Jason Hanasik on Jo Ann Walters

Jason Hanasik is a filmmaker, artist, curator, and journalist. His work has appeared in The Guardian, at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, in The Los Angeles Times, in the academic journal Critical Military Studies, at various international film festivals and in solo and group visual art exhibitions around the world. His monograph, “I slowly watched him disappear” is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art NYC, Stanford University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Hanasik has a Masters of Journalism from UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism, a Master of Fine Arts from California College of the Arts and a Bachelor of Fine Arts Summa Cum Laude from the State University of New York at Purchase. He is currently a resident at SFFILM’s FilmHouse where he is editing new films for The Guardian and the BBC.

Jo Ann Walters is an artist working in the field of photography. Upon seeing her work in the mid-1980’s, William Eggleston described her as one of the few independently original photographers working in color today. Her photographs can be found in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, St Louis Art Museum, Portland Museum, Peabody Essex Museum of Art, Library of Congress, Bibliotheque Nationale and the Center for Fine Photography, Bombay among others. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Ferguson Award for outstanding portraiture, the Kittredge Fund Award as well as the Peter S. Reed Foundation Fellowship awarded to distinguished writers, choreographers, filmmakers and visual artists in their fields. She was nominated for Anonymous was a Woman and the John Guttman Fellowship from the San Francisco Foundation. She has been on the faculties of Yale University School of Art, Rhode Island School of Design and is currently a professor in photography at Purchase College, The State University of New York.

