Matt Eich in conversation with Beatrice Helman

Matt Eich is a portrait photographer, and photographic essayist working on long-form projects about the American condition. Matt’s work has been widely exhibited and received numerous grants and recognitions, including PDN’s 30 Emerging Photographers to Watch, the Joop Swart Masterclass, the F25 Award for Concerned Photography, POYi’s Community Awareness Award, an Aaron Siskind Fellowship, a VMFA Fellowship and two Getty Images Grants for Editorial Photography. He has three forthcoming monographs scheduled between 2018 and 2020 and is currently a Professional Lecturer of Photography at George Washington University.

Matt resides in Charlottesville, Virginia with his wife and two daughters.

Beatrice Helman is a writer and film photographer; she graduated from Barnard College in 2014 and is currently working on a MFA in creative writing, fiction, at The New School. Photography and fiction are forever interlocked in her brain, and her work explores the line between what’s real and the make believe. She lives in Brooklyn, NY and loves her parents.

Beatrice Helman: Okay so, first things first. Where are you from? Where do you live now?

Matt Eich: I was born July 11, 1986 in Richmond, Virginia and I was raised in Smithfield & Suffolk, Virginia. I’m currently residing in Charlottesville, Virginia.

BH: It feels like your family is so central to your creative center right now. How would you describe your family growing up?

ME: I am the oldest of four children, born to conservative upper-middle class parents, my father a cardiologist, and my mother an occupational therapist who stopped working to homeschool the kids. We grew up in rural areas of Virginia where I spent my formative years living on gravel roads, surrounded by woods, and animals.

BH: How does Virginia influence your work?

ME: I grew up in rural parts of Virginia, and almost always feel more comfortable being in, and working in smaller places. My threshold for large cities is limited, though I enjoy the energy that I can find in densely populated places. I naturally gravitate towards the edges of things, the peripheries of events, people or places that might commonly be overlooked.

BH: Were you an inside kid, an outside kid, or both?

ME: I read a lot, and played a lot of neighborhood sports growing up, wandered in the woods, went hunting and fishing with my Dad. I was definitely an outside kid, but an injury at 14 put me inside for a while, when I really got into music in a deep way. My love of photography has always been accompanied by my love of music. The two are intertwined in my head. I also met, and interacted with a lot of blue-collar Americans growing up in rural areas, and I’ve always been fascinated by their lives, and their stories.

BH: I’m fascinated by the connection you mentioned between photography and music – I’m a fiction writer and somehow my written stories and photographs always bleed into each other. Can you talk a little bit more about this, about how you interpret the relationship between the two? Do you ever create soundtracks to your photographs, or is there a particular album that has provided mood and aura for a particular project?

ME: Well, my first large project is called Carry Me Ohio, a title that comes from a song by Mark Kozelek of Sun Kil Moon. At this point, I know my abilities are primarily visual, so whenever possible, I love to collaborate with other artists. My friend Tyler Strickland has provided original scores for several of my multimedia/motion/installation pieces. I would love to delve deeper into music and visual collaborations, and include other audio elements in installations along with photos and video. Whenever I’m working on an edit or a sequence of photographs, I have music playing in the background that provides an emotional framework for the photographs. I try to create sequences that have the same sort of flow, or rise and fall, that a song may contain.

BH: Can you remember when you first started taking photographs? What was the attraction?

ME: I first consciously made photographs on a road trip with my grandfather, when my grandmother was dying of Alzheimer’s disease. It was around that time that photography sparked an interest for me, likely as a response to my grandmother’s deteriorating state. Photography became a means to find footing on the muddy road of memory. Early on I made bad landscapes, pictures of birds, flowers, and other animals. Occasionally I would photograph a family member. I continued photographing throughout high school and worked at a camera store. I would take lunch breaks and go look at magazines, where I was exposed to James Nachtwey, and other photographers making meaningful photographs of the world. This is what drew me to photojournalism, and to Ohio University where I began to make cohesive bodies of work.

