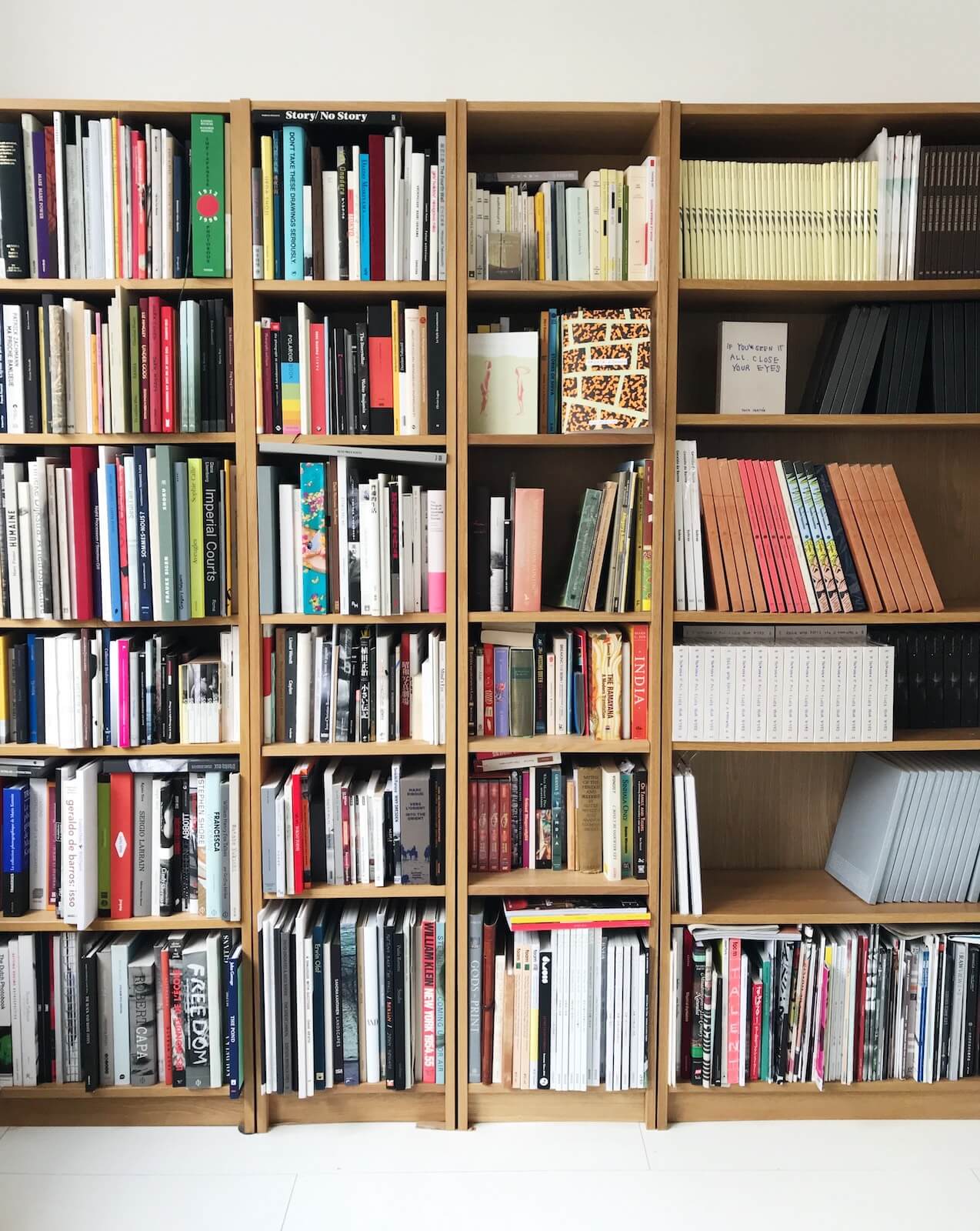

Studio visit with Chose Commune

Chose Commune is a French independent publishing house in the fields of photography and works on paper. Chose Commune makes book-objects with bold editorial and design choices. Chose Commune presents emerging artists as well as well-known figures with unpublished material. Chose Commune was founded in 2014 by Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi and Vasantha Yogananthan.

Kelsey Sucena is a photographer, writer, and park ranger. Their work rests at the intersection of photography and text, often within the bodies of performative slideshows and photo-text-books. Kelsey is an MFA candidate at Image Text Ithaca (2020).

Photographs of the books spreads and bookends by Andreas B. Krueger & HoTeng Chang

Photographs of the Chose Commune studio and portraits by Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi & Vasantha Yogananthan

Photographs of the books spreads and bookends by Andreas B. Krueger & HoTeng Chang

Photographs of the Chose Commune studio and portraits by Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi & Vasantha Yogananthan

Kelsey Sucena: Cécile and Vasantha, it’s a real treat to have you join us for this issue of Rocket Science. First I just wanted to thank you for taking the time to talk about your shared publishing project, Chose Commune (CC). I’m curious to learn a little more about your individual backgrounds and about what brought you together on such an ambitious venture. Can you tell us about how you met and what it was like when you first decided to work together?

