Studio visit with Shane Lavalette

Shane Lavalette is a photographer, the founding publisher/editor for Lavalette and the director of Light Work, a non-profit in Syracuse, New York. In 2016, Lavalette published his first monograph, One Sun, One Shadow, and a solo exhibition of the same title was held at Robert Morat Galerie in Hamburg, Germany. Lavalette’s projects have been featured by the New York Times, TIME, NPR, CNN, the Telegraph, Foam Magazine, and Hotshoe, among others; and his editorial work has accompanied stories in various publications, including the New York Times Magazine, the New Yorker, Bloomberg Businessweek, The Wire, Wallpaper*, Monocle, and the Guardian.

Allison Beondé is a visual artist living in Central New York. She holds her BFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in partnership with Tufts University. She has exhibited work throughout the Northeast and is the recipient of a 2015 Traveling Fellowship through the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, a 2015 Light Work Grant, and a 2016 Artist Grant through The Canary Lab at Syracuse University.

Pauline Magnenat: Where is your studio exactly and how long have you been working there?

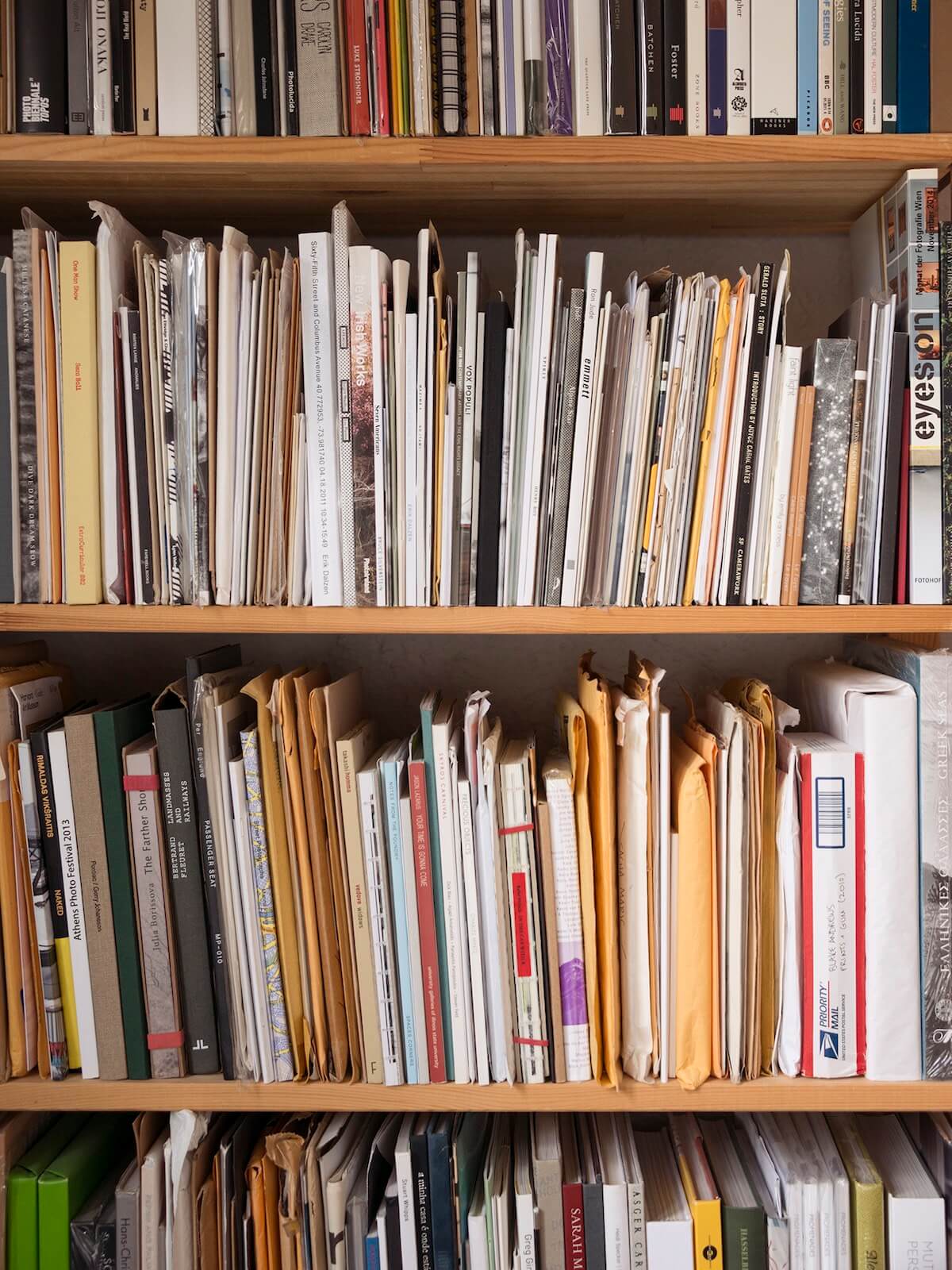

Shane Lavalette: While I was living and working in bigger cities like Boston and New York I didn’t have the financial ability to afford any extra space and always shared apartments with roommates, so my “studio” was generally just my laptop in my bedroom. It was primarily a virtual space. I stuffed boxes of prints and framed works in the closet, put some work on the walls, etc. Unlike other mediums, I think photography is a little more forgiving in this way. Since moving to Syracuse a few years ago, though, I’ve had the luxury of a bit more living space. In October of last year, I moved into a three bedroom house, where one of the bedrooms is now a dedicated office/studio. It’s still being unpacked and organized, but it’s really a treat to have a space that’s purely intended for making work.

PM: What are the pros and cons of your studio?

