Irina Rozovsky in conversation with Jack Deese

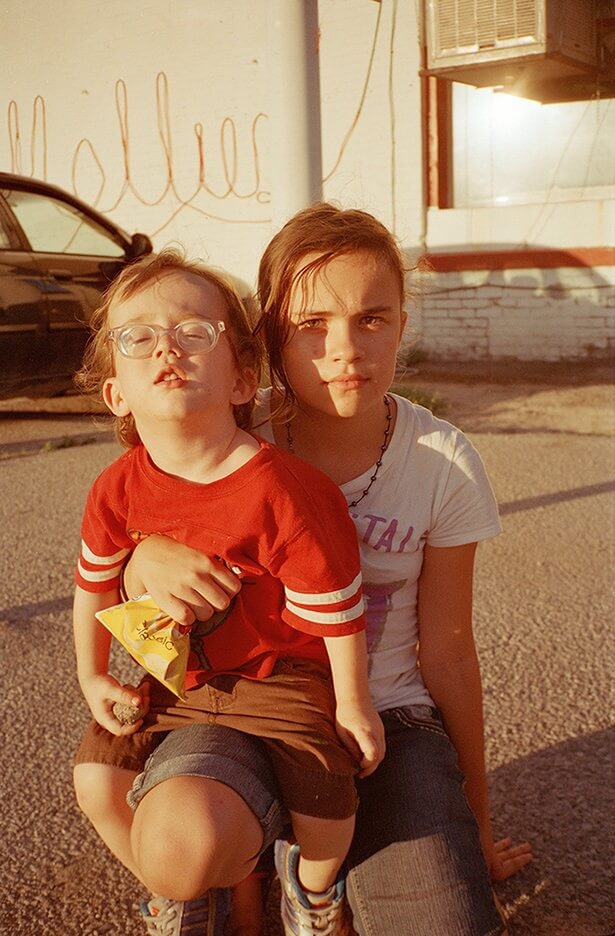

Irina Rozovsky (born in Moscow, raised in the US) has published two monographs, One to Nothing (2011) and Island in my Mind (2015). Her work is exhibited internationally and is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Irina’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, New York Times Magazine, Harpers, and Vice. She lives and works in Athens, Georgia where she and her husband Mark Steinmetz run the photography project space The Humid.

Jack Deese (b.1986) is an artist and writer born and based in small-town Georgia. He received a BFA in Photography from the University of Georgia, and an MFA in Photography from Georgia State University. His artwork has been exhibited nationally, and his writing has been featured in Burnaway and Yield Magazine. The majority of his work is made close to home, or on the road looking for something good to eat. He currently teaches at The University of Tennessee Chattanooga.

Jack Deese: You received a BA in French and Spanish literature, what spurred the jump to photography for your MFA? Was that always the plan?

Irina Rozovsky: There was never a plan, just a gradual realisation that photography was what I needed and wanted to do, against all odds. I had never formally studied it, so I threw myself into an MFA. I had a few interesting jobs after college that used my Russian, Spanish, and French but I always felt like an operator relaying across cultural divides a message that I could decode, but that didn’t belong to me. The part of the brain where languages live is a very fertile place for me, but photography was a truer form of communication–the most expressive means I knew by which to actually say something.

JD: Thinking of language, I noticed that in your earlier projects, such as This Russia, the photos all had titles, and now the majority of your work is untitled. What is the photo title process like for you, and why the shift to untitled images?

IR: The somewhat abrupt shift from individually titled photographs to the murky territory of “Untitled (from Project Name)” began when I started to work on book-oriented projects rooted in singular places. My earlier method eschewed geography and gathered photos made all over—a placeless spread. Each image had to define and proclaim itself. When my work started to become more specifically connected to place, the name of the project/book became the framework that freed each photograph from needing definition. I felt I was able to get my point across in the naming of the project. I like the namelessness of “untitled” and the quality of belonging to suggested by the “(from…)”

JD: In regards to your work being situated as documentary, you’ve previously spoken about your photographs made in Israel for One to Nothing as having “no obvious facts.” I was hoping you could expand on that idea, and if you still feel that’s true.