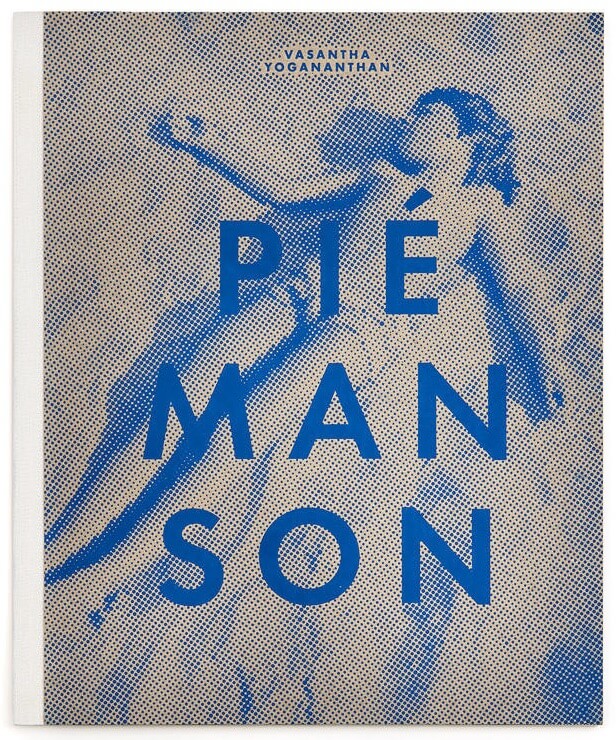

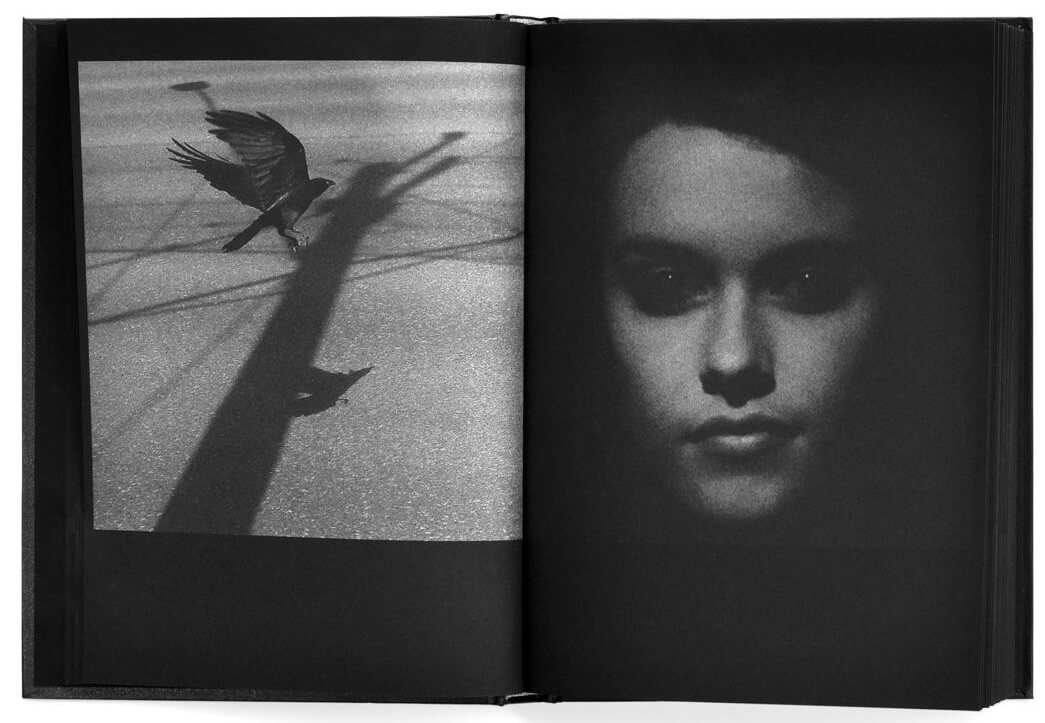

Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi: We are a couple so that’s how we met. It’s not a rare thing to create a business together as a couple but what was more unusual about us it that we started CC almost at the same time as our personal relationship, meaning we’ve been growing as partners in work and life simultaneously. We first started working together with Vasantha’s first book, which was also CC’s first book, Piémanson, published in 2014. Vasantha had been looking for a publisher but most of them were asking to finance the book, which is something he couldn’t and wouldn’t do. That’s when we thought, why not publish it ourselves… And since we both love books, we knew from the start that we wanted to publish other artists as well. It was never about only self-publishing Vasantha’s work.

KS: That makes sense. I’ve heard from quite a few artists who have had similar issues with publishing and finance. Many are drawn to self publish but with CC you’ve taken that a step further by inviting other artists into the fold. I’m familiar with Vasantha’s work, but I’d love to know more about you Cécile. Could you tell us a bit about your background, and about how it influences the work you do at CC?

CPK: Before CC and whilst doing CC (I was working part-time at a gallery for the first two years before going full-time), I was working in different fields within the photography industry, in France and overseas (Japan, UK): a company, a gallery, a museum, a photo agency. I never stayed at any of these jobs very long because a lot of them were internships and short-term contracts. It was definitely unstable but it taught me a lot as I experienced many sides of the industry. I had no experience in publishing though, which was a chance, I think. Being self-taught makes you bolder, you’re like a child in a way, learning by doing… Actually, I’ve not only been self-taught on CC but from the start of my career as I haven’t studied art history, photography, curation or design. I did a master thesis in Japanese and Chinese and my interest in photography came by chance with an internship I did at the Photography Museum in Tokyo. It all started from there.

KS: And Vasantha, do you feel your experience as an artist shapes the way you engage with CC’s various projects?

Vasantha Yogananthan: Of course it does. When a photographer presents us a project I can not help but ‘read’ it through my own experience. At the same time in the framework of CC, I quickly switch to publisher. It is not a hard thing to do as I started my career working as a picture editor in a photo agency in Paris. I am self-taught and I have learn pretty much everything by editing other photographer’s pictures. What is perhaps specific with my double status is that sometimes I have an idea of a specific book design I know would not fit my own work and I wait eagerly for the ‘right’ photographer’s work to make it happen.

KS: Your interests obviously intersect quite a bit but your experiences and skills are fairly unique. Where and how do you find yourselves coming together? Do you think that the collaboration makes for stronger work?

CPK: For some projects, we exchange and decide together who we want to publish. For other projects, I approach artists I am interested in and start a conversation with them, without having Vasantha particularly involved. Of course, collaboration makes for stronger work. But not only collaboration between the two of us, but with the team involved on the projects.

VY: There is a funny thing about us concerning editing. Leave the two of us in two separate rooms with the same 500 prints and ask us to select only 50 of them. You will end up with the same selection! Our shared sensitivity to the art of editing and sequencing is what makes our collaboration as publishers truly special.

KS: Do you each have specific roles at CC?

CPK: Although we co-founded CC together, I am the one running the publishing house, from both a creative and administrative point of view. I manage every project from concept to delivery, speaking with the artists, managing the designers, lithographers, printers, translators, proofreaders etc. For some of the projects, Vasantha will be doing the art direction with me, working on the editing and sequencing, and for other projects, he won’t get involved at all, only giving me advice when I need… And sometimes discovering the book as it’s published!

From Piémanson, by Vasantha Yogananthan

KS: Where were you in 2014 as artists and individuals? How did CC change things for you?

CPK: As I said earlier, I was juggling jobs and doing a bit of freelancing. CC changed everything for me, as I came from having an unstable job to owning and managing a business. There was a lot of joy and excitement but also a considerable amount of responsibility, which was very daunting.

VY: I was struggling to make a living as a photographer. I was doing all kinds of boring assignments to fund my personal projects. CC certainly did not change anything money-wise but it did a lot in shaping my understanding of photography. It was a space to experiment and to do my stuff without waiting for anyone to approve my work. I could make work, publish, make work, publish, and I could do it because we had the structure and the distribution network for it.

KS: Was there anything you felt wasn’t being done – or being done well – in the publishing world that CC could do – or do better?