BH: So when did you start thinking about getting into photography professionally?

ME: When I was in high school, I worked for the Ritz Camera store where I purchased my first camera after mowing a bunch of lawns. When I was 19, as a sophomore in college, I started freelancing for the local newspaper, The Virginian-Pilot. This led to internships, and other freelance work for a growing roster of clients, as my projects and portfolio developed. Prior to starting an adjunct teaching gig in 2017, which pays a poverty-level salary, the last time I had a steady paycheck was when I had an internship at National Geographic in 2008. I was 21 years old, and at that point I had a kid who was 6 months old. This is to say I didn’t have a lot of time to try things out before I needed to begin generating an income with my meager skill set, so I’ve been making the best out of freelancing for the last 12 years, always with an eye open for options that might be better suited for the intersection of providing for and being with my family, and making work.

BH: You mentioned memory briefly, and I just want to circle back to it and take the opportunity to address it. I wanted to ask about the link between photography and memory, and therefore, in a sense, history?

ME: This thread between all of them is the one I find myself returning to time and time again. Aside from an individual’s personal memory, which is very fluid, there is also the issue of collective national memory, which is equally fluid. This memory informs our sense of identity, our understanding of history, and therefore, influences our actions and reactions to other social and political stimuli. How photographs factor into this is largely beyond the artist’s control, but I believe it is a worthwhile topic to grapple with.

BH: Who are some other photographers you love and look to?

ME: Eugene Richards is probably the largest influence on my work. It’s his fusion of words and pictures, and his ability to depict strangers and lovers with the same level of intimacy that I respond to the most. I soak in a wide range of influences though, and my newest family work has drawn a lot of influence from Emmet Gowin, Alessandra Sanguinetti, Glen Erler and especially Larry Sultan and Doug Dubois.

BH: I definitely thought of Larry Sultan in relation to your work, particularly his tendency to make such personal photographs. Do you think the dynamic that exists between reality and fantasy in his photographs happens in yours too?

ME: In my previous projects, I am drawing from the documentary tradition and only stage or pose portraits. The family work is a shift in that I take more control of certain situations and stage or recreate family events, or things that I have seen, whereas in my other work, I just photograph what is in front of me, and don’t control or stage anything. Aside from his stellar photographs, and the intimacy of his work, what draws me to Sultan is his brilliant writing, which combines a self-effacing humor and vulnerability.

To the topic of staging… Well, typically I feel that whatever life has to dish up is more interesting than what I can imagine. If I have any interest in staging with my family work, it is rooted in reality (a previously observed occurrence), and I always try to allow for some slippage, or serendipity to occur, as a way of breathing life into an otherwise static scene. I’m trying to pay attention to that space between reality and fantasy though. Sometimes what I want to photograph is not what the photograph gives me, and the unexpected is often a gift.

BH: You’re a father and a photographer. What is the relationship like between those two?

ME: In an ideal world, the two could coexist. This does not seem like an ideal world. Once, as I was in the mode of making a photograph, my wife reminded me, “There is a difference between being a photographer and being a father.” For me the two are intertwined though. I can’t leave home and not carry my family with me in some capacity, it colors every interaction I have. And certainly at home, art and photography often have to take a backseat to the needs of family; the two are frequently at odds. Echoing back to the previous question about reality and fantasy – the lines between my life as an artist and my life as a father are blurry at best. Perhaps the fantasy (illusion) of life as a “successful” artist/father does not really exist. Perhaps I must choose between the two. If so, I choose fatherhood. But I do so knowing that photography is forever entwined in how I deal with life. Even if I walk away from making my living as a photographer, I don’t imagine myself capable of putting the camera away.

BH: Is it difficult to work with family members? Was there anything that you didn’t photograph, or something specific that you were looking to capture? There’s something so authentic and specific about your photographs of your family, while at the same time they’re absolutely relatable.