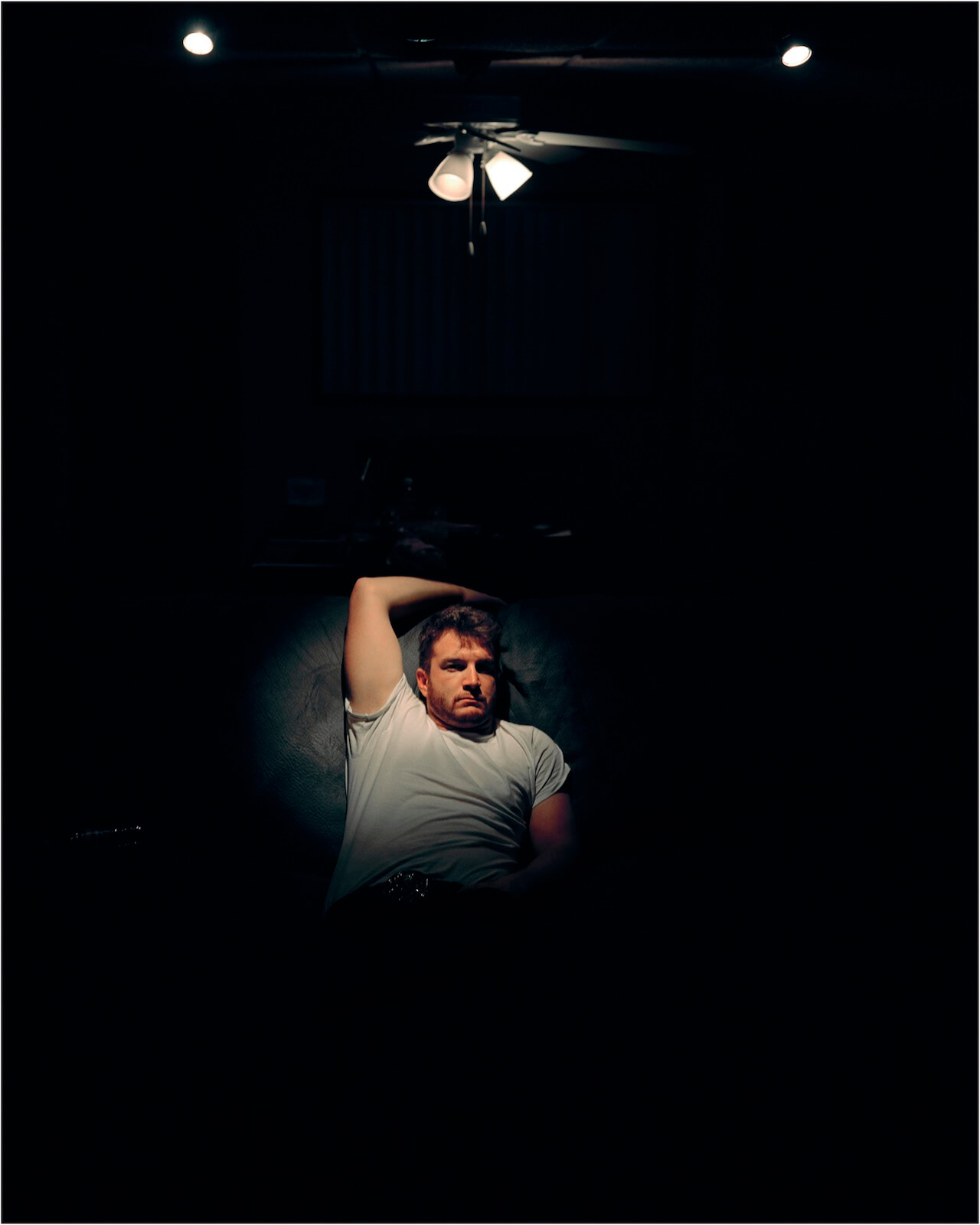

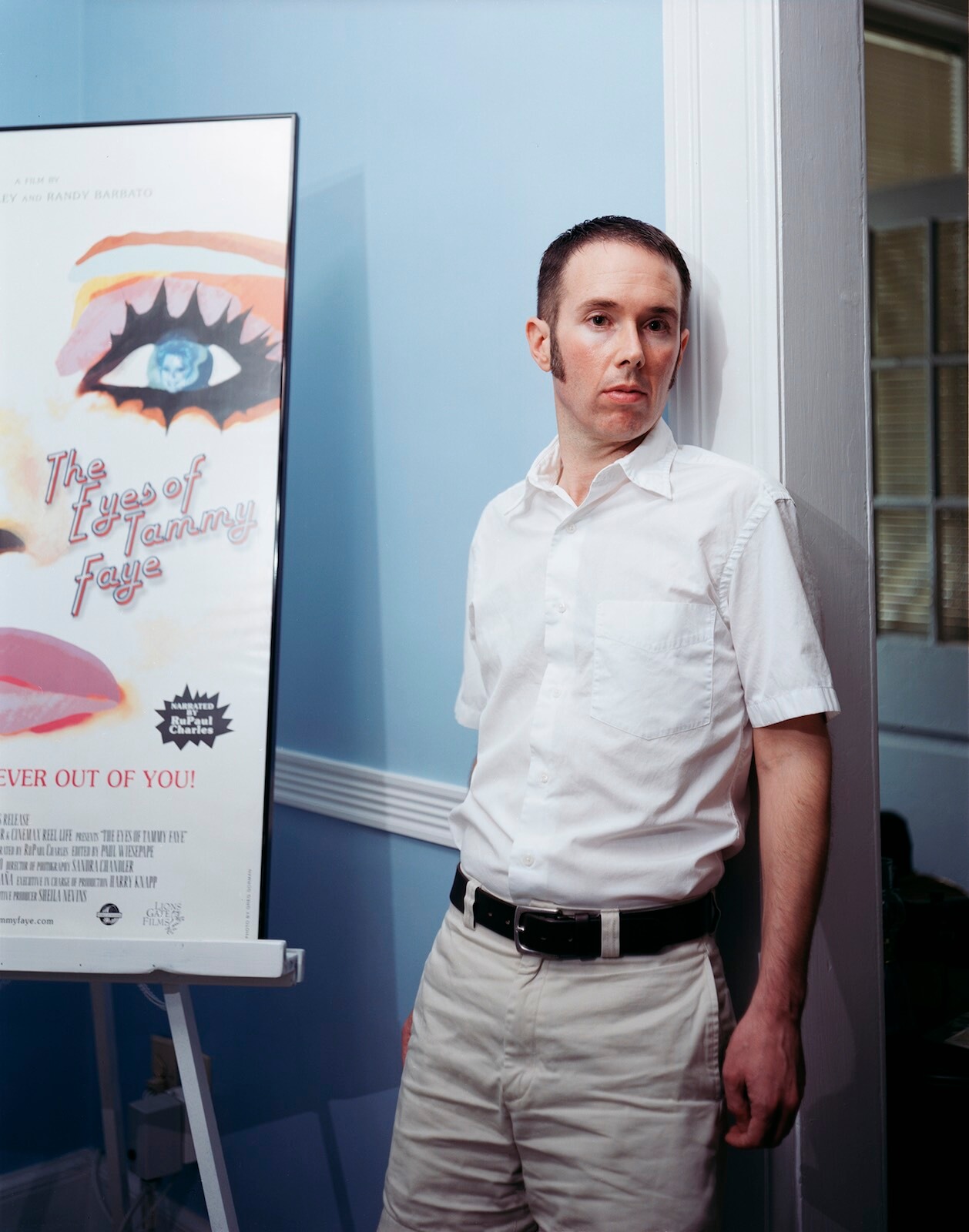

1: Jo Ann Walters, 2: Jason Hanasik, throughout the article

The first time I met Jo Ann Walters she asked me to stand up in a design hall full of prospective students and sing a song. She said it could be any song I wanted just as long as I stood up in the middle of the hall and sang. At the time, I was applying for admission into the Visual Art department at the State University of New York at Purchase. Jo Ann was the head of the program and the designated reviewer for that day. The request came after she had finished reviewing my portfolio. In my nervous desire to impress her and be accepted into the program, I revealed that I had studied voice all throughout high school and with a twinkle in her eye and a cool poker face, she said, “great, show me what you learned.”

Shaking a bit —as I was more of a choral singer than a soloist— I stood up and started singing softly. Jo Ann smiled and I sang a little louder. The design hall went quiet —probably out of the queerness of the scene— and then, as I barely hit the high note, they started clapping. Blushing, I quickly finished the song. Jo Ann said, “Looking forward to working with you in the fall, Jason.”