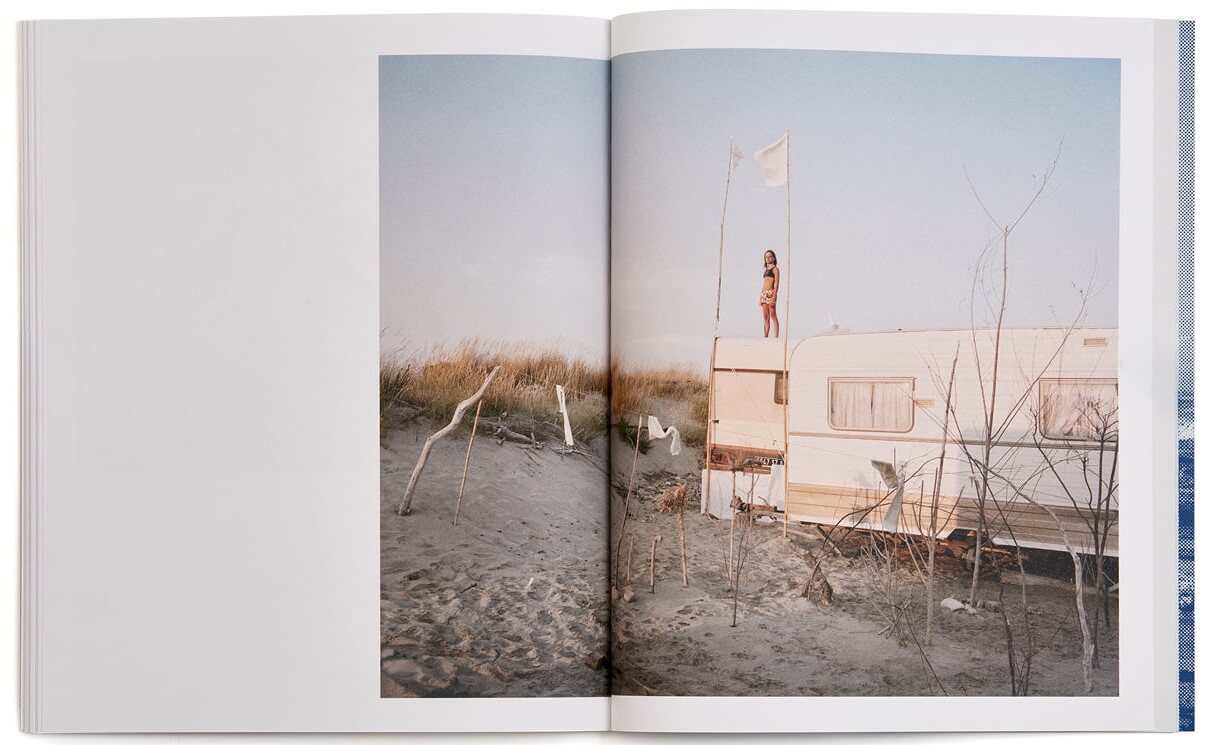

CPK: I don’t think it was about doing things better. It would be slightly pretentious to think that way as young individuals and especially in France where we have a strong tradition of art book publishing, It was more about doing things differently, with our own voice and at our own pace. We started by doing one book a year, and now we’re doing about 7 a year. I think the two things we did differently are that first, we’re working on a distribution network by ourselves, with no help from a distributor (we only have a distributor in Japan, and have just started working with one in the USA). Apart from these two, all of our distribution, whether it is for France, Europe or the rest of the world, is managed in-house. The other thing we do differently is that we are very much interested in unpublished works by well-known and/or overlooked artists. This is what led us to make a book with photographs by Shoji Ueda, Geraldo de Barros and this year, Issei Suda. We love looking into the archive of a great artist we admire and offer our own vision on the work. It’s a great honour too, being granted the access to the work and have the freedom to make something new with it.

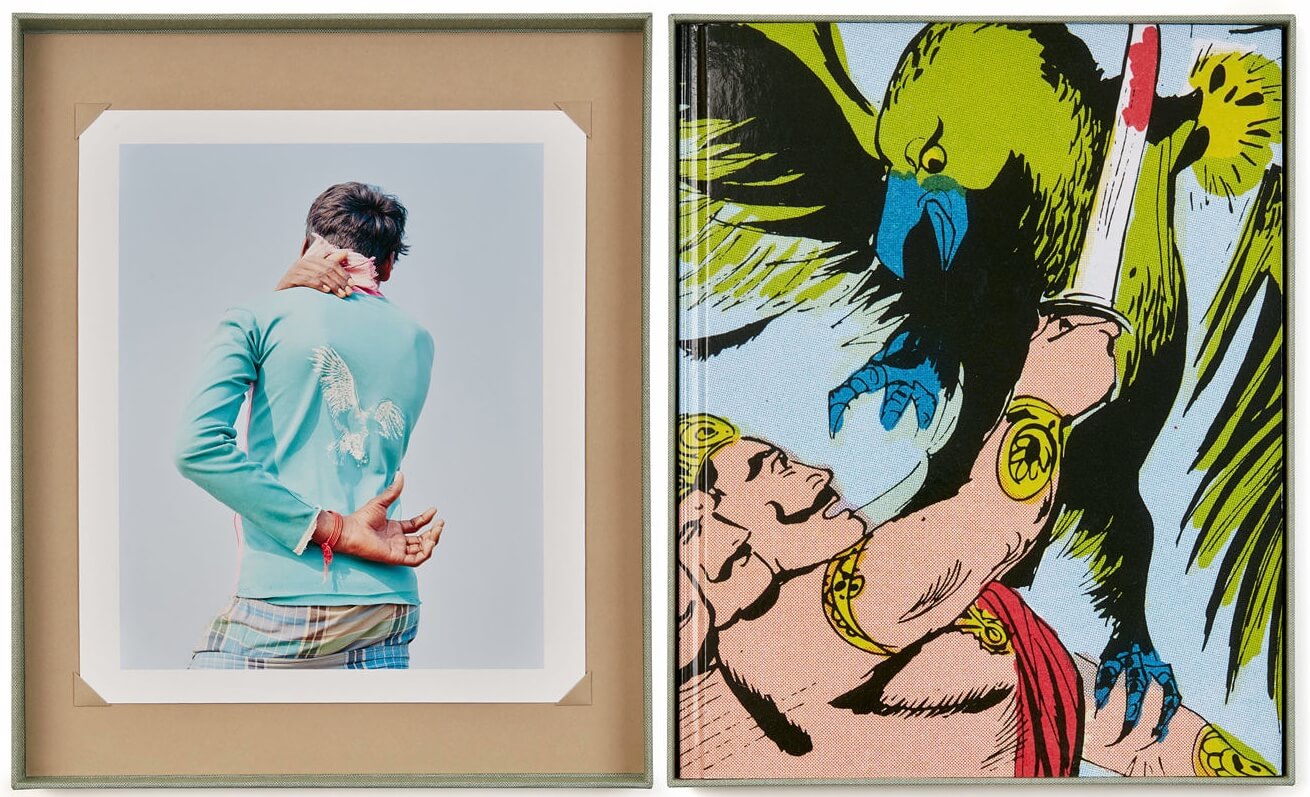

From Shoji Ueda's Special Edition, by Shoji Ueda

KS: Where exactly did the name Chose Commune came from?

CPK: Chose Commune comes from the latin term “res communis”, which means “thing of the entire community”, “the common heritage of all mankind, not subject to the appropriation by or sovereignty”. For example, water, sea, air are all res communis, as they can’t be owned. We liked the idea that books, although they can be bought, are not made to be owned by one person but to move around, from one hand to another.

KS: I love that idea, the book as a common space. I think we’ve been fortunate over these last few years to see such a boom in the photobook world. It must have felt like a monumental task to start an independent publisher at a time when so many others were competing for the spotlight or also just getting off the ground. What were some other factors which led you to found CC?

CPK: It was first and foremost a necessity as Vasantha was looking for a publisher for his first work, but it was also definitely because as a book lover, I wanted to experience making a book myself. It was a bit naive when I think of it! It also had a lot to do with the fact that I had always been quite entrepreneurial. I was already doing a bit of project management and translation as a freelance, and I loved the freedom of it. It was a great opportunity to start doing something I love, in good company.

VY: There is an analogy with the music industry: either you go sign with a major or you start your own label. I am a big fan of hip-hop and the idea to be independent has always been part of this music genre. When you start your own publishing house, you go through so many issues – first of all business wise and admin wise. You better learn fast to stay alive. Most importantly you do things your own way and this is the thing I still cherish most about CC. When I shoot an assignment for a client I hand over the pictures and I have no say on the selection. When I do an exhibition there is always a lot of compromises to make. When I publish a book as long as things stay within budget we are the ones in charge.

KS: Yes! I absolutely resonate with this analogy to the music industry. It’s interesting to think about how platforms have changed over the last few years. In music there has been a huge uptick in the number of folks who are independently sharing their work through soundcloud, bandcamp and other online platforms. I think photography and art have experienced similar shifts with the development of social media and Instagram especially. There was a moment when folks were even questioning the relevance of book making in the 21st century, and yet we know that people crave photography books and other printed media almost in spite of the digital. Why do you think people are still drawn to art books, and to CC especially?

