Sam Gregg on Paul D’Amato

Sam Gregg (b. 1990) is a London born and based portrait and documentary photographer. With a particular interest in marginalised and dispossessed communities, Gregg’s work is both immersive and removed, taking refuge within complex environments as a means of following narratives that reflect on his own culture. He has been published and exhibited internationally, including at the National Portrait Gallery, Leica gallery Milan and most recently Photo Vogue Festival. Commercial and editorial clients include Apple, Lavazza, L’Uomo Vogue and M Magazine, to name a few.

Paul D’Amato was born in Boston, educated in Portland and New Haven and currently lives and teaches in Chicago where he has been photographing for decades. The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation awarded him a Fellowship in 1994 and a Subvention Grant in 2004 and the Illinois Arts Council recognized his work with Grants in 1989 and 2005. His monograph Barrio, Photographs from Chicago’s Pilsen and Little Village was published by University of Chicago Press in 2006.

1: Paul D'Amato, 2: Sam Gregg, throughout the article.

As much as I would have liked one, for whatever reason I’ve never had a photographic mentor. I never studied photography and picked up a camera only after I finished university. I can be quite reclusive and independent, so perhaps that has something to do with it. Although in the age of the Internet, from Flickr to Tumblr and Instagram, a mentor can only be a click and a question away. With that being said though, my mentor is without a doubt my father, who, as a director, was and is still educating me on the finer details of how to use a camera. Although as a filmmaker his advice can only go so far. When it comes to photography, I can credit a few individuals for sparking and maintaining my love for the medium. However, one stands tall above the rest and that’s Paul D’Amato. His images have stayed with me from the first time that I saw them, and to this day they are a constant influence on the manner in which I approach and photograph my subjects.

Perhaps this will be a little different to previous mentor series on Rocket Science Magazine, as I have never met Paul and the extent of our relationship is that we follow each other on Instagram. But that for me is enough; he doesn’t have to say anything to me as his images have already said so much. I’m no academic, so forgive me if this isn’t the most professional piece written. Instead, it comes from heart and feeling.

