Jake Stangel and João Canziani

Born in Montreal in 1986, Jake lives in San Francisco and primarily works on his laptop in cramped airplanes and unremarkable hotel rooms throughout the United States and sometimes abroad. He found his true start in photography while documenting the first of three bicycle rides across America with a trusty Contax G2 and a less trusty 4×5 field camera from eBay that turned out to have light leaks. Jake transitioned from assisting to shooting in Portland around 2009 and is somehow coming up on a decade of shooting a mix of amber-tinged editorial and commercial work for clients ranging from Sauna Monthly to Chobani. His favorite color is sunrise and his favorite fruit is a peach.

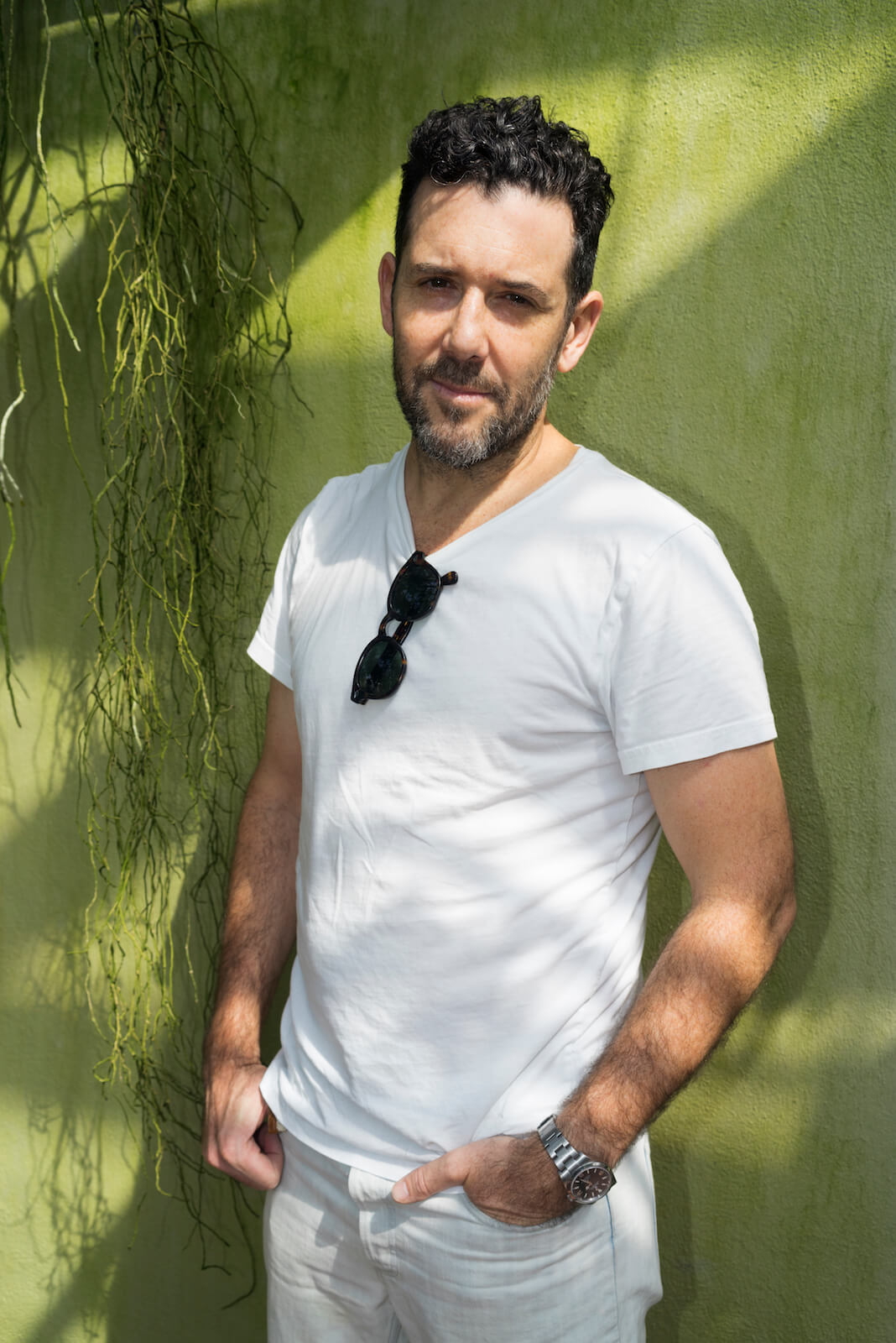

João Canziani was born in Lima, Peru. At the age of 15, he and his family moved to Vancouver, Canada. It was there that João first used his father’s old Pentax K-1000 to document the strange new landscape and get close to girls. After earning a degree in Psychology at Simon Fraser University in Canada, João pursued photography in earnest by moving to Los Angeles and completing a fine arts degree at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. Early in his career, João was named one of the “30 Young Photographers To Watch” by Photo District News, which immediately lead to frequent collaborations with magazines such as The Fader and Travel & Leisure, as well as commercial clients, such as American Express. Currently, João is combining his photographic and narrative acumen to tell stories on film. Recent projects include two short documentaries set in India, and a short narrative piece shot in Moscow, Russia. He’s based in Brooklyn.

Jake Stangel photographed by Amy Harrity

João Canziani photographed by Jillian Freyer

Jake Stangel

“The day I look at my camera as a moneymaker is the day I am done”

Jake Stangel: I thought it would be interesting to begin by looking back on 2017. I had an interesting one myself; you not only looked like you had an amazing year work-wise, but you and your lovely wife Jordan also had a beautiful baby girl, Paloma Canziani.

João Canziani: Yeah, that was the main event, that put everything in perspective. It was a very special year – job-wise, it started really hot, I was doing a lot of very good assignments, Verizon, and a few nice editorial shoots. Then Paloma came along and then it was summer. I heard it was slow for a lot of people, but for me, I really didn’t care anymore (how I used to freak out if weeks went by without the phone ringing!). It was really nice obviously to take that two-month break, thinking I was just going to be an “artist,” and have my daughter, and go work out or running and just do personal stuff… But it was a very, very intense two months. Having a