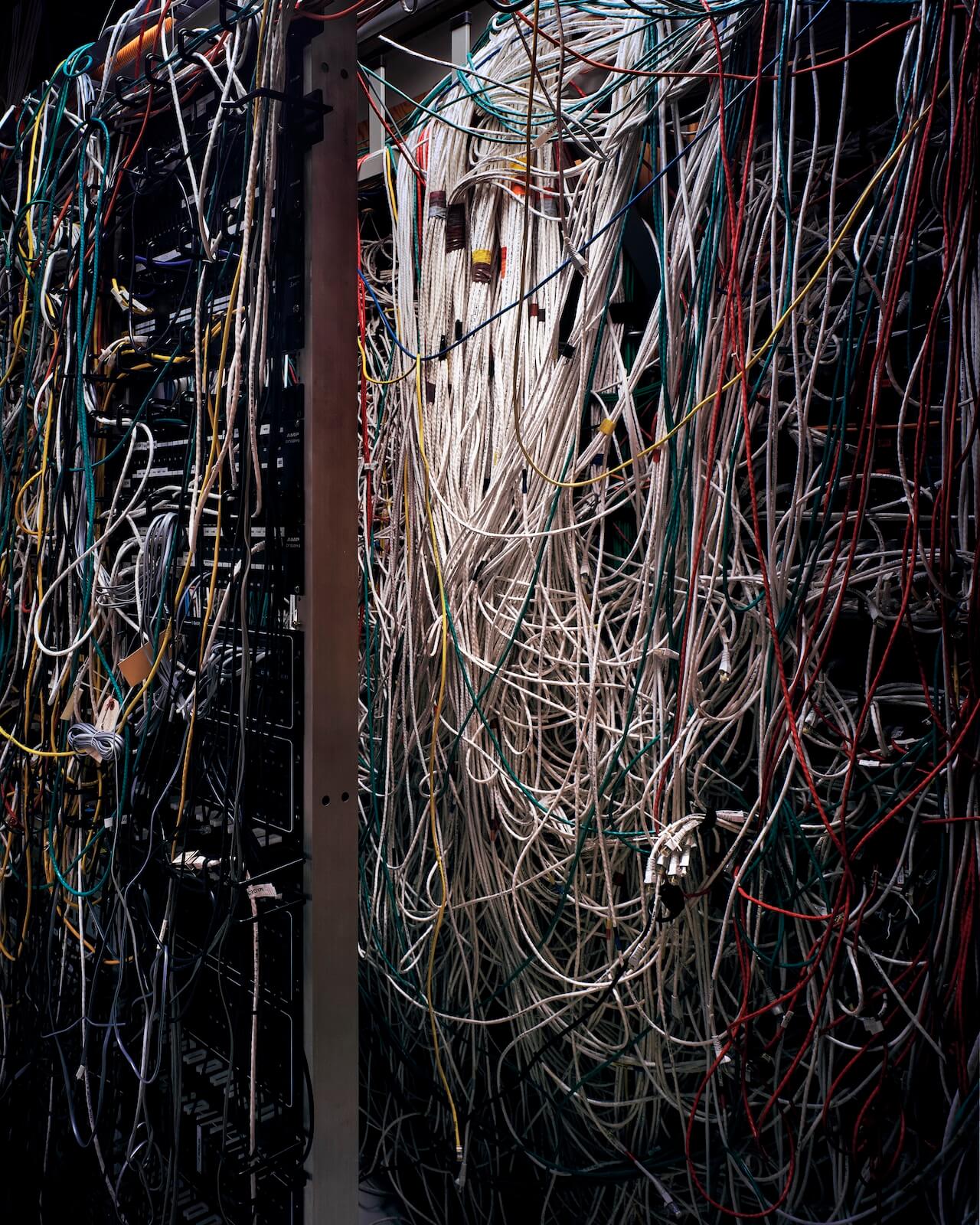

Shane and I crossed paths during my second year in college where I was a student in one of his classes. An analog photographer teaching a tech junkie. I thought it was a strange mix at first, but I soon realized the value of the contrast. In a world where I was used to the fast pace lifestyle fueled by technology, Shane slowed things down for me.

Shane is a person whose words I will carry on and pass down for generations to come. His lectures dug deeper than the realm of photography; he spoke about life, humanity and love. I was able to see the world and the people that inhabit it in a different light through the lessons he taught me.

I remember one day, he told his class that all humans are the same and that the idea of individuality is exploited and distorted so that people fail to realize that we are all the same. I was in awe when I heard this because all of my life, I viewed the world as if it was revolving around me and failed to realize everyone felt the same. After the epiphany, my sense of empathy for others heightened and it started to show in my work.

Shane’s approach to photography was one that I was not familiar with. It was very slow and thoughtful. He took the time to get to know the person. The landscape. He revisited spots different at times of the day to find the best natural lighting situation. When he ultimately takes the photograph, he also takes his time and make sures that the content he has framed not only speaks truthfully, but is conscious, also, of its historical value.

When you listen to Shane critique a piece of work, you can hear the richness of social, political, and art history mixed with the technical aspects of photography. He would look at an image and connect it to a painting that was painted centuries ago and then dive deeper by speaking on the historical significance of the color shirt the man is wearing, paired with the color of the brick walls in the background. He gives you a perspective that most people can’t access not because they don’t know, but because for them it’s happening in their unconscious mind. That level of wisdom inspired me and still inspires me to learn and unlearn a lot of things.

One thing Shane does, that probably irritated some of his students, is his way of answering their questions with questions. Unlike most, Shane uses the maieutic approach, created by Socrates, to help create a conversation with his students, “a form of cooperative argumentative dialogue between individuals.” This not only made the student self-efficient, but also self-critical. Efficient in thinking on their own. Critical in their way of thinking.

His use of the not-so-popular teaching and conversation technique helped me become more aware of my actions and my thoughts. Now I question my actions so much that I’m usually able trace it back to the idea’s origins. Even though our styles of image making is not quite the same, it still has the same intention, or at least I try my best to match his. Being brutally honest is the intention. I first started to pursue this intention when I started making photos of my father.

In 2011, my father suffered a stroke on the left side of his body which would ultimately put him in a wheel chair six years later and yield him from being able to walk. My father and I’s relationship was distant. Even before he got sick, our talks never stepped out the boundaries of school and my career. My father inherited his father skills from his own father, who was also distant. I didn’t blame him for not teaching me other life lessons, but I couldn’t praise him either when I learned it on my own. It wasn’t till Shane assigned us our last assignment for our classroom that I took interest in photographing my father. During these photo sessions, our relationship morphed into a friendship. We were able to talk to each other about anything. We exchanged many words during the photo sessions. As the talks got deeper the photos became more impactful.

My father taught me a great deal about dialogue. Seeing the way he interacted and responded to my questions showed me how valuable it is to humanize and connect with others. Especially now, we are connected more than ever, but losing connection at the same time. Just like how the words my father and I shared changed my view of him, I want that same effect with the images I make. I didn’t realize it then, but looking back Shane’s approach to photography was how I approached photographing my father. The approach not only made for good photographs, but it made for a good relationship. A relationship that I most likely wouldn’t have if it wasn’t for Shane.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.