CPK: Art books can only be experienced on paper. You can read an e-book, although the pleasure certainly isn’t the same as holding a paperback novel. But an art book, it’s all about the choice of paper, the printing… How can that translate on a screen? And for CC, I guess it’s our approach to the medium, and to other practices too? I think one can feel that we’re quite open-minded in the sense that we don’t only publish one type of photography. As long as the body of work is good and within our taste, we can probably consider publishing it. Whether it’s more conceptual (Astres Noirs), documentary (I Called Her Lisa Marie) or fine art (Stickybeak). Also, we never had theoretical writings and essays in our books. When there’s text, it’s either a few simple lines on the subject, or a work of fiction. And I think it’s something people are drawn to.

VY: Perhaps the experience of holding something still prove irreplaceable? For example, where does our obsession for family photo albums come from? Probably because they are objects. They were done slightly differently in each family, they have faded through time, they have worn out after countless viewing. The family album is a subject matter that has been tackled by many curators and writers in the art world, perhaps because families in the 21st century don’t do photo albums anymore. We live in an era of compulsive picture-making where 99% of the photographs end up in a vacuum. How many parents browse the digital archive of their children growing up? I think people who still visit bookshops are looking forward to the physical experience, the same way we do when we go see an exhibition, the same way we do when we hold an old family album.

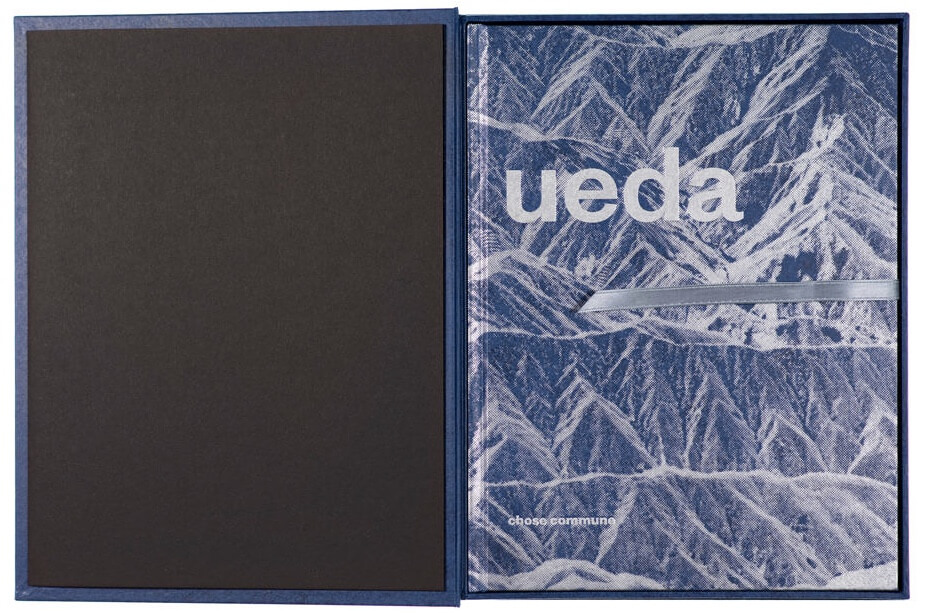

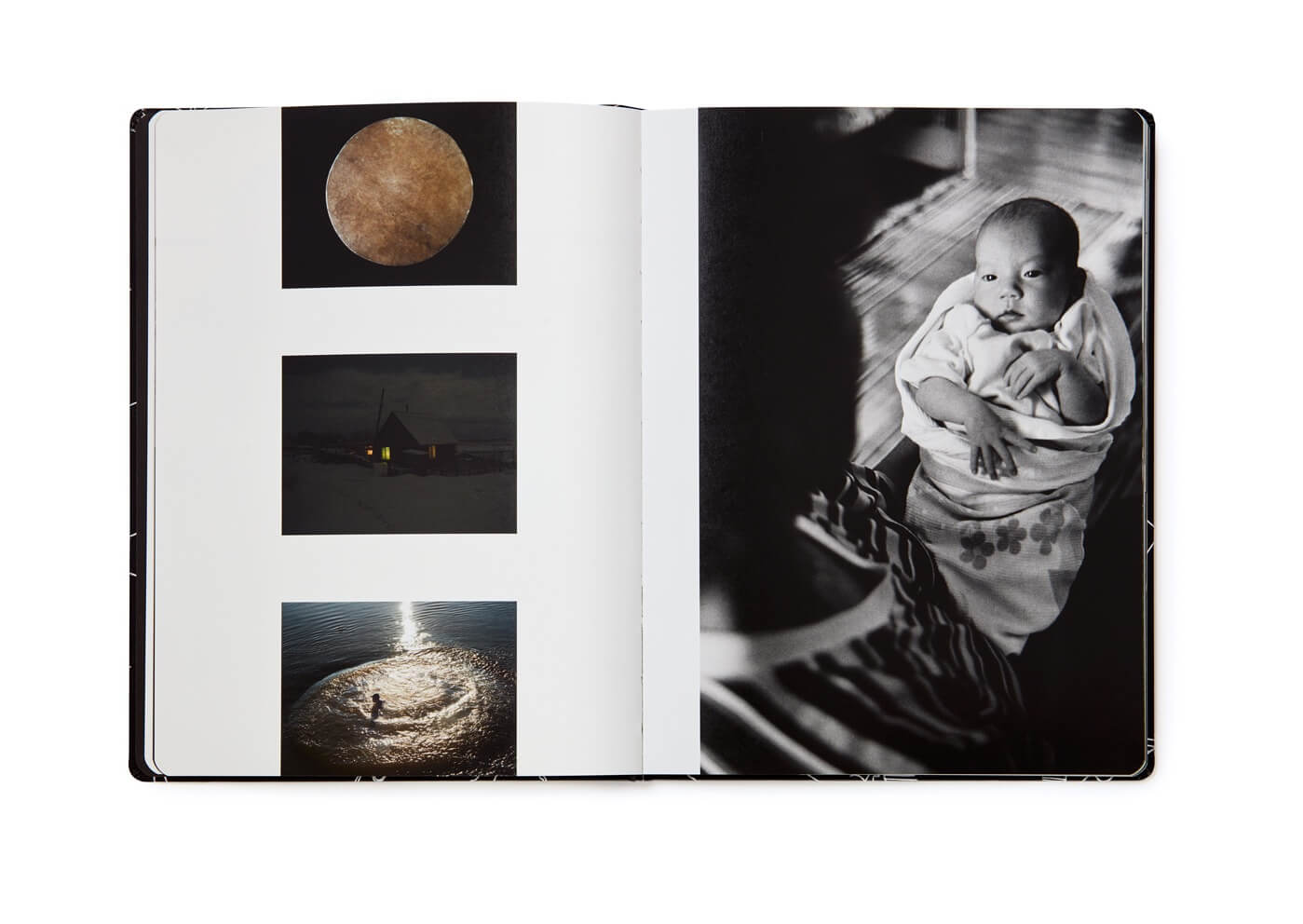

From Astres Noirs by Katrin Koennig and Sarker Protick

KS: As a small publisher making a physical book you’re in a position where you really have to consider that final product. You have a budget to keep in mind, materials to experiment with, and networks of distribution to build. What are some of the unique challenges and limitations you face at CC?

CPK: The biggest challenge is to make the book the way we have first imagined it, but within reason. You always end up making choices, even if we get a grant to help us with the fundings. For example, if we really want to use that very expensive cover material, we’ll use a cheaper interior paper, or the other way around. It’s all about where the attention primarily is. Sometimes the interior paper is much more important than the cover itself to experience a specific body of work, sometimes it’s more about the binding, etc. The networks of distribution were also a hard part. I spent an incredible amount of time building and expanding the network. I used to go door-to-door and visit the bookshops I liked. If I was in a foreign country for a weekend with a friend, I would still have some books in my luggage and take some time to go and see potential resellers. It was compulsive!