SL: Well, it’s certainly convenient and comfortable, gets decent natural light, and is very walkable to the kitchen to get food or coffee (big bonus). There aren’t many cons… I suppose it’s not really a space where I’d want to make a big mess, because I’d also have to live with it. I tend to prefer a fairly minimalist living space for thinking. I still romanticize the idea of a big lofty artist studio where I can experiment with other media a bit more freely. Maybe some day.

PM: Can you talk a little bit about how you came to work at Light Work and what a typical day there includes?

SL: Sure. I actually ended up first coming to Syracuse as an artist-in-residence at Light Work, in August of 2011. I shared the apartment with Lithuanian photographer Andrew Miksys, who has since become a good friend. The month-long residency was a really fun and productive experience for the both of us, and it was my first time spending time at a place like Light Work—an artist-run space that has great equipment, knowledgeable staff, and a really wonderful community connected to it. At the time that I did my residency, there was a position that had just opened, and so I applied for it on a whim (thanks in part to the encouragement of Doug DuBois, who teaches nearby at Syracuse University). I was trying really hard to sink my teeth into the arts community in Boston at that time, and searching for a few years for an interesting job in the arts—to no avail. So when I found out they wanted to offer the position at Light Work to me, I jumped at the opportunity. It has proved to be a challenging job, but each day is different, and I continue to engage with the kinds of things I was looking to do before I was hired—curating, publishing, etc. I’ve also learned a lot about running an organization, hosting a successful residency experience, grant writing and fundraising, marketing, and many of the other administrative things you’d expect to be a part of the day-to-day at a non-profit. The most rewarding aspect of the job is simply being able to work with so many other artists and help to support the evolution of their projects, ideas and careers.

PM: How do you manage to keep a balance between your work at Light Work and making your own photographic work?