ME: Photography is always a give and take, so there are frequent times with family when I don’t photograph, but when the light is good, and family is together, and all seems to be going smoothly, I like to make a photograph. Sometimes when things aren’t going so smoothly, I like to make photographs too. These photographs become an important counterpoint to the stereotypical family album where everything is always sunny, and cheery. Most images stem from having a camera nearby, and always watching the way people interact with one another, and their environment. The ways in which we shape the spaces we occupy, and the ways in which the spaces shape us.

BH: What has drawn you to using your own family, over strangers, for the project I Love You, I’m Leaving?

ME: This work is a continuation of the family photographs I started making as a child, but more focused, and specific. I decided to photograph my own family for a number of reasons. One, I was photographing them already, and I was kind of burned out on photographing other people’s lives. Two, I wasn’t photographing family at the depth that I wanted … one that related to the depth of feeling I have for them. Three, it was a really difficult, tense time in my extended family, fraught with a wide range of emotions that I needed to reconcile in some way. This particular iteration of my family photographs began during graduate school, when I was in a pretty dark place personally. For better or worse, photography is the way I deal with most things. Still I’m always running up against the boundaries of what photography can do, in the way that I want to use it. Despite our intimacy, the people in my family will always be a mystery to me. There is only so much you can know about a person, and only so much that a photograph can describe. It’s all surface.

BH: I’ve always felt like houses are their own ecosystems that actually represent the big giant ecosystem. They’re where so much happens, big and small. What were some of the hardest dynamics of this project?

ME: Switching between father, husband, and photographer is always going to be difficult. For me though, these are the most rewarding kinds of images that I can make. Something representative of the emotional rise and fall of domestic life that is true to my experience, that will also, hopefully, resonate with others. Our house is a funny ecosystem, with four individuals who bring their own wants, needs, expectations, and mini-dramas to daily living. Exiting and re-entering the domestic sphere is the hardest part. The rhythm of dishes, laundry, trash take-out, bedtime feels comforting to me.

BH: Where did the name come from? It’s such a perfect link between two emotions and two thoughts that are bound together not only by the person feeling them but also the comma in the middle.

ME: The project went through numerous titles before I finally settled on one that worked. I wanted a title that was open-ended, but still loaded with potential meaning. I wanted it to address the fragility of relationships, of memory, and the friction of constantly coming and going from those you love. The series spans 2014-2017, though the majority of the work was created in 2016 and 2017. It represents a sliver of time in my life, and as such is a cohesive set of photographs, but it draws from something that started much earlier, and will hopefully continue until the end of my life.

BH: Can you talk a little bit about how this project relates to the the idea of fictional accounts that mirror reality?

ME: This gets back to our earlier discussion of Sultan, Dubois and others that have incorporated a sort of “staged-narrative” into their family practice. I’m a hybrid of portrait/observed moments, and interested in this space in between staged and serendipitous, and what that can yield. I’m always observing, and making photographs, but the structure of this series is inherently fiction. It is drawn from my life, but it is not my life. The photographs are of my family, but the photographs are not my family. Does this make sense? I want all of the photographs to strike a note of melancholic memory, a chord with enough resonance to contain beauty and sadness. A visual representation of how I felt during this time in my life – that’s the mirroring reality part.

BH: Is there text?

ME: The only text in the book is a poem I wrote, and an acknowledgments page. I thought about including more text, a statement perhaps, and I really wanted to start the book with a lovely quote by Nayyirah Waheed, but in the end, we kept the text minimal.

BH: Was it a choice to shoot primarily in black and white, or was it just what came naturally?

ME: The decision to work primarily in black and white makes a lot of sense in hindsight, but I have to admit it was a struggle to get there. I kept attempting to fit color photographs into the book, but it never really worked in the way I wanted it to. In the end, we incorporated two color photographs into the book, one at the beginning, and one at the end, printed and displayed differently from the black and white to set it apart. As we talked about before, I’m primarily a color photographer, so it took a lot of wheel-spinning to let go and commit to black & white for this work. Now that the project is over, I’m shooting a mix of color and B&W depending upon the situation, and my mood.