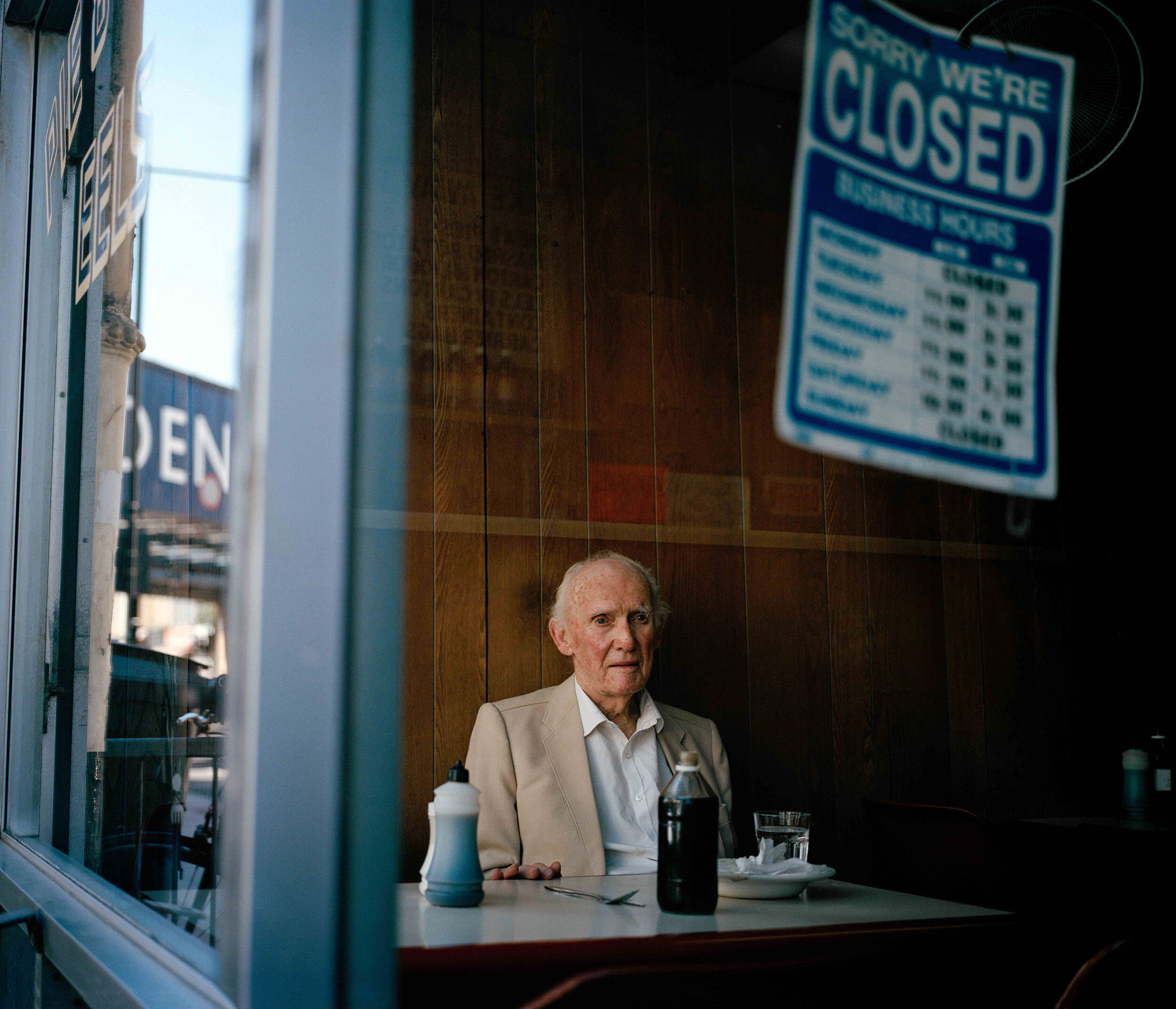

I must have discovered Paul about 4 years ago, through his series Italian Journeys. Perhaps not his most well-known work in comparison to, let’s say Barrio or HereStillNow, but it struck a chord with me as at the time I was dabbling with the idea of moving to Naples to teach English and shoot a project there. Paul’s images definitely acted as a catalyst for me to pack my bags.

My knowledge of Paul comes purely from his visual language. I will ashamedly admit that I have not read all of his interviews until now (either that or I’ve had too many pints and forgotten), which is perhaps a little shocking, but what’s even more startling are the similarities between the way we approach our subjects. From an aesthetic point of view, I can see some strong similarities in Paul’s work and my own and through reading his approach it is not surprising that we have created similar results considering the manner in which we both integrate ourselves into fringed communities.

When Paul speaks, there is an overwhelming sense of the respect that he has for the people that he photographs – ‘I have tried to honor these interactions with pictures that show that each of my subjects is as important as any that have appeared in art.’. This respect is mirrored in the eyes and poses of his subjects, something that you do not get in the works of a Bruce Gilden or a Martin Parr. It is clear that Paul understands the precariousness of the situations that he is in, recognising that he is a white male entering the domains of marginilised, multicultural communities. This is something that I try to adhere to when I am photographing – to tread lightly enough to gain the trust of one’s subjects but firmly enough in order to gain their respect.

