Gilleam Trapenberg in conversation with Will Matsuda

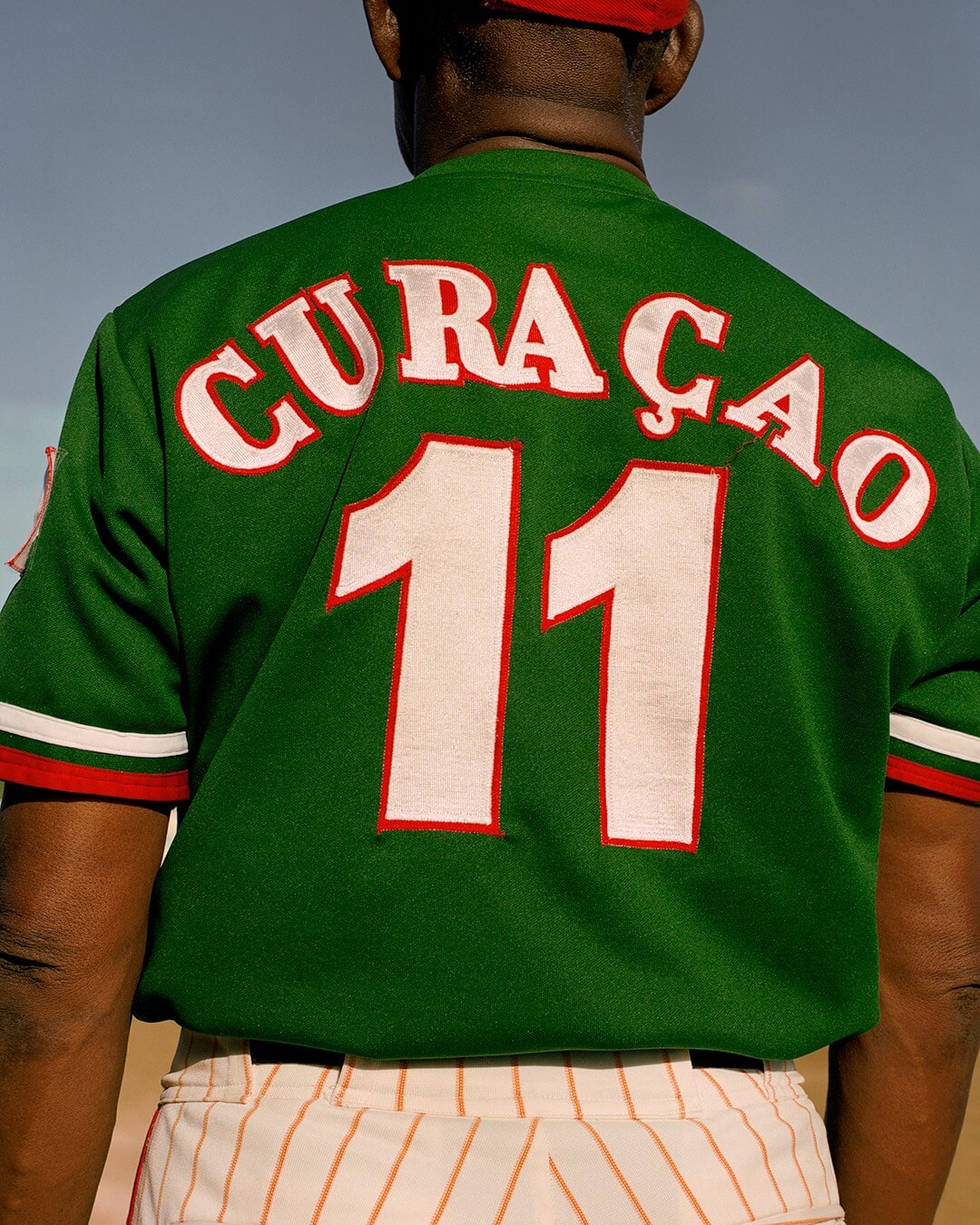

Gilleam Trapenberg (b. 1991) received his BA in Photography from the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. Born in Curaçao, his fascination with themes such as status, representation and westernisation have long played an integral part in his work, as these relevant themes make up the social landscape in Curaçao. He is currently based between Amsterdam and Curaçao.

Will Matsuda is a photographer and writer from Portland, Oregon. His work engages with his family, labor, and the natural world. His images and writing have appeared in The New York Times, NPR, Aperture, The Fader, and Topic, among others. Previously based in Portland and Honolulu, he is an MFA candidate in the Image Text program at Ithaca College.

Will Matsuda: Where are you now – Curaçao or Amsterdam?