BH: What were some of the highs and lows of putting out a new book? How long was this in the making?

ME: The process of making a book is fairly grueling … You spend years making work, editing down to the core, then there are questions of sequence, design, text, paper stock, every little detail of how the book is bound, meant to feel, and there is a lot of cutting elements that are personal to you. It is still my favorite way to present photographs, however, because of the room for an expressive range that is carefully constructed for the viewer. I started working with the publisher in 2016, so it was at least a year plus in the making.

BH: What did you want this book to say?

ME: I really wished the viewer could find a piece of themselves somewhere in the photographs. Well-crafted images and words have the power of allowing someone to inject themselves into the lives, and emotions of others. The book is almost an invitation to read a family diary. My memories, your memories, our memories – our hopes, desires, fears … what do they share in common? Hell if I know, but I’ve come to accept that we all share more in common than societal structures would lead us to believe.

BH: Can you talk a little bit about what’s next for you, and this project?

ME: Multiple book projects. Feeble attempts at remaining sane. Trying to be home more often. I Love You, I’m Leaving was published with ceiba in the fall of 2017, and three additional volumes of The Invisible Yoke are scheduled for publication between 2018 and 2020. Each body of work has enough photographs to publish, but I’ll continue working on them, and adding to each project, until the publication deadline. In the spring of 2018 I am releasing a collaborative book with my buddy Jared Soares, called Days Before / Days After.

Recently I’ve been teaching, and I really enjoy interacting with hungry students, and thinking about photography through different perspectives. The hope is that teaching will allow me to be home more consistently, to be more selective about the work I take, but that hasn’t manifested yet. Currently it means that I travel each week for teaching, and often for the remainder of the week for commissions or project work. So, I continue to accept freelance work, apply for grants, sell prints … you know, the usual hustle.

Aside from that, I’m making new photographs for a series that I’m planning to continue through 2020. Keeping it loose for now and seeing how that develops.