Six months later when I arrived at Purchase and was registering for classes, Jo Ann appeared behind the table I was sent to to choose my fall classes. When we arrived at choosing my electives for the semester, she invited me to join her Special Projects Field Trips class. I accepted the invitation. On the first day, I quickly realized that everyone else in the class were graduating seniors and a few selected juniors. A mix of honor and terror flashed through me as I found my seat and introduced myself. From that semester on, I had at least one to two classes with her each semester.

Jo Ann Walters is quirky, curious, capricious, and deeply empathetic. She’s completely unorthodox in the classroom and represents everything I love about the expansiveness of an art school education.

When I matriculated at Purchase, I was just coming out as a gay man, incredibly intimidated by the images the junior and seniors were making in the Special Projects class and was consistently failing to make anything that warranted my spot in the advanced class Jo Ann had admitted me into. I was a mess and was also going through a deep sense of culture shock. As the semester drew to a close, I remember throwing the adult equivalent of a temper tantrum at ABC Carpet in Manhattan. It wasn’t my best moment and Jo Ann could tell what was actually in operation so she took me aside and said to reconnect with my family and friends in Virginia over the holiday break, make some pictures and come back rested and ready to work.

During that holiday break, a grand aunt died and I ended up in Florida surrounded by extended family in grief. After asking them if I could make their picture, I started photographing my family and something clicked: the images came easily, naturally, and there was a heat to them. I brought those images back to Jo Ann and my classmates and we began to tease out and develop a language around why these new images worked and what that may mean for me as a maker.

A year after working with Jo Ann, I finally pulled open a book with her work in it. I almost started crying as I flipped through the world she was imaging. She was making the kind of work—not the exact but in the same lineage— that I was seeing in my mind’s eye and I wanted to make but couldn’t.

Jo Ann’s work dances. It’s formally rigorous and inventive. Her pictures are not self conscious or uptight. The individuals who populate her pictures are like the people I grew up with and around and rather than depicting them as oddities to be consumed or looked down upon with pity, Jo Ann brings us —often mid action— into the beauty of their suburban choreography. Children are upside down on handrails and right side up. A young woman is in the back seat of a car crimping her eyelashes. We’re with a family as they lounge about on backyard swing sets or on the edge of an unmarked perimeter guarded by a pack of dogs performing what might be a modern dance piece. In one —almost mythic image— a young girl is wearing what may be her mother’s wedding dress. It pools around her feet while the glow of the afternoon light catches an expression which is far beyond her few years. It’s no wonder that in the mid 80s, Eggleston said Jo Ann was one of the few independently original photographers working in color today.

By the time my senior year at Purchase rolled around, there was no doubt in my mind that she was a mentor and a guide. What propelled her from a great teacher to a goddess —in my mind— was that her wisdom didn’t stop at making pictures or thinking about color. When we saw a solo show at a major museum in NYC by a photographer who was only five to six years older than most of the class, she asked us about the careers we wanted. I responded rather flippantly and she leaned in and replied, “Don’t be a flash in the pan, Jason. It’s generally never good for the work. Build a career that’s a beautiful, slow burn.”

Upon graduation, I attempted to do just that. I moved back to Virginia and expanded the ideas I had just started to tease out in my undergraduate thesis. A few months later, I received a call from a curator at a Chelsea gallery in NYC asking if I’d like to be in a group show. One of the other members already in the show was Jo Ann. During the run of the show Vince Aletti reviewed the exhibition and mentioned our names in the same sentence. It continues to be one of the high points in my still photographic career.

For about five years after I received my undergraduate degree, Jo Ann and I would send emails back and forth and she wrote recommendation letters for my graduate school applications. I even tried to get a two person show of our work together for a gallery in Virginia but sadly, the show fell through at the last moment. Mostly though, I thought about how her work danced between documentary and the still, considered portrait. How her photographs were both of the person being depicted and something that felt systemic and would repeat across generations until the end of time.

Shortly after starting graduate school, my advisor and future mentor, the late Larry Sultan said to me, “A good photograph is like a balloon on a string that is lightly nailed to the floor. The balloon has the flexibility to move and float around as the winds change but it is firmly rooted to some kind of foundation.”

Jo Ann’s images are like that metaphor for me. After seeing a few, I’m fully immersed in the world she’s depicting/creating but what they mean isn’t one thing or another. They’re enigmatic. Her images are not timeless images but they are not caught in the surface questions of a specific time period either. Instead, I think her images investigate the dilemmas faced within certain socioeconomic classes —particularly the joy and challenges women face inside of those economic milieus. I never really fancied or understood landscapes when I was studying with Jo Ann but looking at her landscapes now I see, like her portraits, the land she’s photographing are often the abused and forgotten stretches of the American midwest. You can see Jo Ann’s influence in most of my undergrad work but where, I think, our images join for a curious duet is in the work I was making in graduate school. While I was studying with Larry Sultan —learning how to read images and develop language around the conceptual inquiries in my work— I was still thinking about and just starting to digest what Jo Ann had taught me in undergrad. I remember thinking when I printed “Steven (turn)” that my pictures were finally starting to wiggle free and dance like her’s.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.