Gilleam Trapenberg: I was recently in Curaçao for my mother’s birthday, but now I’m back in Amsterdam where I’m currently living. All my family is still on the island and my personal work is based in the Caribbean so I try to go back as often as possible. Curaçao is part of the Dutch Kingdom, so we have the same Dutch passport. It’s natural that after you finish high school, you move to the Netherlands to continue your studies. You can do the same in Curaçao, but the opportunities are limited, especially if you want to do something in the arts. I moved here when I was 19 to study at the Royal Academy of Art. I lived in The Hague for a bit, and then I moved to Amsterdam last October.

WM: Why did you decide to photograph and examine masculinity in the Caribbean?

GT: I was always in doubt about my own identity. My father is black and my mother is Caucasian. In the Netherlands, people use this word allochtoon to describe me, which basically means “immigrant.” They think I’m Moroccan or Turkish, which might be because of my beard and my complexion. But I always get this comment too: “You can’t be from Curaçao because you’re not black.” In Curaçao, I was always seen as the Dutch guy. I speak Papiamento, the native tongue, without an accent, but I can also speak Dutch very well. I’m in the in-between. Big Papi started off as a documentary project about me informing other people about the Caribbean, and then it turned out to be very autobiographical.

WM: I’m interested in hearing more about that. How is it autobiographical?

GT: I realized this after I published the book and saw the project as a whole. I work analogue, and there are no photo labs in Curaçao. I photograph for three or four months at a time and then I go back the Netherlands and scan and edit. There’s often a six month gap between the moment I take a photo and when I look at it. And when I finally see it, it’s in the dead of winter in Amsterdam sometimes. The images wouldn’t be the same if I was living in Curaçao; I wouldn’t be photographing in this same romanticizing way.

WM: Are you homesick?