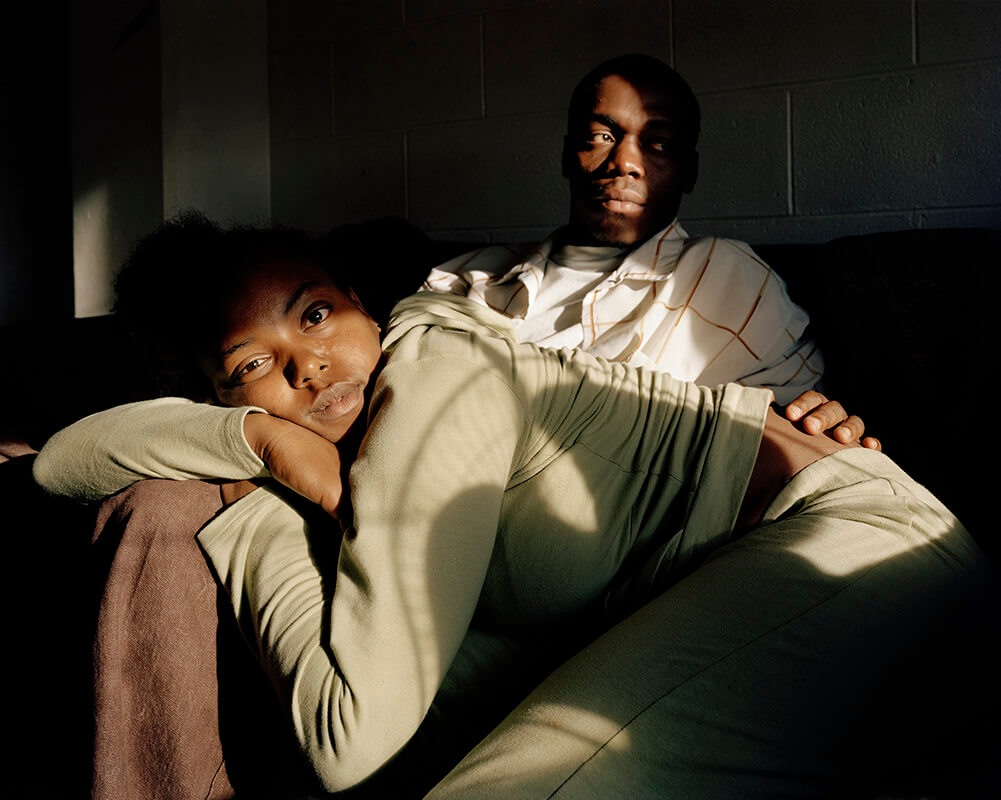

There is a level of intimacy in Paul’s images that I strive to capture in every portrait that I take but by looking at Paul’s work, it is often something I can only dream of achieving. Paul’s portrait in HereStillNow of a young black couple on a sofa lit by streaked window light is testament to his ability to ingratiate himself into a foreign community (Paul being a white man from Oregon – a contrast to the Afro-American community of Chicago that he has entered). As a documentary photographer I know how long it can sometimes take before a subject becomes relaxed. This image, however, is a picture perfect representation of Paul’s calming influence as a photographer. The young woman is slumped across her boyfriend, both with eyes almost drooped to the point of falling asleep, which our primeval past has taught us is when we’re at our most vulnerable. There are clearly highly skilled levels of social psychology and humility at play here. Oh – and amongst all that the ability to perfectly frame, light and execute a shot.

For me the very rhetoric of ‘taking a photo’ is something that I am constantly battling with. ‘To take’ implies a one-sided relationship, with one party gaining something and the other noting. To compensate for this, I have taken inspiration from Paul and always try to bring a print back to my subjects. It doesn’t come from guilt, but more so from the desire to make the project a collaborative one. Not only is it a token of appreciation but it also acts as a kind of return ticket, allowing for re-entry into the environment and the possibility of more photographs, because, as documentary photographers, Paul recognises that we don’t always get the best photo on the first try.

I personally try to give my subjects as little direction as possible, allowing them semi-autonomy over their portrayal and a replication that is as true as possible to themselves and their environments. As Paul in a nutshell states: ‘the subjects perform enactments of themselves, which I shape into a photograph.

There is the age-old quote by Bruce Gilden that goes ‘the older I get, the closer I get.’ This may be true for some but for others, Paul included, it may very well be the opposite. His latter switch to a large view camera, which in Paul’s own words has changed his work from being ‘candid and intuitive to being a lot more collaborative, thoughtful, and deliberate’, is something that I have taken into my own work in the last few years, making the switch from a 35mm rangefinder to a bulky 6×7 Mamiya. I haven’t lost the courage to make candid shots, I have merely become more sensitive to peoples’ emotions and started to take more pleasure in the collaborative act. Paul neatly remarks that ‘what occurs then is a kind of collaboration and performance on both sides of the camera. For it to work, we both have to come to an accord on what will lead to the most emotionally resonant and believable picture.’ I keep these words in mind every time that I’m out in the field.

