Tealia Ellis Ritter on Oscar W. Ellis

Tealia Ellis Ritter (b. 1978) is a photographer based in rural Connecticut. Ellis Ritter’s work explores the intersecting roles of the photograph as personal document, familial marker of time and object with physical surface. Her work has been exhibited internationally, most recently by Aperture, The New Yorker, on Women in Photography, The Magenta Foundation, Catherine Edelman Gallery, by Taschen NYC and at Humble Arts “31 Under 31”. Her work has also appeared in many publications, including The London Daily Telegraph, Stella Magazine, Bloomberg Pursuits Magazine and The Financial Times of London.

Oscar W. Ellis (b. 1949 – d. 2004) was born in Hannibal, Missouri, and attended the University of California at Berkeley. Professionally, he was an engineer and CEO of a company largely focused on mining limestone. In his personal life, he lived as an outdoorsman and adventurer. He married an artist he met at Berkeley, named Anne, and fathered two children, Tealia and Crystal, who also grew up to be creatives. He was an avid photographer, a closeted artist of sorts, who used the camera as a way to record his life and the lives of his family members. His work has never been shown publicly… Until now.

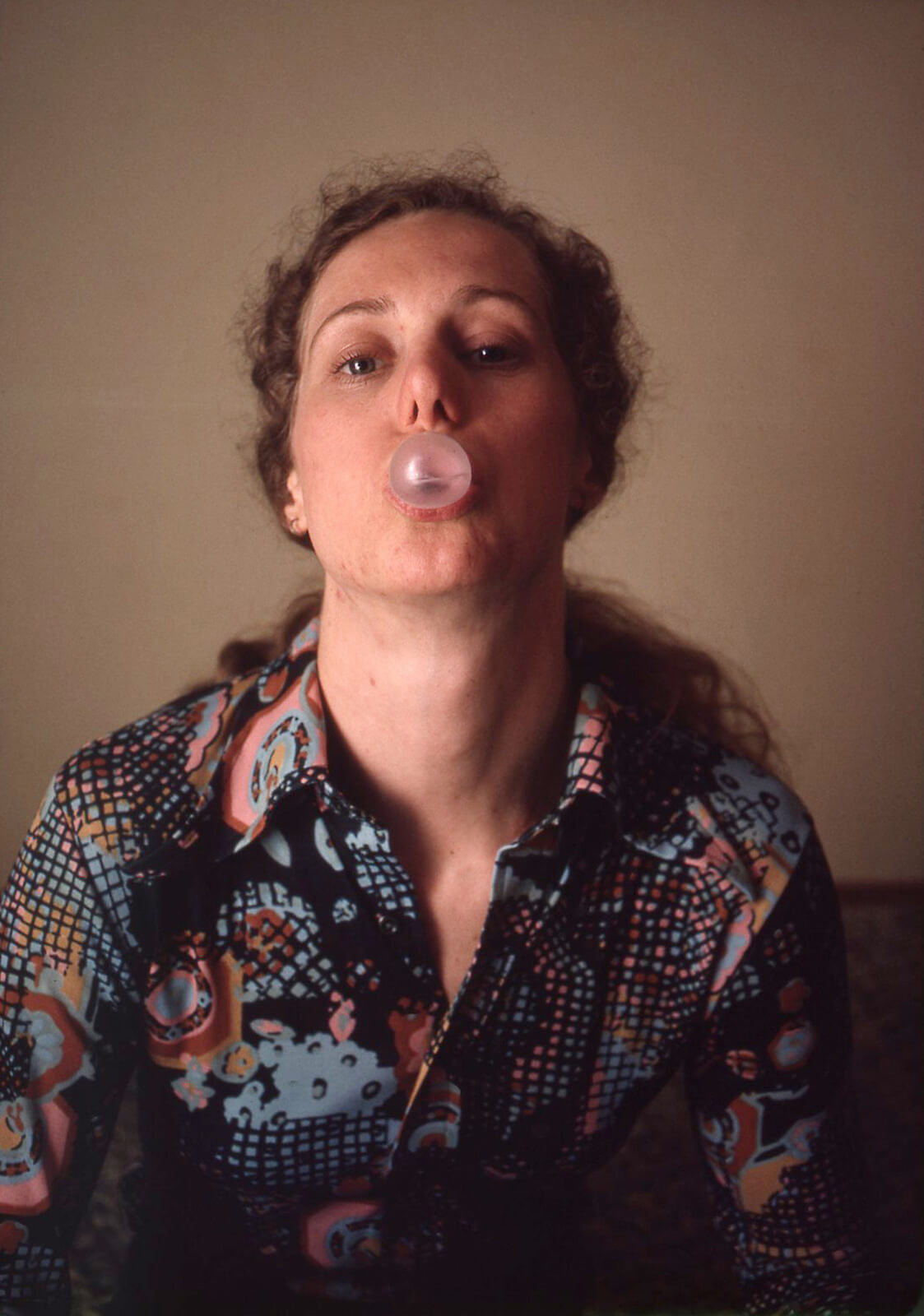

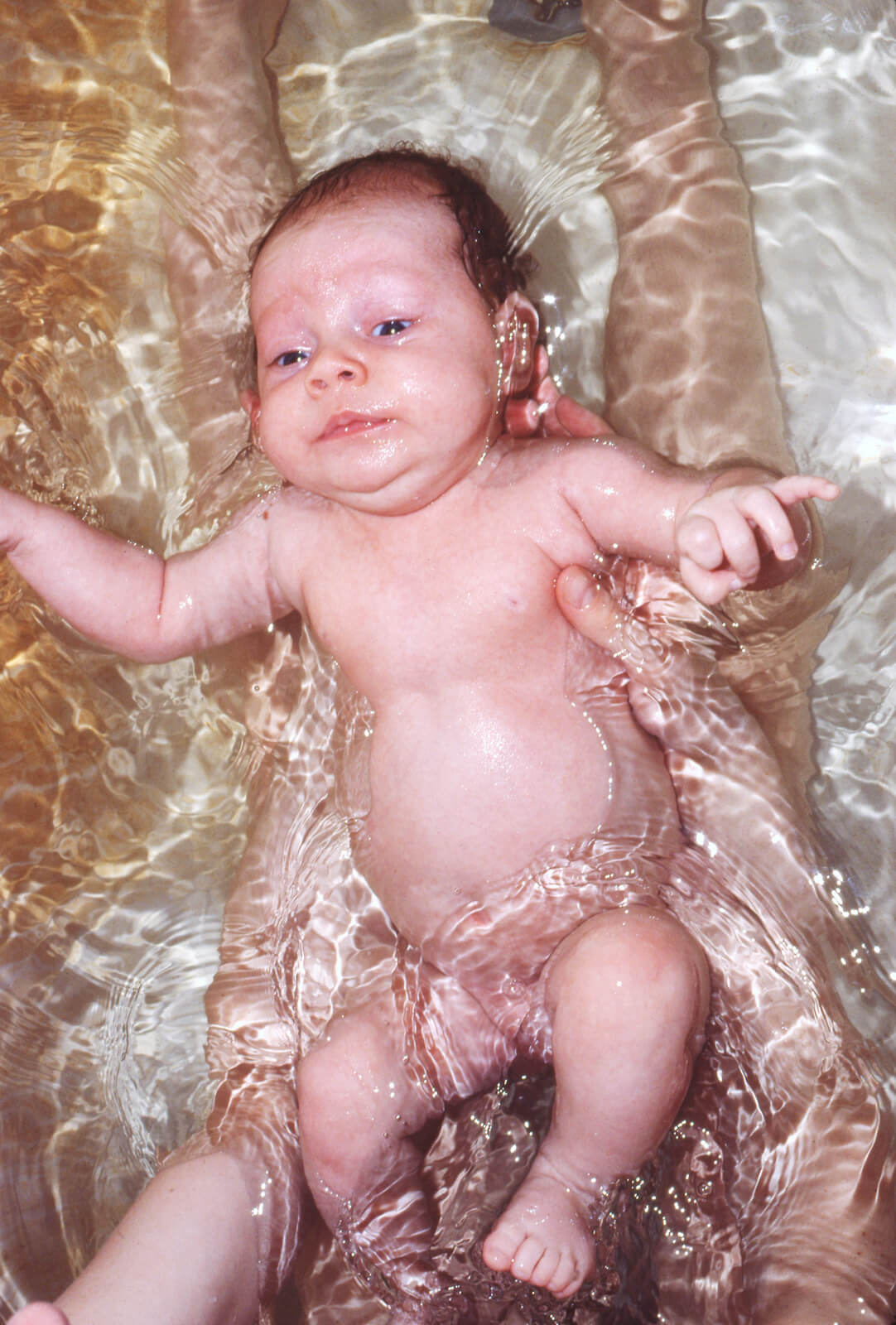

1: Oscar W. Ellis, 2: Tealia Ellis Ritter, throughout the article.

I can easily say that I don’t remember the first time I met my father and mentor, Oscar W. Ellis. I do however know exactly where the meeting took place; in the back bedroom of our small white farmhouse in East Moline, Illinois, where my mother gave birth to me as my father took her picture. There are few memories I have of our life together as a family that don’t include my father with a camera. The momentous and the mundane were equally covered. The moments you want photographed and the moments you would prefer to forget, as a child, were all subject matter in his eyes that ought to be preserved.