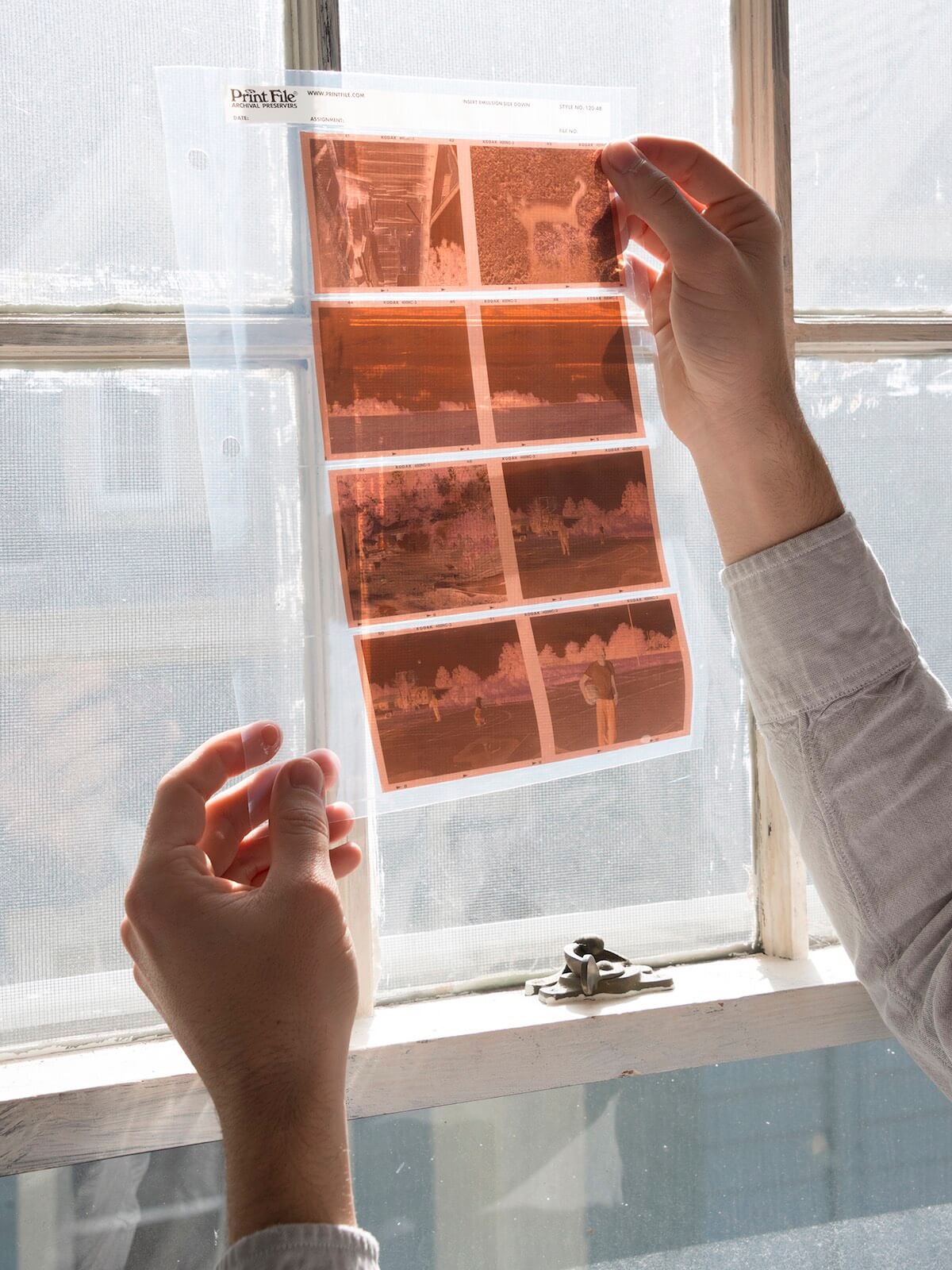

SL: That continues to be a challenge with only so many hours in a day, but I like knowing that I have so much at my fingertips. Naturally, since being here, I’ve scanned and printed all of my projects at Light Work. The lab team are an amazing technical resource, and do really great work for a fraction of the cost of the printing bureaus in bigger cities. Many artists don’t realize that the lab offers these services to artists around the world—not just the artists-in-residence or local lab members. Not long ago I made a set of prints through the lab, for a solo exhibition at Robert Morat Galerie in Hamburg. This coming year, I’ll be printing for a few more shows as well, including for one in my hometown of Burlington, Vermont. I feel very fortunate to have access to the space in that way, it’s just a matter of making the time for it.