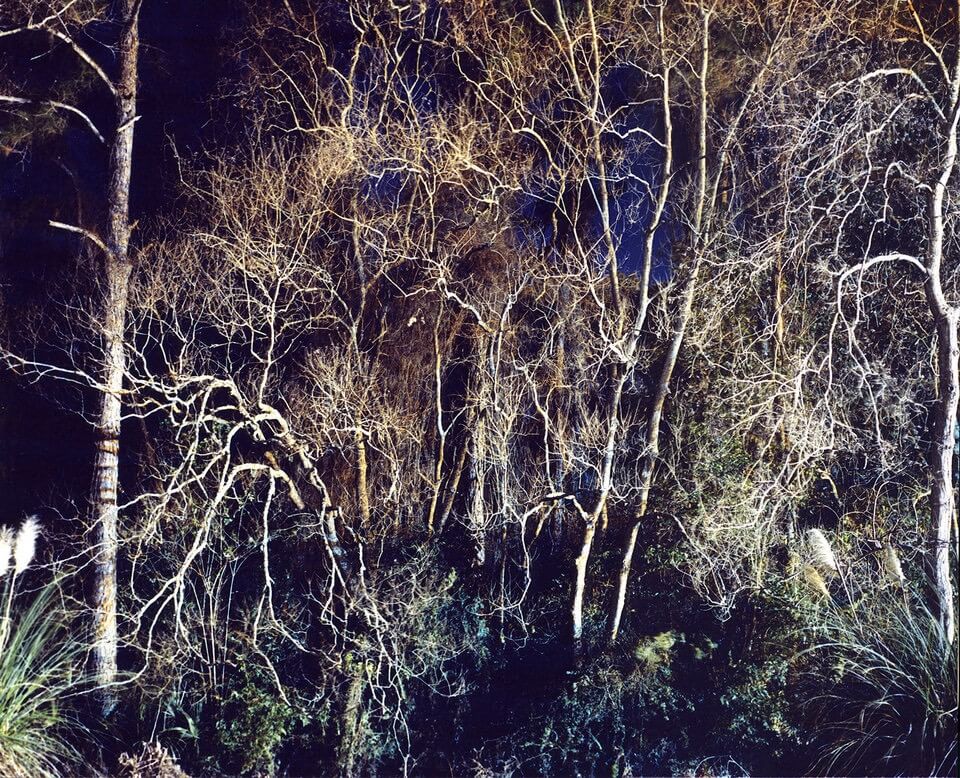

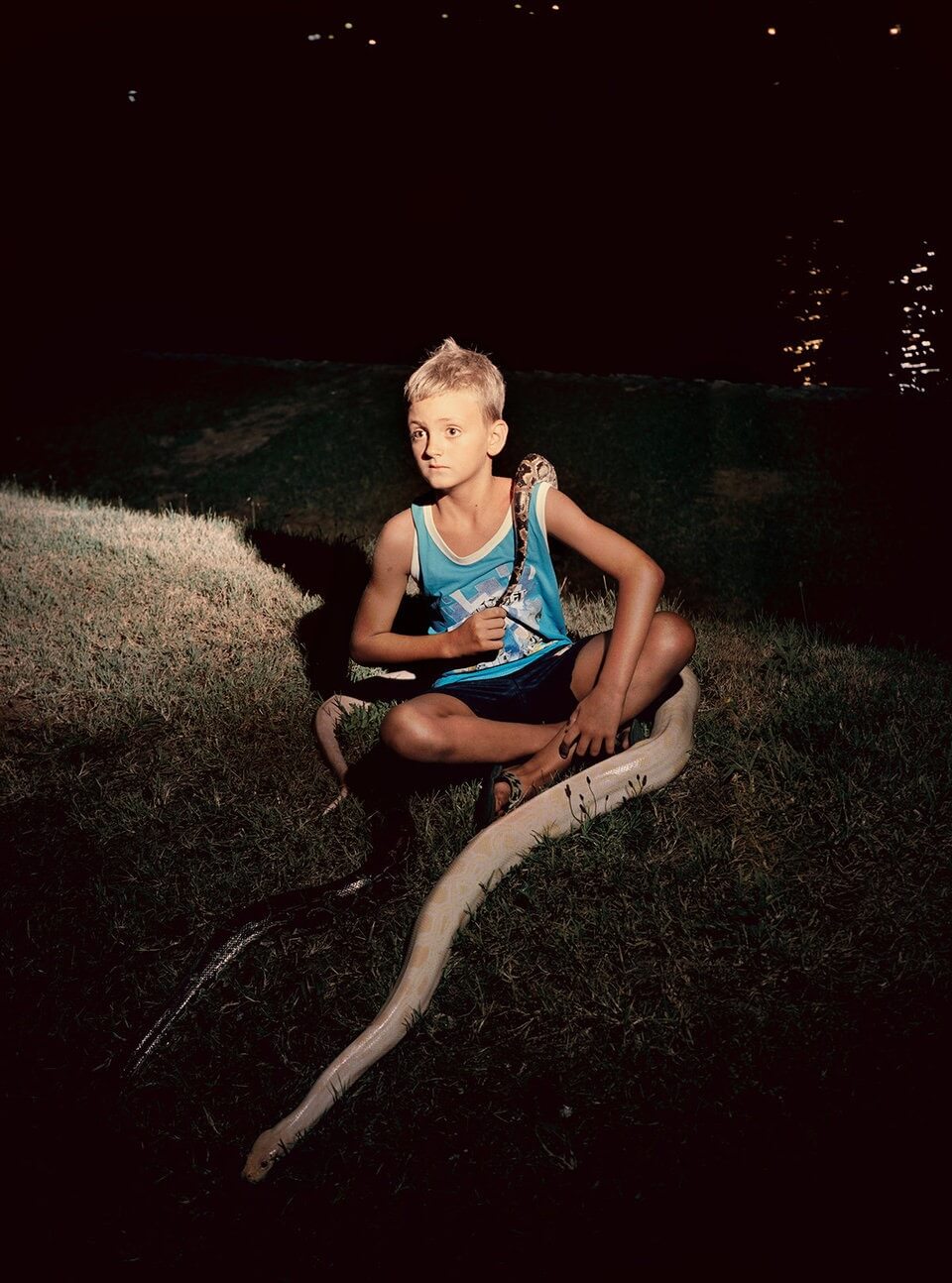

IR: My commitment to photographs with little obvious fact but an atmosphere of truthfulness grows ever stronger. I want to fold the experience of life and the reality of place into a photograph and make something new of the ingredients. Of course, facts are important, they shape everything in our lives. But for me pictures deal with the “after the fact.” I like nothing more than a well-told story, complete with hyperbole, dramatic effect, humor, climax, etc. (except, please, no fantasy) and it’s the feeling and energy of that storytelling that I want to depict.

JD: Your various bodies of work are made in locales spread far and wide, but share a sensibility about them. How much overlap is there for you in your process with each new body of work? Is your editing and shaping of the work happening simultaneously as you make the photographs, or do you leave those decisions until all the photographs are made?

IR: Until recently there was a lot of overlap between bodies of work. One project rubbed off on and led into the next. Although the places where I found myself making pictures were far apart, they felt intrinsically linked. Do I envision the body while in the process of shooting? Yes and no. I don’t have the end clearly in sight but there is always a direction. It’s like when you set out towards a destination in the car and become blind to the road.

IR: Behind the wheel you stop being conscious of the actual driving, your mind drifts, but then you’ve suddenly arrived. That’s what shooting towards a nebulous end goal feels like for me—it’s happening in another kind of consciousness. I think photographers make a lot of decisions and edits constantly, without being aware of them. I like to work in a mental space where the decisions sort of make themselves: I’m steeping in a haze but somehow arrive at the whole. It’s not always so smooth. More recently, since becoming a mother and moving to Georgia, I’ve had no opportunity to get lost in distant lands and my way of making photos has come entirely undone. I’ve turned to photographing in a way that’s difficult and awkward to understand. The camera is not so much the third eye that it used to be but a conniving provocateur. I make hundreds of photos of essentially the same thing, like a basketball player practicing a layup. It feels balletic in its individual movements but the entirety is still unknown.

JD: With these hundreds of photos you’re making, or with your work previously, how do you determine what to keep and what to let go?