BH: You have a newer series out, ‘Say Hello To Everybody, OK?’…

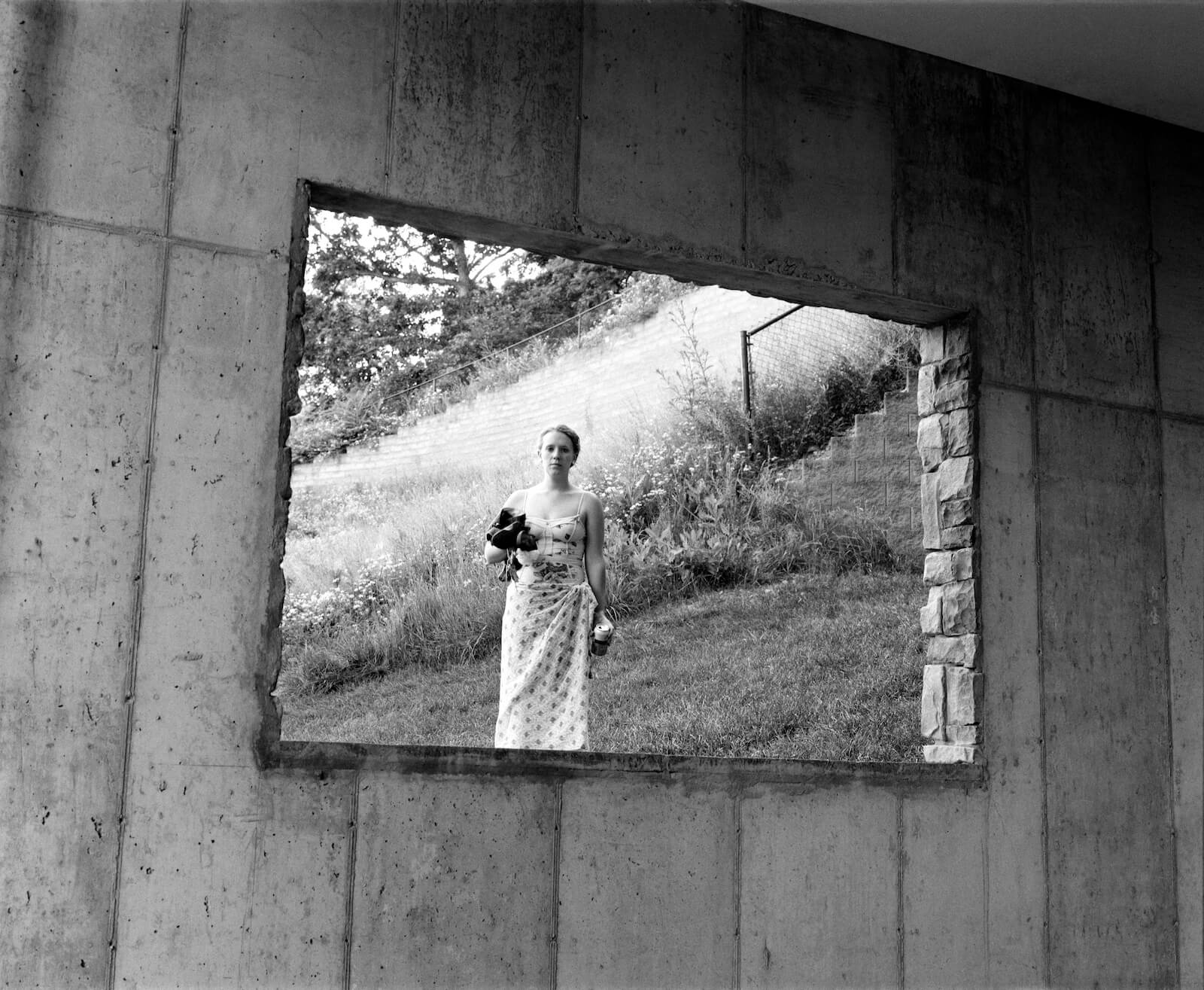

ME: This series is still new enough that I don’t want to put too many words to it for fear of boxing it in. The title is drawn from a quote by President Trump with TIME Magazine. The images I have gathered thus far come from a desire to express what I see and feel about my country’s current trajectory, and our increasingly polarized and fractured social consciousness.