PM: What excites you most about photography?

SL: I’m still excited about looking at the world, and the way photography offers the ability to see something in a new way. Taking pictures gets me to pay attention to something that I might not have noticed, and has certainly brought me to places and situations that I wouldn’t have a reason to be in otherwise. I love that. The world is so saturated with images, but a day doesn’t go by where I don’t encounter the feeling of awe or surprise at something visual.

PM: Do you think one can learn a way of seeing?

SL: Seeing is a lot like reading, and making photographs a lot like writing. As with words, I think everyone can find their way with images, as well as forge new trails, develop new visual languages, etc.

PM: What’s the best thing you’ve seen recently?

SL: As news and social media feeds are just brimming with awful stories, there’s barely room for everything else. I recently heard a story about an elderly couple that both died simultaneously while holding hands together in bed. Who knows if it’s true or sensationalized, and it’s another sad moment I suppose, but also sweet… A nice little reminder that the world can be pretty amazing.

PM: How much do you shoot on a weekly basis?

SL: I take a fair amount of pictures with my phone, usually daily, but I don’t tend to bring a bigger camera with me often. I think I take better pictures after extended periods of looking. My phone (and my Instagram feed, an extension of it) is just a place for sketching right now. I do some occasional editorial/commercial work, when the assignment is interesting. It’s always a challenge and tends to push me outside of my comfort zone, which I think is a healthy exercise as an artist. I also just spent some time this past summer working on a new photography project, which I’m excited to edit and share in some form in the new year.

PM: Does editing your work come naturally to you?

SL: I’d say that I’m a better editor of other people’s photographs. When I look at someone’s work it’s easy for me to decide which images are strongest and most necessary for a project. I feel it’s harder to edit your own work, maybe because you have associations with the places, subjects or experiences of making the image. The things you see in an image you made don’t always translate to the viewer. That said, I do enjoy the process of editing and make significantly more time for that than I do for shooting. It’s important to have people close to you or other artists you respect to share work with during the editing phase. Art is subjective, so you have to take everyone’s feedback with a grain of salt as well, but having people that you trust to bounce things off of is really helpful.

PM: What do you look for in a strong image?

SL: Sometimes the most simple images are the most affecting. I like an image that asks more questions than it answers. Sort of like the feeling of seeing something out in the world that you are drawn to, a good image will tug at you and perhaps even find a lasting place in your memory.

PM: What makes something worthy of being photographed for you?

SL: Almost anything or anyone can be an interesting subject to explore, so it’s up to the artist to find a way to translate what they see into something meaningful. The practice of careful looking that I mentioned is really significant—it helps me remain open and to see things I might not otherwise gravitate to.

PM: Do you think people understand photography?

SL: There are many layers to an image or piece of art and I think we can peel those back to understand different aspects of human experience, emotions, ideas, etc. It’s interesting how much more visually literate we are becoming as a culture. It seems that we are growing exponentially more attuned to images. This really expands the audience for artists using photography. Still, there’s always something more to see in an image, even for those that study photography seriously. Time’s role in how pictures are understood is also completely fascinating to me.

PM: What is your favorite track to edit photos to?