When I reached the age of six, my father gave me my first camera, a Canon F-1. He told me all I had to do was make the dash on the right side of the viewfinder line up with the center of the circle and then push the shutter. I can still see that circle and dash in my mind to this day. This gift of such an intricate tool to a child filled me with a sense of pride and a feeling of wonder that would begin to shape the way I would see the world. Most vivid in my mind though are the slideshows my father would put on for our family. They were his exhibitions. He shot almost entirely transparency film and so viewing his images always occurred in the dark amidst the purr of a slide projector. Our lives would flash before us in frozen saturated hues. In the still of the dark, everything we did seemed somehow more important. The gesture of a hand, the turn of a gaze or the bend of a body meant something when projected on a wall. It was in these moments that I began to view ordinary lives as worthy of examination and the family, a most basic tenet of human existence, as both pivotal and profound. This early thought process later drew me in art school to the work of photographers like Harry Callahan, Emmet Gowin and Seiichi Furuya.

Like my father, I did not see my images of family as my “work”, until a short time ago. His real job was mathematical and business oriented, the photos he took of us were part of an escape into something much more primal. They were a real thing that operated behind the surface that people saw at political events and board meetings. For me, I always photographed my family members but never showed the results, it was after all part of the routine that had been established. Even after my father’s death, from a malignant brain tumor, I continued the practice religiously but never thought the family images would be part of my work. Recently it occurred to me though that this is the only story that I alone can tell: a generational tale about a group of collaborators engaged in a fleshy life together.

As the keeper of the thousands of images my father created, I am inspired most by the breadth of what he chose to photograph and the sense of abandon and commitment with which he did so. I imagine that perhaps his lack of inhibition was due in part to the belief that no audience beyond our family would ever see the work, but I always had the feeling that he wanted to be acknowledged as a photographer, in some way, so perhaps he just saw no need to censor himself in images much the same way that he saw little need to censor himself in life.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.