Ricardo Nagaoka in conversation with Amy Touchette

Ricardo Nagaoka (b. 1993) is a Japanese-Latino photographer, born and raised in Paraguay, and a grandson of post-war Japanese immigrants. He immigrated to Canada with his family in his teenage years, and eventually landed in the U.S where he currently resides. Ricardo studied at the Rhode Island School of Design (BFA Photography) and his work has been recognized by Magenta’s Flash Forward, American Photography, and Latin American Fotografía. Drawing from his own experiences as an outsider, his work seeks to explore our constructs and ideas of home, heritage, and selfhood in an increasingly pluralized world.

Amy Touchette is a fine art photographer based in Brooklyn, New York, who specializes in street portraits. Trained at the International Center of Photography, she began her artistic career as a writer and painter, earning a BA in Literature and Studio Art and an MA in Literature. Touchette’s first monograph, Shoot the Arrow: A Portrait of The World Famous *BOB*, was published by Un-Gyve Press (Boston, 2013). She is represented by ClampArt in New York City.

Amy Touchette: One of my favorite photography teachers, Ellen Binder Dubner, used to say “What about your project is about you?” as a way of helping us recognize and evolve our own personal vision. She was trying to impart that the topics we pursue are—or should be—an extension of ourselves, a conscious or unconscious drive to continue our path, to find answers or expand in some way what we’ve experienced so far. Assuming you subscribe to this point of view, how are you, personally, reflected in your series Eden Within Eden?