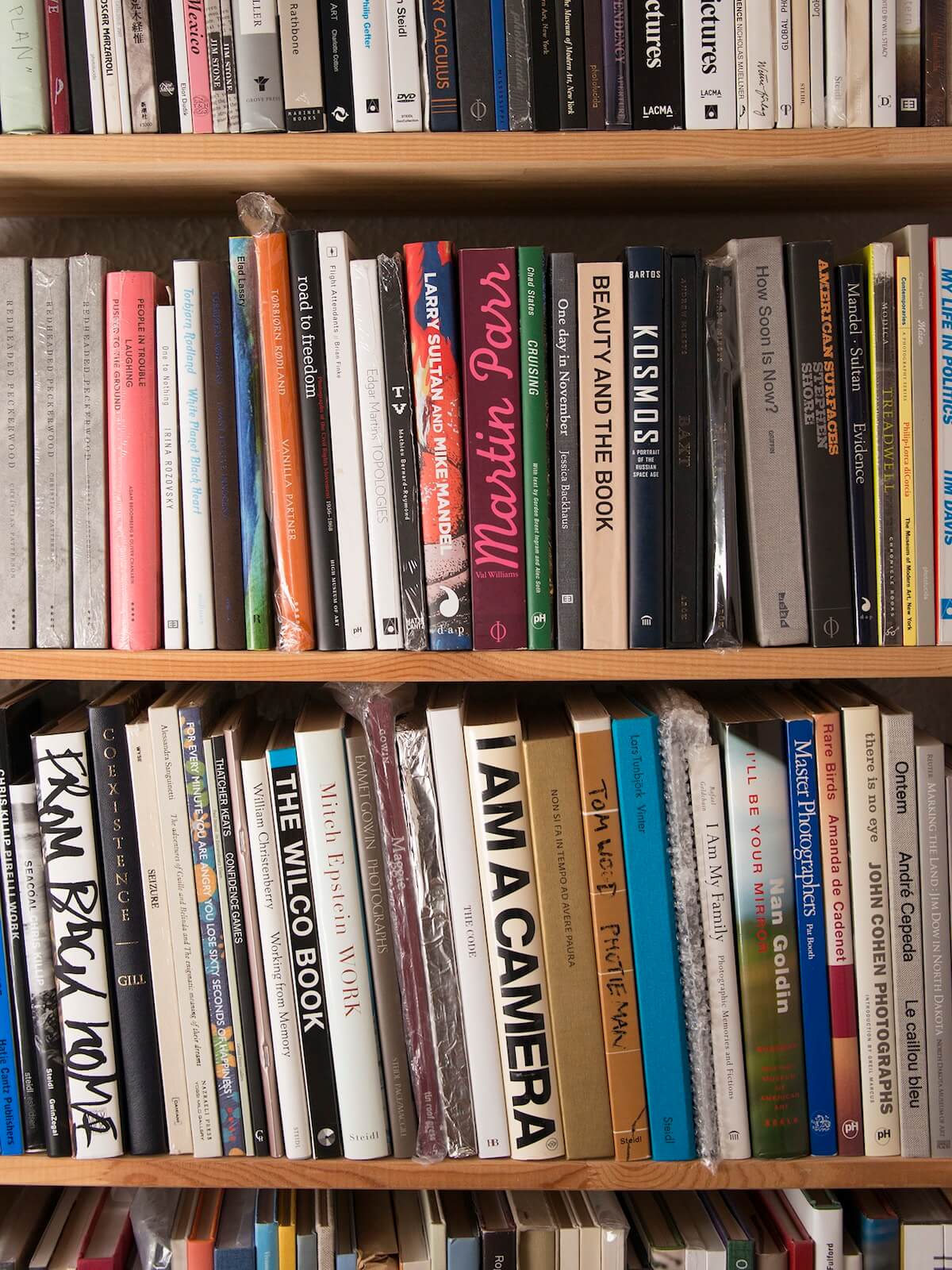

SL: I’m not really a record collector per se, but I keep some LPs and a turntable in the studio because there’s nothing like some good music while working. I’ll play everything from indie rock to jazz, electronic to classical. Lately, in those genres, it has been Quilt, Thelonious Monk, James Blake, and Brahms.