KS: Do you feel like that those limitations are helpful? Do they produce more meaningful, or more satisfying work?

CPK: Yes and no. It is helpful to make you learn, as it’s always a good lesson to make something within a budget. But I wouldn’t say no to a fully-funded project on which I could go wild.

KS: I enjoy thinking about the term ‘Book-object’ in relation to what you’re doing at CC. CC is one of my favorite publishers to visit at any art book fair in part because your books are always so solid in the way that they’re designed and built. They’re pleasing to hold and the design always works well with the images inside. I feel like, as a collector who has the fortune of not always considering those things so intimately, it’s easy to lose track of the importance of this side of publishing. What are you thinking about through each stage of the design and production process?

CPK: There’s so much to think about! Before the design and production comes the editing and sequencing, which are always the first steps. Once this is done, we handle a first rough lay-out to the designer, who will be making proposals. We usually have a strong vision on every book, from the lay-out to the cover and materials. But the designer’s eye is essential, he/she makes our ideas come to life. Production isn’t a piece of cake either. That was and still is the hardest part, especially as I’m self-taught. Some publishers hand this part over to the designer but for me, it is important to do it myself as I would never have learnt otherwise. It’s so technical and it requires a lot of attention, patience and preciseness.

VY: There is a ‘luxury’ we have never given up on: taking as much time as we need to publish a book. Sometimes things go pretty fast, sometimes it takes several months or even years. For example the book Behind The Glass by Alexandra Catière got published the way it is because we did not give up. After six months with the edit pinned up on the walls we still could not find the right design until a crazy idea arose… I think the idea of crafting a book as if it is an artist-book – but to find a way to make it work production-wise and budget-wise in a 1000 copies print run – is paramount to CC’s ambition. We believe in the creation of book-objects affordable in a democratic price-range.

KS: I’ve heard a few publishers and art book makers with similar concern for the democratic nature of art books. It reminds me of your explanation for the name Chose Commune, the way that books help create and give access to a shared intellectual commons. Book makers often have an appreciation for the need to make the work accessible and affordable.

VY: As an artist if you are represented by a gallery your work get sold for prices that are not affordable to most people. It is fine as it is a good way to keep funding your personal projects but on the other hand I would like my work to be seen and be available to all through the book medium. This is why at CC, if a first edition runs out and we feel there is a strong demand for a second one we always go ahead.

KS: How do the pure logistics of production cost limit or impact your creative decisions?

VY: If you produce between one and ten copies of an artist book, you can go wild and do whatever you want to do. When you do a thousand copies of an offset printed book, production issues quickly rise up. The idea as mentioned above is that CC is trying to bridge the gap between these two worlds.

KS: And, besides money, what other limitations to books impose on the understanding and reading of artwork?

CPK: There’s no limitation really, as long as we respect the artist’s vision and not transform it into something completely different that he/she wouldn’t want us to do. Especially when working with an estate, it’s essential to be extremely respectful to the way the prints look like. With a contemporary artist, shall he/she agree, you can cut off some elements, make it bleed over the gutter, etc, if it serves the purpose of the book.

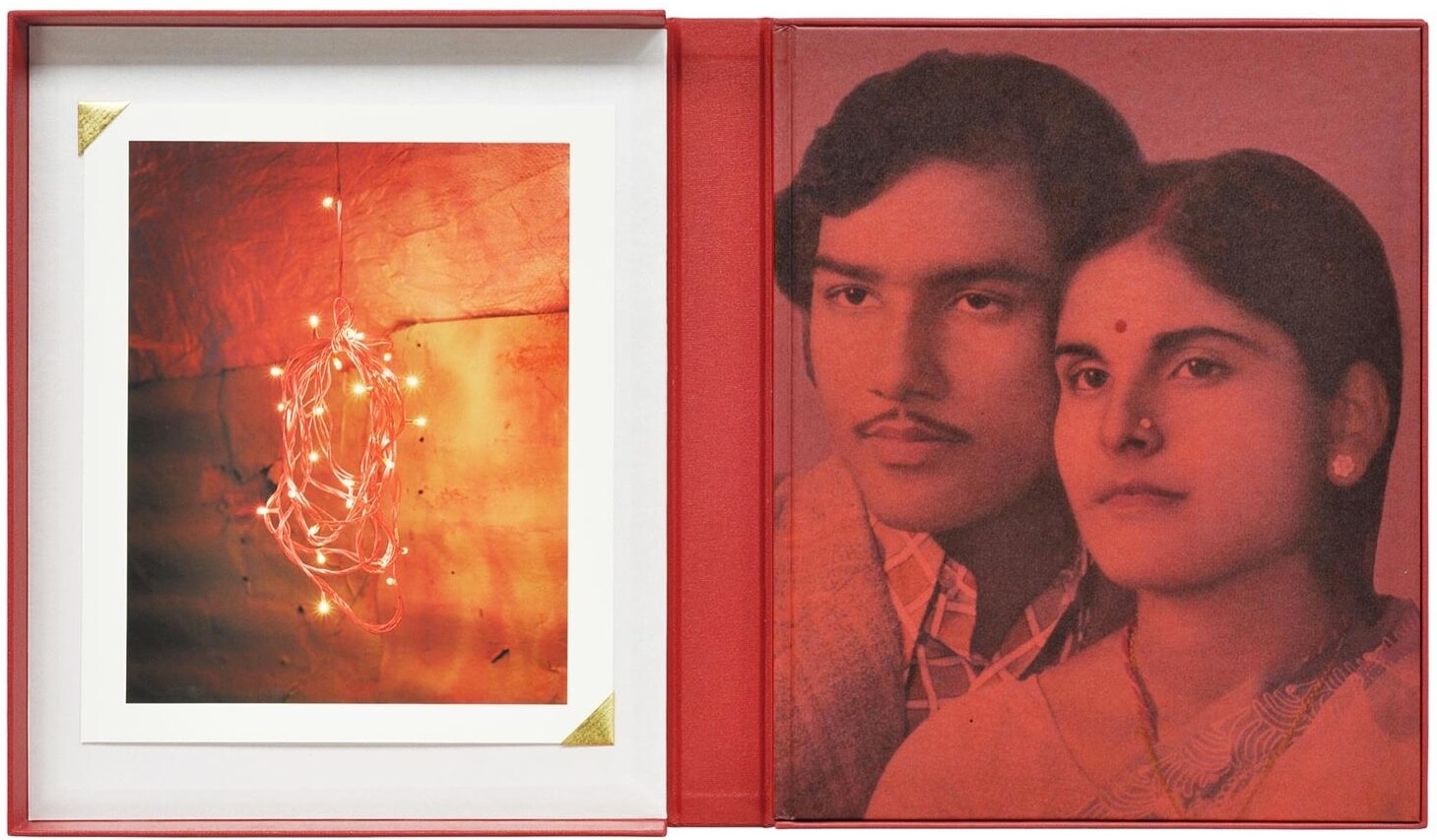

From The Promise by Vasantha Yogananthan, special edition.

KS: So here’s a big question, how do you turn a good book into a great object?

CPK: It may seem obvious but the relationship between the content and the design are one of the keys to making a good book. A great design can fall flat if it feels like it’s been overly done, and with not much reference to the work inside. Making a great object is about tactility, using a specific material for the cover, papers with a different touch or bulk inside. In the end, it’s all about experiencing the book, rather than just flipping or looking at the book.

KS: Do you ever think back to moments when the wrong editorial or design decision was made?