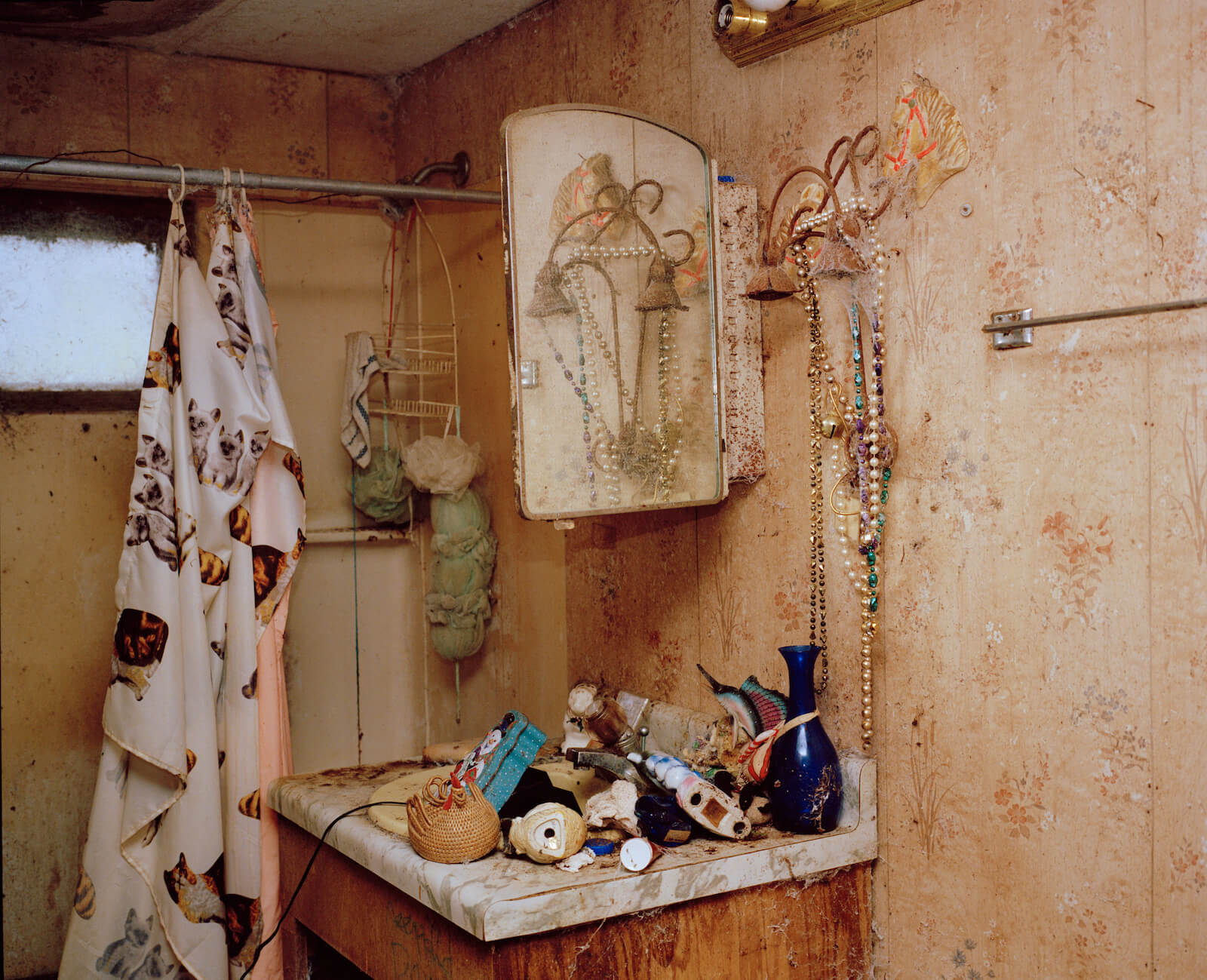

BH: These photos are so powerful individually and as a complete piece, and I was wondering what you saw in the relationship here between the people in the photographs and the space around them, which we see at times really falling apart in these photographs

ME: There is always this question in my mind about whether we shape the spaces we occupy, or do these spaces shape us? I think it is a little bit of both. I am drawn to scenes that reflect the battered and broken nature of our socio-political system. Themes from my previous projects, an interest in how our history and memory continue to shape our identity surface in this work as well. Things definitely seem to be falling apart on a daily basis in our contemporary society, so I suppose it is natural that I feel compelled to depict this visually.

BH: Can you share a story behind one of the photographs, say the one with the little boys at the baseball diamond?

ME: In early 2016 I was sent to Mississippi for a story about minor league baseball franchises. This image was from a little league game in Pearl, Mississippi that I photographed as part of this assignment. This image did not speak to what the story sought to illustrate, but it did hit an emotional note that I am interested in. Baseball is an American pastime, one that is embedded in our collective consciousness. Especially on the local little league level, it is an activity that many can place themselves in. The image is made at some remove from the characters depicted, a coach and young players. There is a tension in their expressions and their body language that speaks to how I often feel when making images. Wanting to be closer, to understand more, but feeling a sense of distrust and uncertainty.

BH: These photographs feel like they’re about so much more than just a project that you wanted to do visually – they’re speaking to much, much larger themes and issues — could you just talk a little bit about intention, in terms of the intention behind these photographs and also the power of intention, if that makes any sense?