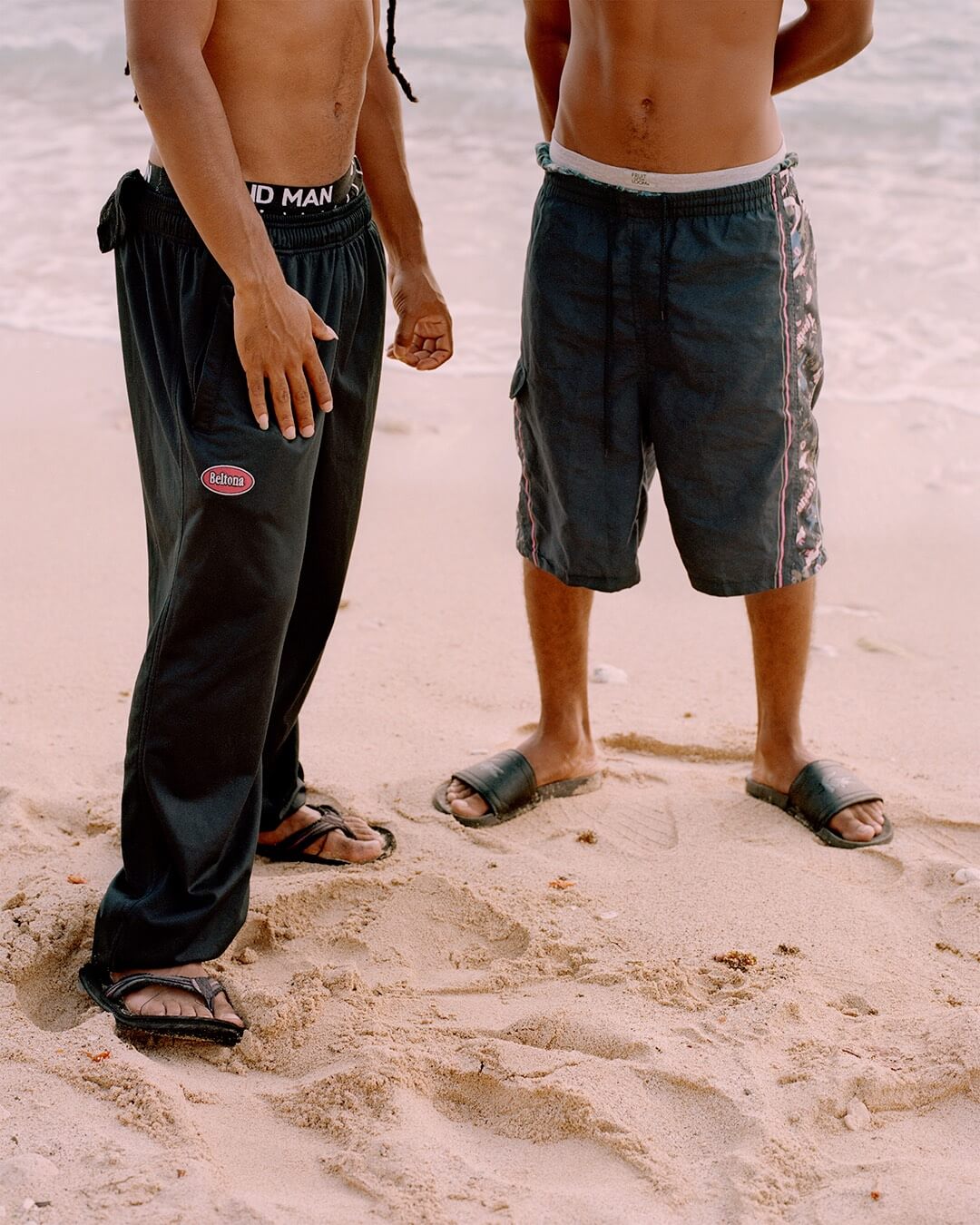

GT: Yes, definitely. But mostly, I’m trying to understand macho culture in my home. In the Netherlands, there is a lot more social control over your actions. Everything happens inside the home. For example, in Curaçao you see lots of guys hanging out in the yard with no shirt, and that’s just normal. It’s not the same in the Netherlands. My mother sees a lot of things as macho, which I don’t. Do you know the Adidas slip-ons? In Curaçao, I used to wear those slippers all the time, but my mother told me that they are associated with thieves. She said, “You’re not wearing those slippers to lunch today.” I mean, they’re just slippers, but it’s connected to the macho man stereotype in Curaçao. I’m interested in things like this and how that came to be. Big Papi was made for people in the Netherlands because I hear the stereotypes they have about my home, especially about black Caribbean men. And it gets more complicated because some people in my own family hold some of these stereotypes.

WM: Do you notice that a colonial gaze persists?

GT: It’s complicated because many of the stereotypes surrounding Curacoan men don’t come from the Netherlands. They are actually shaped by the American media. In Curaçao, a lot of the “macho” men emulate guys like Rick Ross; they have big beards, big chains, and no shirts. That flashiness comes from American culture. The influence of the Dutch is bigger, but it’s more underlying, and not so obvious. I’m examining the stereotypes that the Dutch project onto black men in the Caribbean. I want the images to reflect this discussion and this friction.

WM: Are you trying to reflect this discussion, or subvert it?

GT: There’s the picture of a boat named Viagra. Some men in the series present themselves as super macho. But then there’s other more romantic, tender images of couples hugging, and things like that. I needed both types of images. It’s too easy to do a project about masculinity if the work only portrays a one-sided view. I use the stereotype to talk about the other topics. Every time I meet someone new and I tell them I’m from Curaçao they say, “Wow, your Dutch is so good! And “how come you aren’t black?” I have that conversation so often. While starting the project I was interested in presenting an informative view of the Caribbean. But then it became much more interesting to start a discussion around the stereotypes surrounding masculinity. I’m reading this amazing book called Last Resorts as research for new work and it talks a lot about neo-colonialism and westernization happening in the Caribbean through tourism. These are themes that are also part of Big Papi. In the 90s, when all these hotels started popping up, the beaches started to get more privatized. Today, as a local, you can’t even get onto the beach without paying a fee.

WM: What’s your process like when you’re shooting in the Caribbean?