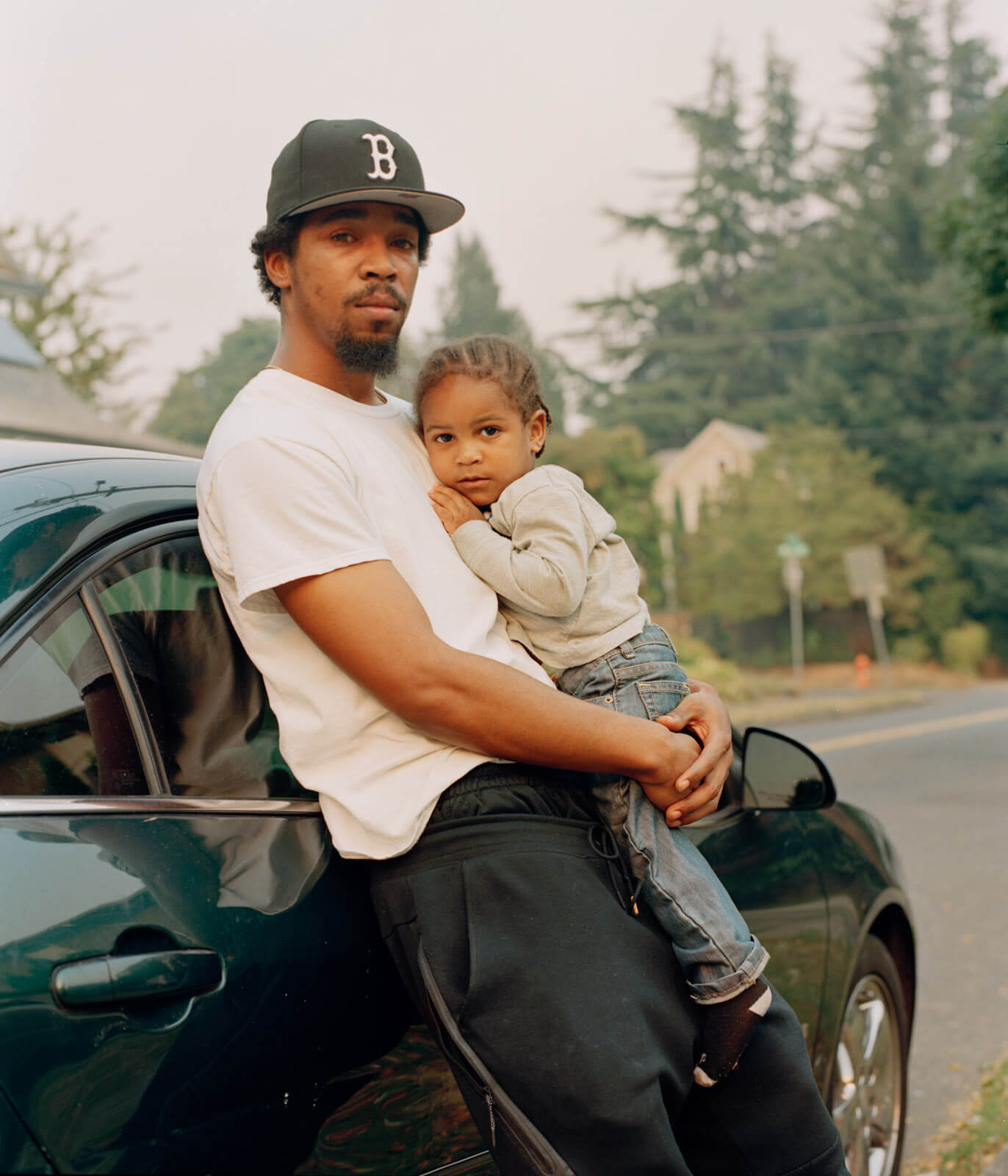

Ricardo Nagaoka: I am definitely part of this school of thought as it was a huge part of my education in photography. If I can’t connect with the images I am making, I feel as if I am veering away from who I am as an artist and photographer. We each have our own unique worldviews which we construct through our lived experiences, and I am a huge believer that developing a voice is about manifesting that individuality. I am a Japanese person who was born and raised in Paraguay, where I was quick to learn what it meant to be a minority in a largely homogenous country. Our family immigrated to Canada when I was 12 which was a huge shift for our all of us, being children and grandchildren of immigrants. We were suddenly placed in the same position my grandparents were in 40 years ago, and with it came all of the experiences of sowing new seeds in a foreign land. Growing up as an outsider, I never really felt at home anywhere. I have questioned what that means in the pluralistic society we live in now, as this idea of home, both physical and psychological, has always been fractured in my psyche. Eden Within Eden is a story of home, its conception, and its untimely erosion. Even though what I experienced is quite different from that of the communities in North Portland, Oregon, I empathize with the emotions that come with the increasingly fluid nature of what we determine as being a home. This body of work has definitely challenged my agency as a photographer, being a total outsider documenting a population that has been through so much pain and deceit. And even though I see my points of connection, I am always aware that this is not my story, but one I feel that is important and to share with a greater audience.

AT: Yes, in The New York Times Lens piece about Eden Within Eden you said, “I’m taking the photos, but it is, of course, their story to tell.” How do you walk that fine line? That seems to be an art in and of itself: to tell their story knowing you have a personal connection to it and still be making decisions as a photographer that impact its expression. Do you select the photographs that make up this series, or are your subjects involved in that part of the process? What is your relationship like with this community and how are you working together to tell help them their story?

RN: It’s been a challenge for sure. As I had mentioned, I connect with the neighborhood and the people through their story and its relation to my own, yet I do not have any familial or personal ties as I’ve had in other projects. The work will eventually culminate in a book, where I am working towards having every written component be a voice from the community, not mine, along with archival images of the community that I have been finding through a local librarian from the neighborhood. I have met certain people from the community who have been incredibly helpful in pushing this project forward who I would also like to be involved in the editing process. The collaboration will happen through this interwoven web of image and text, as it would be the only way that I would feel comfortable publishing this body of work as a final product. In the end, it’s all about making the story resonate with others outside of this community, to further our understanding of the complexities of this subject matter.