VY: If I had to reprint the first chapters of A Myth of Two Souls they are certain things I would do differently. The project has a raw energy to it: shoot, edit, publish and repeat. There is not much time to let things cool down in between chapters. But it is also the fun of it.

KS: How much do you learn from each book project, through what is successful and what could have been improved upon?

CPK: The learning process is always ongoing. I learn so much on every book, also because with every artist the overall experience is different.

KS: What have been some of your favorite design choices made for a CC publication?

CPK: For the cover, Shoji Ueda by Shoji Ueda is still my favourite. I love Astres Noirs by Katrin Koenning & Sarker Protick for how immersive it is and Behind the Glass by Alexandra Catiere for how meditative is is.

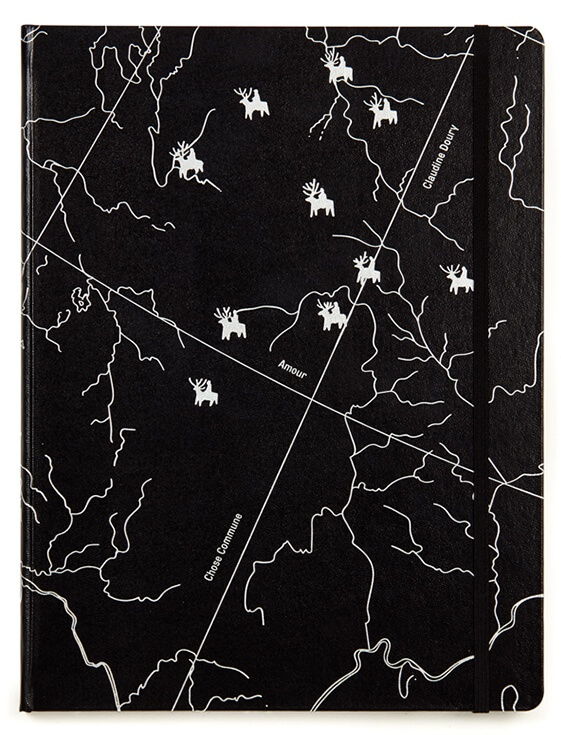

VY: Shoji Ueda by Shoji Ueda and Amour by Claudine Doury are probably my favourite covers. One of the strongest body of work we have ever published, including in its editing and sequencing, is Raymond Meeks’ Halfstory Halflife.

From Amour, by Claudine Doury

KS: I remember being introduced to CC through Vasantha’s ongoing project A Myth of Two Souls. The project offers a retelling of Hindu epic The Ramayana through photography and mixed media. I had never seen such an expansive ‘photographic epic’ before, and each of these books have been both distinct episodes and part of a cohesive story. They really do feel epic. As a publisher, it must be exciting and intimidating to work on something over the course of seven books. Can you tell us a bit more about what this process has been like for both of you?

CPK: It’s the most challenging project within CC for sure. Perhaps the craziest, too? For me, the process hasn’t been that much different from the other books, except for the pace and the numerous volumes. But I work the same way as I do with the other artists. I was only seeing the work when Vasantha was coming back from a trip, and after he had processed the negatives and scans. I never travelled with him to India on this project, so I somehow have a distant eye on the series, I am not attached to a moment or a photograph when I edit, I just do it with the same objectivity as the other projects.

VY: This project has led me to explore things within the photobook format I would not necessarily have otherwise. I am trying to create a body of work in which the readers feel a forward momentum from book to book. Because the project has been developed over seven years and countless trips to India I gave myself the freedom to experiment, make mistakes, go back, etc. When I was travelling I had in mind what the books could be – their dominant colour, their photo-text dialogue, their materials and layouts. Thus the book format has informed the picture-making process. It is quite different to shooting a project for several years, to figuring out what you have done and to ordering things into a book.

KS: How did it all begin and where do you see it going?

VY: It began as a documentary photography oriented project and it has evolved towards fiction. I was 27 years old and self-taught when I started. I was trying to understand the kind of pictures I wanted to create. After two years shooting in the same fashion, I eventually bought a large format 4×5 camera and I started to stage portraits with the locals. Three years in the making I got bored of staging things. I then bought a 35mm camera. The next chapter is shot entirely at night. I know where the project is going but I won’t reveal it. Sometimes people think I am only retelling the old story of The Ramayana but the series is not only about the possibilities of storytelling but the medium itself. The most important thing for me is to keep this project as a space to experiment different picture-making processes.

KS: Are there any logistical challenges to publishing a 7 book series in four years?

CPK: It’s financially very difficult to keep up with the pace and publish 7 books by the same artist in such a short amount of time. We did get some grants and private funds from a few collectors but the books were mainly all fully funded by CC, which is something we’re also quite proud of. There was no certainty the series would find its public when we first announced the 7 books.

VY: Between the trips, the post production, the editing and the sequencing it is a lot of work. Sometimes it was too much and I would get a bit depressed but Cécile was there to push me.

KS: When will the last two chapters be available from CC?

VY: Chapter six, Afterlife will be released later this year. As for Amma, the seventh and last chapter, I hope to publish it by the end of the year.

From Dandaka by Vasantha Yogananthan, the fourth chapter of A Myth Of Two Souls, special edition

KS: Moving on a bit, I wanted to talk about some of the other incredible artists you’ve published. Claudine Doury, Julie Cockburn, Coco Capitán. Could you tell us a bit about these projects and the artists who made them?

CPK: We publish a lot of other artists aside from Vasantha and there are so many stories to tell as it’s always different to work with every one of them. I first met Claudine Doury when I was working at Agence VU’. I’ve always loved the work she did in Russia and Siberia. When we learnt she was going back there in 2018 to make a third trip (the two first ones were in 1991 and 1997), we thought it would be great to publish a book that mixes the 3 periods of time, in the form of a diary. Regarding Julie Cockburn, I had been following her work for sometime, mostly at fairs on the stand of Flowers Gallery in London. I got in touch with them asking if she would be interested in making a book as there had never been a comprehensive monograph on her work. We launched the book in September 2019, coinciding with a solo show at Flowers Gallery. And for Coco Capitan, I’ve always been a big fan of her aphorisms and so I got in touch to see if making a book with a selection of those would be something exciting for her too. It was so much work for the both of us, she had to scan 10 years of notebooks, thousands of pages… I went through them all and we went back and forth, exchanging on our selection, sequencing the content so that there is a narrative when you read the book from beginning to end, although they are excerpts from different periods of time.