PM: Your latest work, One Sun, One Shadow, is now being released as a book. How did you get commissioned by the High Museum of Art to make a project about the South, and why did you choose music as your point of entry?

SL: The High Museum of Art’s “Picturing the South” series is an incredible initiative that they have been doing for a number of years now. Past artists that have been commissioned include Sally Mann, Emmet Gowin, Richard Misrach, and Alec Soth, amongst others. I was completely honored to be invited to be a part of the project, especially as a young artist who admired many of the others that had participated in it already. It was a bit intimidating of course, but an incredibly exciting opportunity for me to pursue a project in a way that I wouldn’t have otherwise been able to. Being from Vermont, and having only lived in the Northeast, I didn’t have a personal relationship with the South, but rather an idea of it that was influenced by things like films, the history of photography, and music. I think Julian Cox, who was at the High at the time, was interested in this perspective as a compliment to some of the artists they had worked with who were native Southerners. I chose music as an entry-point for a few reasons. At the time I was getting really interested in old time, blues, and gospel songs, and the stories they told about life, labor, religion, race, love, death, etc. I was really starting to see music as an oral history. I thought it would be interesting to embark on a project that explored the themes of traditional songs through the contemporary landscape of the South. I was also interested in the notion that our understanding of a place can be informed by sound, and that music is very much a reflection of the place where it is made.

PM: What was your itinerary like?

SL: I was commissioned in 2010 and spent that entire summer living out of my car, camping and staying with friends and strangers. I drove down to Florida from Boston, and then wandered through parts of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, the Carolinas, etc. I set out with a general idea of some places I wanted to spend time, given their musical significance (Clarksdale, MS, Memphis, TN, or Athens, GA, for example) and some people I wanted to meet, but wanted to leave things open to the unexpected. I was primarily interested in the landscape and history of the “Deep South.” The following year I also traveled for a portion of the summer, with an interest in seeing some of the areas I hadn’t traveled through yet. Beyond that, I think I made one or two shorter trips for specific things. I worked on the project for about two years, and a portion of the work was shown at the High Museum in Atlanta in 2012. Naturally, I fell in love with the South during my travels. There were many places I didn’t get to spend time and that did not make their way into the pictures, but I wasn’t interested in systematically documenting the region. I was simply looking for things that resonated with me at the time.