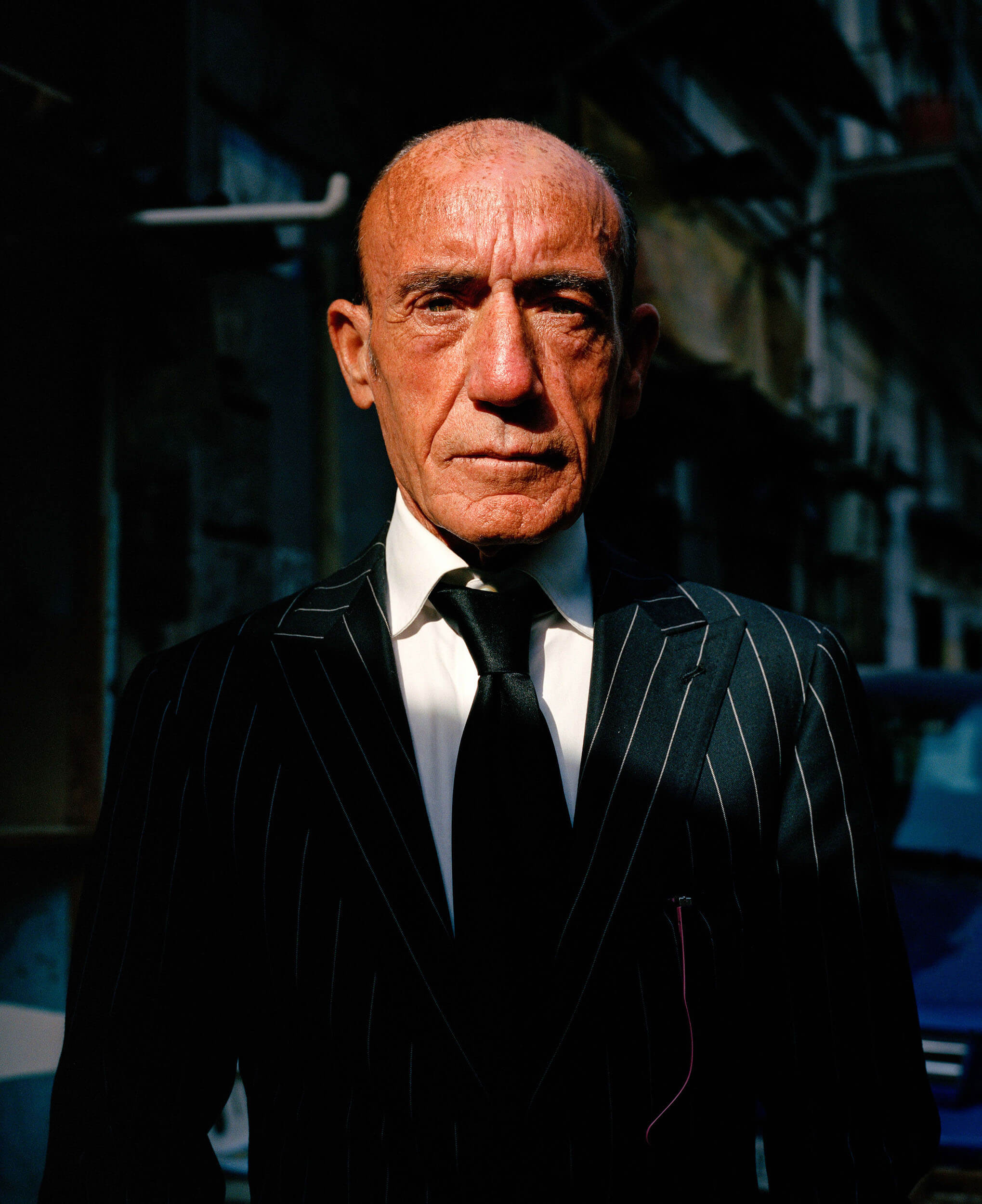

There is also a strong cinematic element to Paul’s work that I try to transpose into my own. Barrio, which contains a lot more candid moments in comparison to Paul’s later projects, naturally contains a lot of cinematic moments. The man peering through blinds beside his exasperated daughter is one that immediately springs to mind. Cinematic moments can be achieved in a variety of different ways, from lighting, to framing, to posing but for me the eyes are his most powerful tools. Even in his recent more portrait-orientated work, there are a lot of cinematic moments. There is a particularly striking photo from Midway of a black man stepping out of what appears to be a car dealership office. It is as if it is a moment frozen in time or a still captured from a movie set. Even the lighting, although clearly sunlight, has an aura to it that is not too dissimilar to the huge tungsten lights found on film sets. The man’s gaze is fixed firmly to the floor and it is clear that he is enraptured in his own thoughts. What is he thinking about? What has happened? Paul’s images constantly keep you guessing and wanting to know more, and this for me is the hallmark of a great photo. Paul’s images aren’t always self-explanatory and he doesn’t give you too much information, just the right amount to keep you guessing. Paul’s work reminds me of a Richard Kalvar quote from a recent documentary in which he describes his work process as ‘creating fiction from reality’.

As mentioned previously, Paul’s ability to capture a human’s soul is something that I strive for in every portrait that I take. There are few photographers who are able to capture such a range of human emotions in their portraiture, from anger to sadness, to fear and anxiety. For me, it is the hardest skill as a photographer and is testament to Paul’s abilities. It may sound cliché but I truly believe that the eyes are the windows to the soul. In that case, Paul must moonlight as a window cleaner with a hall pass to the soul.

Above all however, the greatest testament to Paul’s work I can give is that his images stay with you. They are engrained in my mind, and in today’s social media driven society in which we are bombarded by thousands of images everyday, that is no mean feat. His work easily slices through the mass of imagery that has accumulated in my mind. If you were to say the name of any well-known photographer to me, I could visualise 2 or 3 of their images within a few seconds, but with Paul’s work I can easily envision 5 to 10 in a heartbeat. Now, perhaps that doesn’t seem like that many, but any photographer reading this will understand what I am talking about.

Paul will forever be a mentor of mine, not only for the aesthetic beauty of his images but also for the courageous and dignified manner in which he tackles delicate socio-political and economic difficulties faced by some of societies most vulnerable and marginalised communities.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.