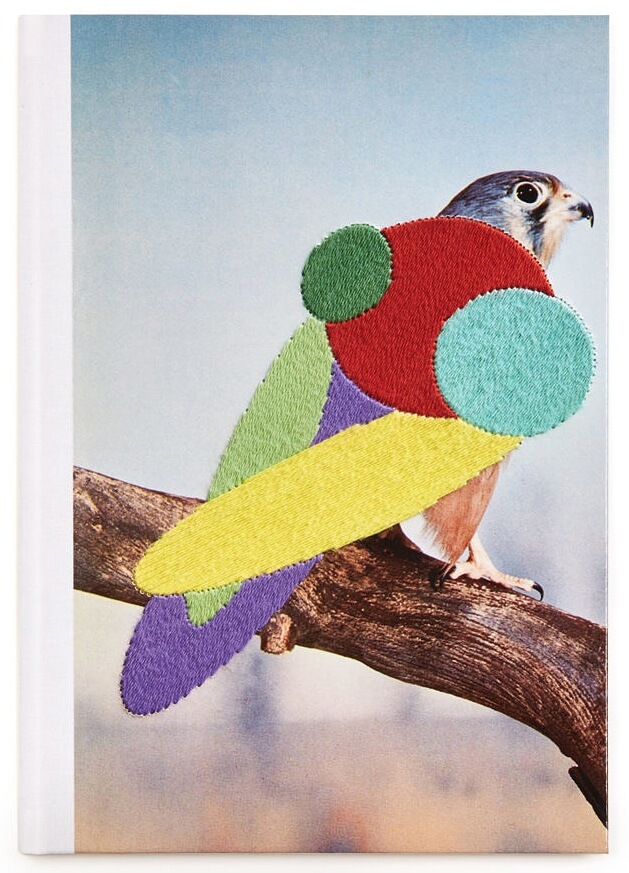

From Stickybeak, by Julie Cockburn

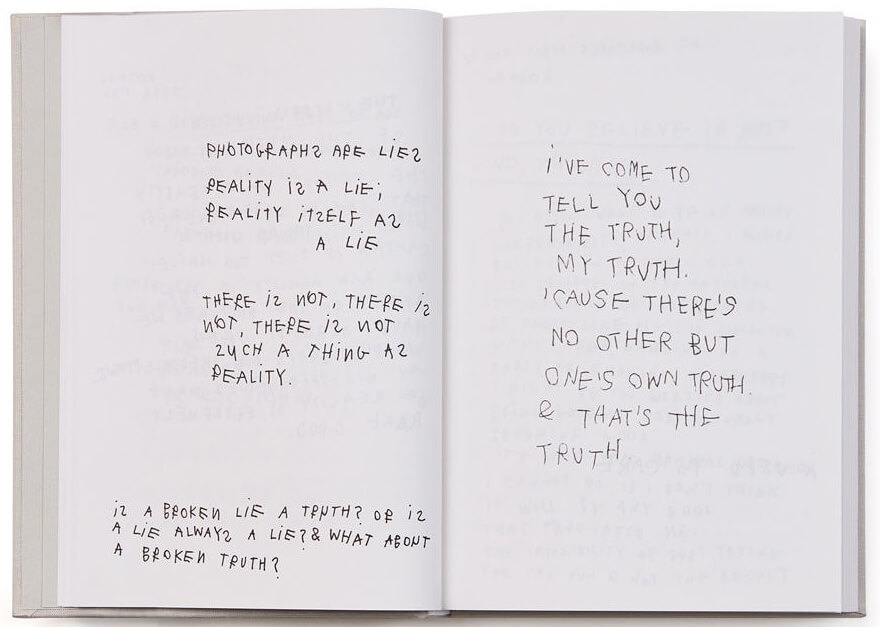

From If You've Seen It All Close Your Eyes, by Coco Capitan

KS: Where do you usually encounter work for the first time?

CPK: Everywhere, anywhere! Fairs, galleries, the Internet, on Instagram too…

KS: Are there any projects that have surprised you? Or emerged from somewhere unexpectedly?

CPK: Perhaps the project I’m working on with Stephen Ellcock at the moment. I have discovered his curation of images on Instagram and would never have thought we would work together on something one day. It happened because we share a similar vision on art and because he felt a connection to the idea I had for our collaboration. We will be co-curating a book together, coming later this Spring. The two of us have been exchanging hundreds and hundreds of images over the past few months, the process alone has been extremely rewarding and exciting.

KS: What usually draws you to a project, and what do you have to consider before publishing it?

CPK: The quality of the work of course, the personal vision and the story that’s being told. Before publishing it, we have to be careful that it’s not just a whim of ours, that there’s actually an audience for it and that eventually it can sell.

KS: So do you often find yourselves excited about a project but unable to publish it because you feel like the market’s just not there yet?

VY: The market is difficult to predict except for big names. Publishing the first book of a young artist is a great risk for an independent publishing house and we are proud to have done quite a few.

KS: What is it like working with these artists?

CPK: It’s enlightening!

VY: We have been lucky enough to be granted access to some invaluable archives, lately by the great Issei Suda. As a photographer, I learn so much by looking at vintage prints from masters of the field. With living artists I learn different ways of thinking about editing and sequencing and it is a great chance.

KS: I noticed you describe Chose Commune as being “in the fields of photography and works on paper”, and I’m just so fascinated by that description. Chose Commune has carved a real aesthetic niche with its innovative photography books over the years. Now with some of your recent publications, Andata-Ritorno by Nathalie Du Pasquier and Do Insects Play? by Johanna Tagada you’re beginning to branch out. Could you tell us about the decision to expand your creative bounds in that way?

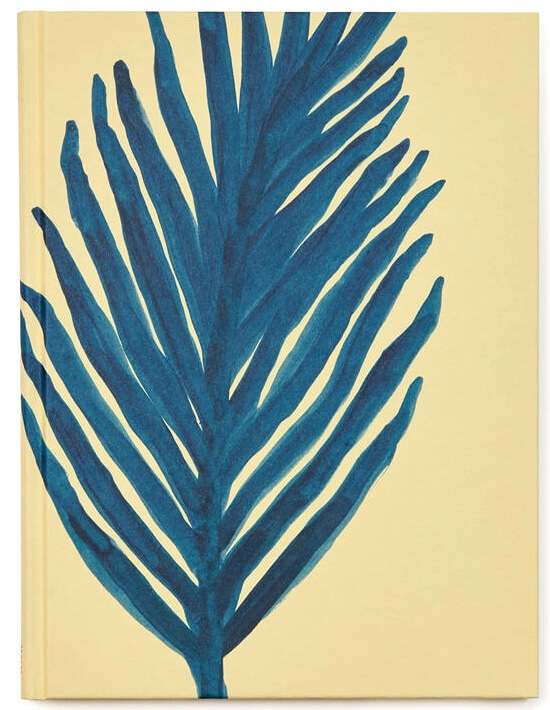

CPK: It wasn’t really much of a decision, it was there all along without people actually noticing it. Before 2019, we did only publish photography but the covers were almost never photographs. For Kito by Masako Tomiya, we commissioned artist Satsuki Shibuya to paint a watercolour inspired by Masako’s photographs… For Early Times, the first book of Vasantha’s series, we used a drawing especially made by Indian artists, etc. So it came quite naturally and appeared to people more clearly with Coco Capitan first, as it’s a text-only book, no images… And then the “coup de crayon” collection, which includes drawings and collages by Johanna Tagada, Nathalie Du Pasquier and Iris de Moüy so far.

KS: Do you find any differences between working with photographers and painters or illustrators?

CPK: The whole experience is very different, because their approach to the book is different. For a painter or an illustrator, the book will obviously be a reproduction of an original work so they don’t mind the interpretation of it. For example, Iris de Moüy and I struggled on the blue colour for her book Horses Are Blue. In her paintings, she was using a specific blue pigment from Japan that was impossible to reproduce. But she was fine with it, as the book is not the same thing as the original artwork.

KS: Does it feel completely new, or like a natural extension of work you’ve already done?

CPK: It very much feels natural as the choice we make for CC reflect who we are and what we like. And we’re certainly not photography freaks! I personally like photography as much as I like drawing, painting, sculpture, ceramics, woodwork… I don’t have a preference for photography, it’s just how it all started but I definitely don’t see myself as a photobook publisher, the term itself feels so narrow.