ME: It is hard for me to think about this as a project yet. I don’t want to establish artificial parameters without an appropriate level of being lost, uncertain, and stumbling. On a basic level, my intention with this series is to make the viewer ask questions about contemporary America. Who are we, where are we headed, who benefits from pitting us against one another, how did we get here, what are we willing to inflict on others in order to maintain power? Aside from that, I’ve been thinking more and more about our country’s problem discerning fact from fiction. This is a social construct that parallels photography’s tenuous relationship with truth. Photographs are fictions (reductions of the world), but are often read as if they were reality. I’m interested in scratching at this more with the pictures as the work progresses.

BH: Can we pivot quickly to talking about what it was like going to school for photography? You received a BS in photojournalism from Ohio University and an MFA in photography from the University of Hartford.

ME: I was fortunate, and stupid enough to study photography in school twice, photojournalism in undergrad, and I recently received an MFA in photography. Vastly different experiences. One fostered idealism, and expected a certain visual mold, but was taught in a relatively nurturing manner. The other fostered cynicism, eschewing any mold, and was taught in the form of constant mindfuck, and occasional verbal beatdown. I’m really grateful to all of the teachers and classmates I’ve had the opportunity to study with, and feel like these experiences have challenged and shaped me, both personally, and professionally. It gives me a multitude of perspectives to consider and draw from as I am making work.

BH: You’re a founding member of the photo collective LUCEO. What is your relationship to collaboration and collectives?

ME: LUCEO was formed in 2007, the same year I was married and became a father. It is a cooperative of independent photographers, with six members at the time. We collaborated for five years on group projects, exhibitions, publications, gave out a student award, and much more. In 2012 I stepped down from LUCEO shortly before my second daughter was born to focus on family and personal projects. LUCEO continues to exist and make compelling work. In general, I feel it is important not to operate in a creative bubble, but to be part of a community of artists. I’ve been fortunate to have this at different phases in the form of cooperatives, classmates, and other artists that I live and work in proximity to. I am always on the lookout for creative community.

BH: Being part of a collective makes me wonder about your relationship to social media – do you find it inaccessible or that it creates community, or somewhere in between?

ME: Social media is one of those parts of the industry today that I find interesting, and infuriating, but I can’t distance myself from in a satisfactory manner. It’s the most cost-effective means of reaching a wide audience right now, but it is challenging to put your work out there without feeling inundated. At best, it’s a discovery portal; at worst it is an alienating echo chamber of self-promotion. I go back and forth, and will ignore my platforms for periods of time, though I know I should be more consistent from a professional standpoint. I just get burned out. Lately more and more I’ve been wanting to retreat from social media entirely. We’ll see how the rest of this year goes, I suppose.

BH: How do you usually try to stay inspired and not burn out? What keeps your creative energy awake?

ME: Mystery and serendipity keep me creatively engaged. Visually, I get bored when there aren’t any surprises. Very little of what I am assigned to do professionally gets to the level of intimacy and relationship that I want for my photographs to contain. That’s why I’m mostly interested in the slow-burn; watching life unfold over an extended period of time. Early on I was attracted to very traditional, linear-narrative photojournalism stories. Eugene Richards’ work moves me so much because he takes that framework and expands it, making it more personal, and less linear. I’ve certainly drawn inspiration and influence from seeing the ways that filmmakers convey complex nonlinear narratives in a highly visual way. Say, Soderbergh’s Traffic, or Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Amores Perros.

BH: You have this image in your series We, the Free, of an older couple kissing, and she’s wearing a yellow cardigan. It’s one of my favorite photographs of yours. It’s emotionally stunning.

ME: That picture is of my grandfather, Henry Eugene Martin, kissing his girlfriend, Anne Stultz. I was on assignment nearby and stayed with my grandfather, then in his early 90s, and I made pictures of him and Anne while I was there. They didn’t cohabitate, they kept separate homes and bank accounts, but they were in a committed relationship since the deaths of their spouses, nearly 20 years before. Anne in particular was very self-conscious of being photographed, and kind of put the kibosh on me photographing them, which really saddened me, because I think they had something rather beautiful. That image is one of my favorite photographs, because of its unselfconscious intimacy, and because of my relationship with my grandfather, and his unintentional connection to this photographic life that I have been given.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.