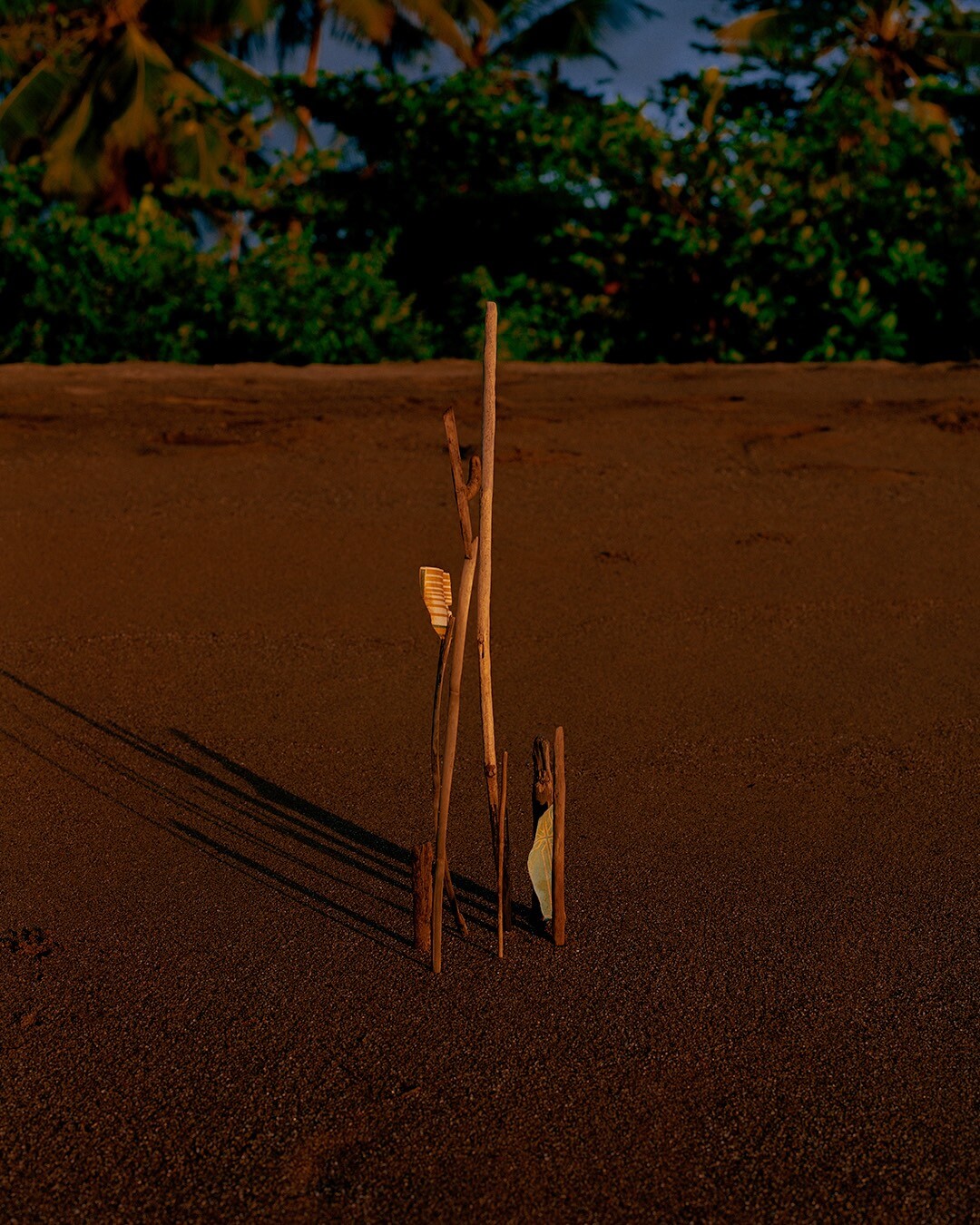

GT: Years ago, I started off walking around and shooting with a snapshot camera—palm trees, beaches, and that type of stuff. All very banal things. I’m not an essayist; I’m more of a hunter. I know what I’m looking for before I head out to shoot. That’s mainly due to the fact that for most of the year I am not in the place where I am making this work. I do lots of planning while I’m away from the island. I daydream about the images I could make. I make keywords for myself. I write all these images down in my notebook. For example, the still life with the sticks on the beach—I dreamt of that image for years. I wanted to make it so bad. Some of the portraits are more planned, I knew I wanted couples as the male female dynamic is something I’m very interested in. There’s this photo of a man with a hat hugging his girlfriend. He’s an employee at my father’s company in St. Martin. My father told me he has seven children with different women. I wanted to meet him since I was researching the stereotype. However, I quickly realized that it would only add to the stereotype if I photographed him with all his ex-girlfriends.

WM: So, what’s next? Have you moved on from Big Papi since the book came out?

GT: While I was interning with Stefan Ruiz in 2015, we went out to lunch with Dana Lixenberg one day and she was talking about her Imperial Courts project. She had been worked on it for 23 years! That stuck with me. When I finished the book, I was thinking about how I’d barely scratched the surface. There’s so much more to do. I’m not actually finished with Big Papi. I want to dissect the themes in the project even further, as their own projects. I’ve been talking about Big Papi for so long.

WM: Yes, you’re probably ready to talk about something else.

GT: Yes, but I am also glad to talk about it because I feel that the Caribbean has to be represented by people from the Caribbean. Ask anyone to name a few Caribbean photographers. I don’t think they could name more than two. There’s Kevin Osepa, who is making amazing work about religion, the African diaspora, and family. But I don’t know anyone else making work about the Caribbean, from there or not. I feel that this is something I have to do.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.