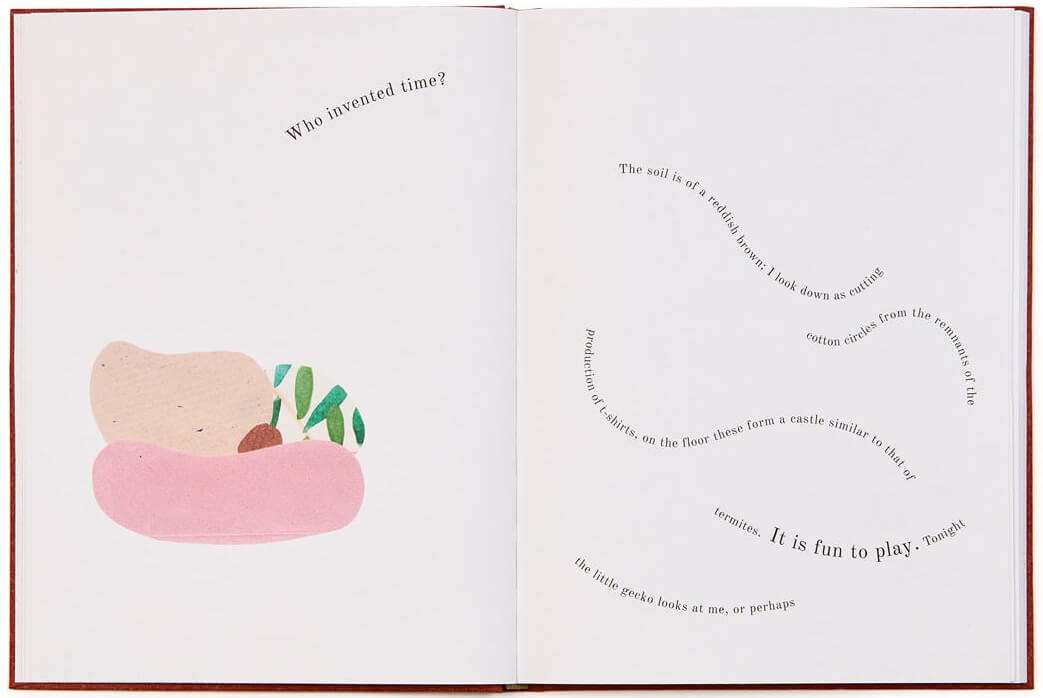

From Do Insects Play?, by Johanna Tagada

From Horses Are Blue, by Iris de Moüy

KS: Do you ever feel like the awards, fairs, lists, ect. make publishing photography books more challenging? Or do you find them to be more helpful?

CPK: The fairs are helpful as they’re a way of having your books seen widely. Awards and lists are helpful in the sense that they are rewarding for both publisher and artist, but they also make the competition grow and I don’t really like that. Some people only buy what’s on a list and it’s a shame, as there are a lot of books that just don’t get the same exposure but it doesn’t mean they’re poor quality, or not interesting. It’s so nice to find things by yourself too. I often think of flea markets, which I love, you feel so happy to find one thing you will really treasure and that no one else has found before you. I have the same feeling when finding a book I love – whether it’s online, at a fair or bookshop and I don’t care if no one has seen it, mentioned it and let alone given it an award.

KS: Finally, I want to talk a bit about the future of Chose Commune. Which projects are you preparing to publish this year?

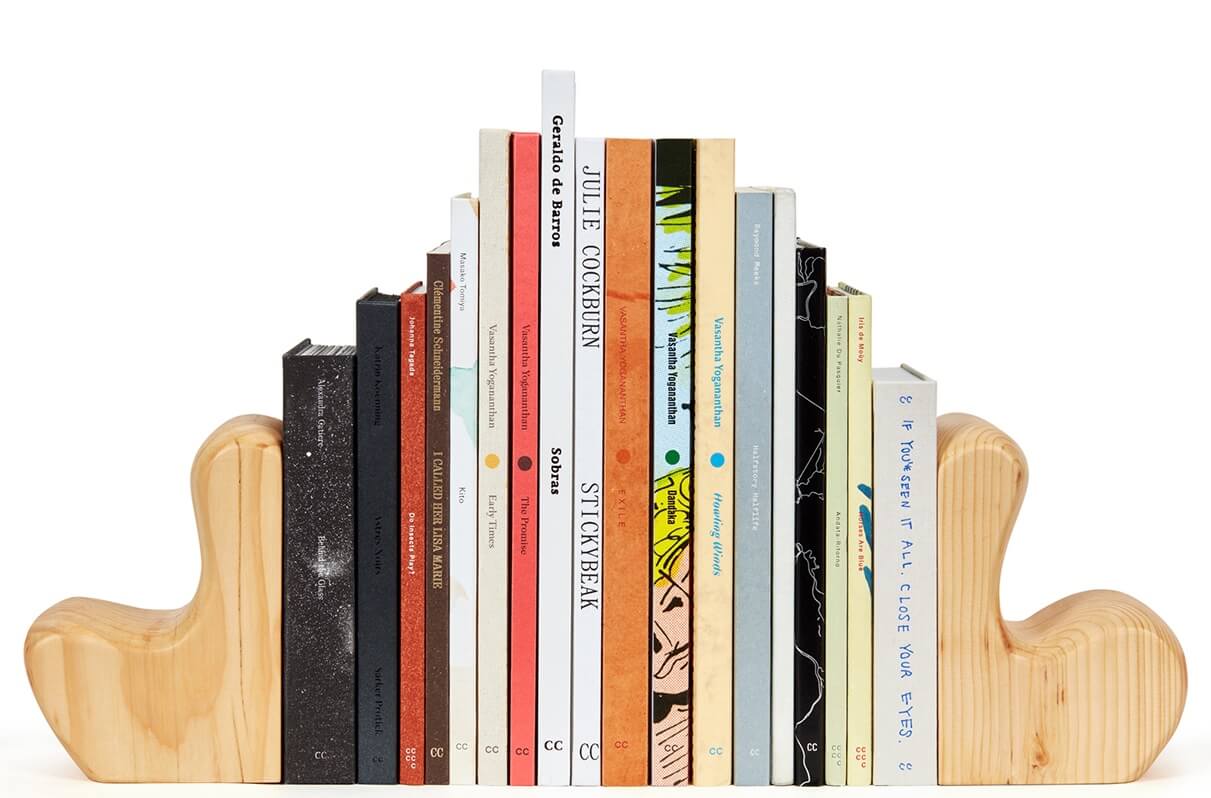

CPK: A lot of exciting projects for this year! A very Japanese year, too. A book with unpublished (and never exhibited) works by Japanese photographer Issei Suda that we selected among his archive last autumn. A book with unpublished drawings by Yoshitomo Nara, who’s making work especially for us. A new body of work by Rinko Kawauchi… The book with Stephen Ellcock I mentioned earlier and the two last books of Vasantha’s series… Since we founded CC in 2014, I’ve been 300% on CC, having absolutely no time for anything else. It always makes me smile when people ask me if I have a job on the side, or if I’m a designer working for other clients… As if it wasn’t enough to just be a publisher! But since I have some help now, I’ve been working on other projects for CC but not necessarily involving book-making directly. For example, we have just launched bookends that I designed in collaboration with a French project around woodwork and craftsmanship called OROS… I first had the idea as I needed some for presentation purposes on book fairs, but after working hard on them for about 6 months, we decided to commercialize them too. I am also developing other projects, doing curation and art direction as well as set design, under another label, septcils studio. I will be presenting some of this new work in a forthcoming website in the spring.

Affinités Bookends by OROS X Chose Commune

KS: Do you have any big goals for a future CC project?

CPK: More space to work, more time for the creative side of things. I’m very lucky to have an assistant 3 days a week now, who takes care of the orders, bookshops, press… This allows me to spend more time on the actual bookmaking and thinking of the next artists to publish.

KS: What do you hope the legacy of your work with Chose Commune will be?

CPK: I hope our books will inspire the future generations. That’s the really amazing thing about books, they will stay around forever.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.