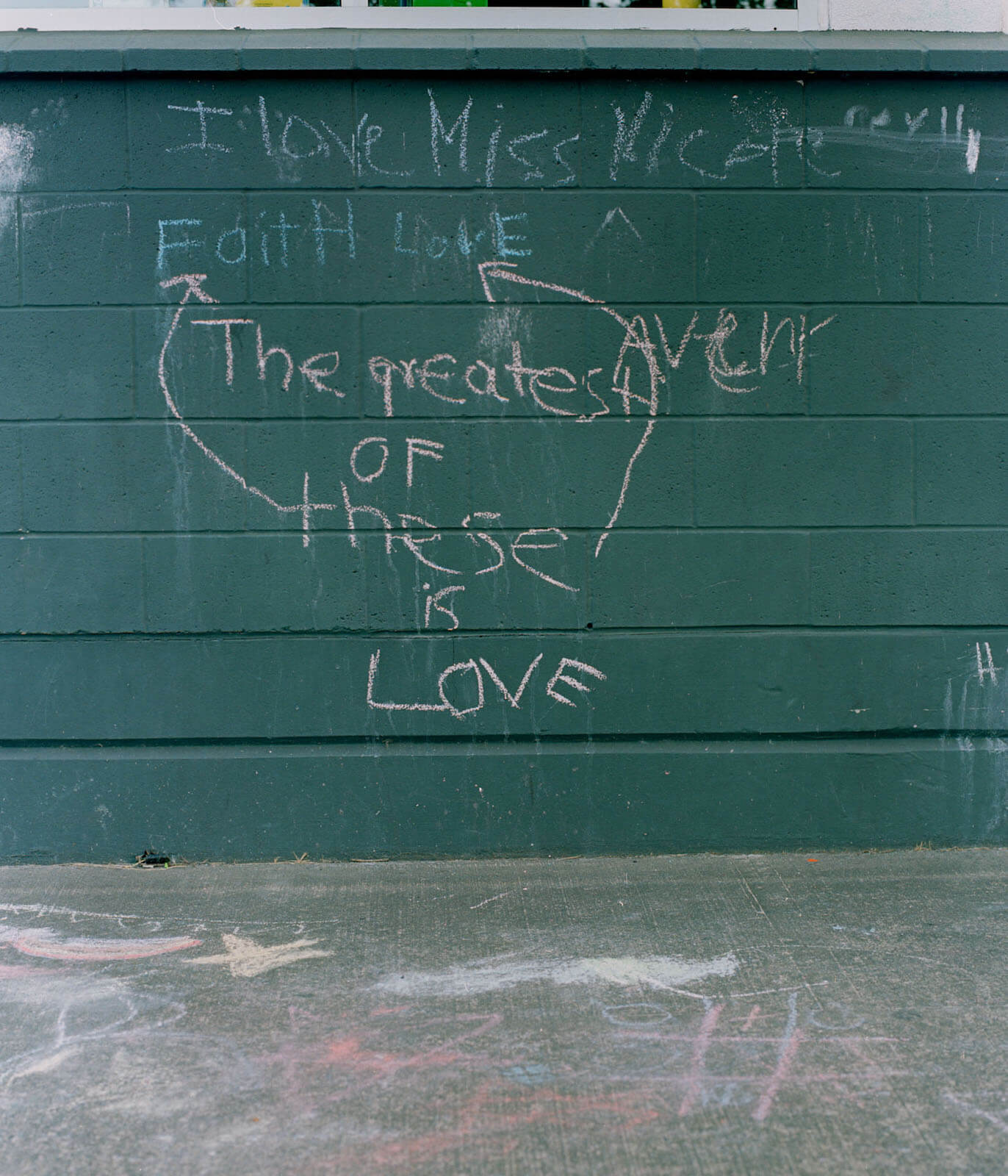

AT: Your sensitivity to your subject matter is definitely palpable. Eden Within Eden contains about as many portraits as it does people-less photos, images of objects, scenes, and landscapes that also help tell the story of this community. In this way I see you interject your voice in their story perhaps even more strongly than in the portrait images. How do you decide which photographs of this kind to make and include? Did you intend to incorporate people-less images from the start?

RN: I have always been interested in the poetic capacity of images, especially when they are seen in sequence. Since I had envisioned this project to be a book from the very beginning, which has been informing a lot of my editing and shooting decision-making, you really get the freedom to have these quieter pictures included in your edit. I often find these commas to be really exciting, because in this repose you have the time to reflect on what you have seen, what you might see, and within all of this you begin to see meaning in objects, scenes, or landscapes that you might have missed if you just saw them individually. In terms of deciding what draws me to make a certain picture, that is mostly gut instinct. Sometimes I am looking for a certain image, but I like to be surprised by the photographic process, especially when at the time I am unsure if a picture will work or not.

AT: Selecting and sequencing one’s own images is difficult for a lot of photographers, emerging and seasoned alike. Your talk about commas as a metaphor for pause makes me think you’ve developed a system for tackling this often puzzling part of the process. What have you learned about sequencing? And how do go about selecting and sequencing images in practical terms? Do you work on your computer? Print out images? Explain how it works for you.

RN: This past year I’ve been looking at quite a lot of photo books, trying to reverse engineer the photographer’s editorial decisions as much as one can. As of now, it’s hard to even verbalize what exactly I have learned about the process. If anything I’ve realized how much of it is intuitive decision-making, letting the images guide you, which was reinforced when I listened to an interview with Jason Fulford who reiterated the same sentiments. I just follow my gut, and if an edit moves me, excites me, or even intrigues me, I know I’ve gotten to a good place. When I was in college, I took a photo-book making class with Jörg Colberg, who was adamant about printing out your work and living with them in the physical realm. He recommended us to hang two prints on a wall that you wanted to sequence together, and to look at them every day, observe how your interpretations morph or break down. It was then that I truly realized that a digital space just can’t compete against the commanding presence of tactile objects. When I’m sequencing, I just use a blank dummy book, cheap prints, and a lot of tape. Simple, unobtrusive, and yields a result that you can physically flip through as you would the final product.

AT: Which photo books are you particularly inspired by?