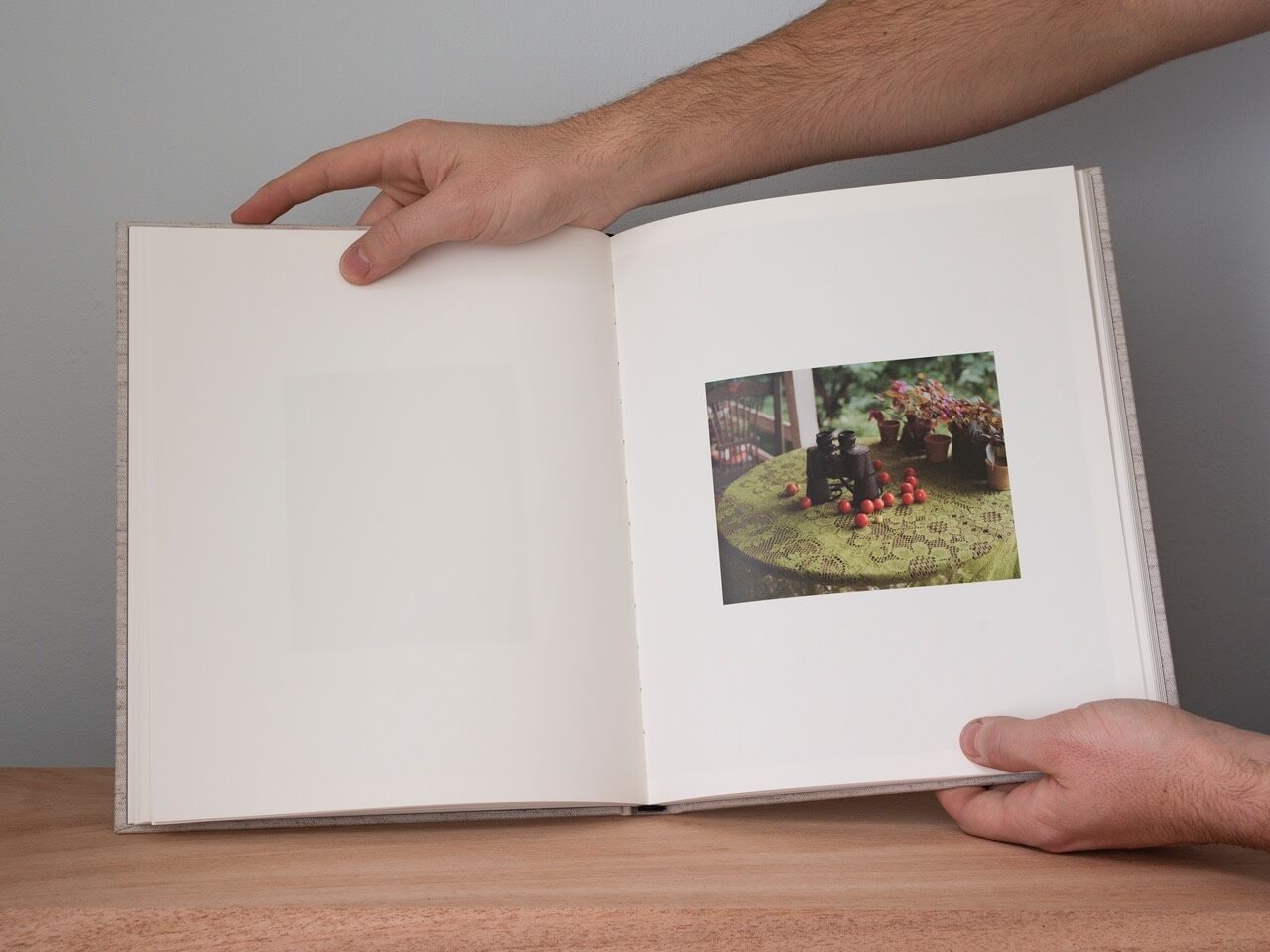

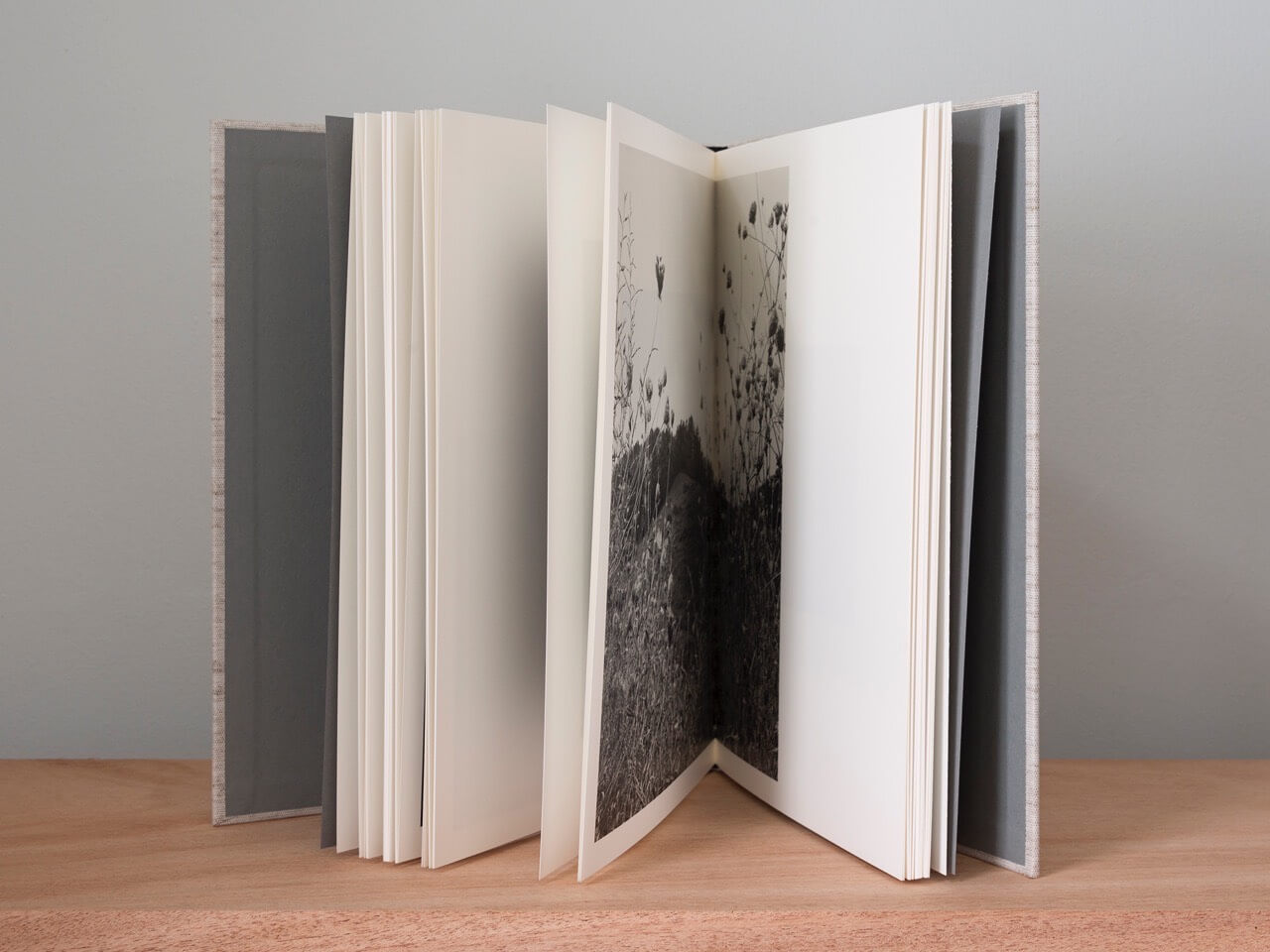

PM: In his essay included in the book, Tim Davis writes that you “smartly decided not to make a documentary about musicians, but instead scoured the landscape looking for the feeling coming from the music.” Can you talk about why you made this decision and what feeling you ended up encountering?

SL: I knew immediately that I didn’t want to set out to illustrate significant places and people that are a part of the musical history of the South, or directly trace any specific lineage. I wanted to explore the subjects on the fringes of these places, and focus on the atmosphere. In the essay, Tim also writes about how the photographs come together, and build to something. I think this is especially true in the book, where the movement of the pages leads the viewer, and the memory of an earlier photograph can alter the experience of a later one. That’s one of the things I really love about photo books.

PM: What’s next?

SL: I’m really happy to finally have One Sun, One Shadow out in the world. After working on this project for a few years, I’m eager to share it with those who might appreciate it. In terms of new projects, I have a few things that I’m developing simultaneously. One of them is a commission in Switzerland that is supported through a collaboration between Fotostiftung Schweiz (the Swiss Foundation for Photography) in Winterthur, Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne, and Swiss Tourism. It’s still a little early to talk about, but the project I am doing combines a new series of images that I made with reportage work by a Swiss photographer, made nearly eighty years earlier. Again, I’m thinking a lot about history, place, and time. More info about this project will be announced soon, and an exhibition and publication will launch in February 2017.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.