IR: Sometimes, in editing, a photo will jump out from a contact sheet and announce, like a little prophet, that it’s the one. It’s hard to explain the chemistry of these rare and coveted encounters—it’s a picture that’s clearer, stronger, more alive, more right in its wrongness, more serendipitous and more surprising than what I was expecting or thought I could do. This image goes on to shape the rest of the project and demand that the other pictures keep up.

IR: More often, there is endless deliberation and careful weighing. A photo might surface slowly, hesitantly but stay the race. The rest are tucked away and live on meekly as “studies.” Recently, with digital images, the process is soupier. There are many nearly identical images, and it’s harder to choose a single winner. While outtakes in negative form sleep soundly in black boxes until I have reason to look back at older work with new purpose in mind, digital images are often prey to my purge urge. I like to delete the images that are almost good.

JD: Do you feel a certain preciousness about particular photographs? For instance, if they are of a specific subject? I’m thinking about you making an image while working in a particular region or country, but that doesn’t mesh with your other images. Do those images have a home, or are they just tucked away?

IR: At the moment I feel a preciousness towards photos of my daughter and old family albums, but I hope not to have a sentimental relationship to my work. I would protect an important image from damage with an animal instinct, but when boxes of negatives or hard drives or old prints have been under threat, there’s a strange, slight relief on the other side of the sinking feeling of loss. Like hell, I’ll just start again from zero. And to touch on whether images have a home—a good photo will eventually find a home that hasn’t been built yet. Many times, a picture might be a message for the future.

JD: You have taught photography for some years, outside of technique, what do you feel are important elements for your students to take away from your class?

IR: How to be their biggest, best selves. How to listen to their intuition and stay open to chance and work with errors.

JD: What have you recently read, listened to, or seen, that has moved you in some way?

IR: Lately, it’s been all baby lambs and baby cows — all the baby farm animals folding into mostly irritating bedtime stories. I am desperate for good kid books; please advise! Outside of that, I have just enough brain power for short stories and, still locating myself here in the south, am going straight to its legends. I just read The Jockey by Carson McCullers and Faulkner’s That Evening Sun. Both so focused, so vivid, minimal yet full–nothing really happens, drama is only hinted at, and you know it erupts ten minutes after the story ends. I like that kind of understatement very much.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.