RN: I was first exposed to the photo book when I was in school, and I remember being really struck by Chris Killip’s In Flagrante, John Gossage’s The Pond, Larry Clark’s Tulsa, and Alec Soth’s Niagara and Sleeping by the Mississippi. That was the first time I saw how an image can transform so radically when seen in a well thought out sequence. I began to appreciate subdued images, the ones that can lurk in the quieter corners of an edit, the mortar that holds an edit together. It can be so tempting to have fifty loud images back-to-back; however it’s hard to tell a poem without pauses, where everything is exclaimed with no room for whispers. Appreciating this can be especially hard in our current age of social media, with everyone competing for that extra second of exposure as we all scroll past our feeds with blinding speed. I am guilty of this as well, and it’s definitely not a bad thing that image-makers are consistently creating these bold, eye-grabbing pictures. But I find it important to take the time to pause and reflect. Getting off the fast lane is so crucial, more than ever really, as life keeps accelerating beyond our abilities to fully grasp our surroundings.

That being said, it has been so reinvigorating to see how the medium has been adapting and evolving. I’ve been recently looking at Thilde Jensen’s The Canaries, Doug Dubois’ My Last Day at Seventeen, Sam Contis’ Deep Springs, and Gregory Halpern’s ZZYZX. I also recently got to see Mathieu Asselin’s Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation and Nick Sethi’s Khichdi (Kitchari), which both really stood out to me as refreshing takes on what a photo book can be.

AT: I can see how many of those photographers influenced you by looking at your work. There is an elegance to your edits that’s really refreshing. Let’s talk about A Distant Land. What was the impetus for the series?

RN: Thank you! A Distant Land was my first serious foray into photography as an artistic medium. While I was in school, I had been struggling with making personal work while living in the U.S., a country that was completely foreign to me at that time. I wasn’t connecting with the pictures I was making, and each time I’d make an edit, it felt as if I was just pushing around images with no weight. Around this time, my professors suggested to search for images when I went home, and as obvious as it is now, I realized I desperately needed to photograph this place I came from.

That following summer I went back to Paraguay, excited to finally have some semblance of direction for my work. I spent the next three years going back and forth, making pictures every summer, then going back to school in Rhode Island to edit the work, indulging in the process every step of the way. I learned so much about myself through this project, both as a photographer and an individual, and I had the beautiful realization that making work was so much more than the end product. Your audience gets to see the pictures, but only you get to carry all the lessons you’ve learned, the people you’ve met, and the experiences surrounding each frame. My good friend recently reminded me to “just trust the process,” a simple statement that continues to carry me through every project, especially when I get stuck and begin to doubt myself too much.

AT: I think “just trust the process” is a lot like saying “endure,” a necessity practically every artist talks about. Because art making is such a mystery—or at least ideally it is—this advice helps make the inevitable bumps in the road a bit more palatable. They’re what create the artwork as much as the breakthroughs. Are there techniques you’ve learned to jar yourself out of times of procrastination, or confusion, or insecurity?

RN: So very true. I’ve lost count of how many times I have gone through these downward spirals of anxiety and insecurity, feeling like I’m losing grip of what it is that I’m doing. Photography has this unique aspect to it, that there really isn’t much of a difference between a “completed” image and a “sketch,” as opposed to other mediums where one can more clearly delineate between both. At the end of the day, it’s how the image or body of work is adapted and disseminated for consumption that adds meaning. I think this is why I keep finding myself confused, wondering if I’m making good or bad work, and what it all means to me as an individual.

What’s funny about all of this is that almost every crisis I experience stems from overthinking things, which I’ve always gotten through by just making more pictures. Going back to the simple act of taking a photograph always gets me out of these ruts, and reminding myself that pictures can be ephemeral, at times even disposable, and that really, no one is going to lambast you for taking a bad picture. When I do get to one of these breakthroughs, it’s this beautiful catharsis that keeps giving back.

AT: I recently read a chapter Ernst Haas wrote in The Joy of Photography, a bestselling book published by Eastman Kodak Company in 1979, and in it he said that “photographing well…is only a step to seeing and enjoying more without a camera,” which I loved. Do you find that photographing has had this effect on you?

RN: Without a doubt. What is photography but the act of seeking that which has been unseen, or at times even intangible? Once you do it enough, this act of close observation begins to seep into your life, opening up the world beyond what you could ever expect. When I started working on A Distant Land, it was as if I was seeing my childhood home for the first time, as cheesy as that sounds. I was no longer just going through the motions of everyday life. I found myself pausing more often, driving down roads I had never been on, speaking with strangers I might not have ever approached otherwise. I became more inquisitive of life itself, not being afraid of asking questions that might seem mundane on the surface and even uncomfortable for some, myself included. But I truly appreciate these moments, because it so often reveals something new about myself or the places I inhabit. Photography has done so much for me. It has given me incredible opportunities and led me to experience the less trodden parts of life. It can be draining at times, but only because I care so much about the medium and its intricacies. I’m pretty sure taking pictures has formed a large part of who I am, and I wouldn’t want it any other way.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.