child is no joke obviously, and no matter what people will tell you, your expectations will be blown off the roof. That kind of mellowed out, slowly, and I got back to work and I became a bit more focused, a bit more selective about assignments, because life took a new meaning… I was trying not to miss the beginning period of her life and I was interested in things that were good and valuable experiences to me, that would allow for me to grow as an artist, and obviously for financial reasons too, I was trying to support a third member of my family now…

JS: Did you talk to photographer peers who have recently had kids, like Geordie [Wood]? Did you feel remotely prepared for that new balance?

JC: Sadly, I haven’t talked to Geordie about this… I felt like all my friends and people around me were starting to have kids. We have a lovely couple who are very good friends of ours that live literally blocks from us and they had a kid a year before ours was born. We learned a lot from them, and a lot from other friends who have kids as well. So, I think we were prepared. But the encouraging thing is that a human being grows across a period of months and years, it’s not like a little puppy who’s suddenly “boom!” a full-grown dog and it’s done. It still feels as if I’m in some fantasy land, enjoying this very long honeymoon period of seeing my daughter grow into a lovely, lovely being. But we’re not yet dealing with the responsibilities of like, ‘Oh my god! we have to find a school for her, we have to set up an account…’ Or we have to do all these responsible things that you have to do for a human being. But those things are coming slowly, where you have to start thinking about insurance, about taking her to the doctor, all that kind of stuff. It’s not as overwhelming as I thought it would be, although the couple of first months were a bit tough, but I wasn’t working much, so that was alright.

JS: And now that you started working again, I’m curious to know, how has your relationship with photography changed? We’re in an interesting position because photography is both a creative outlet as well as the way we pay for the roof over our heads, the food we eat… There’s a pragmatism to it that I could imagine either goes way up, or way down, after having a child. It could either re-invigorate a dreamy sense of how you document the life around you or be a pressure point to really have to bring in the cash to help provide for a family.

JC: Well, I think on a very personal basis – just around the same time that Paloma was born, I was starting to think beyond photography. As a photographer, I started to think about film, about directing, or even about what’s happening about photography per se. Frustrations, all the shifts that are happening in the industry, photography becoming commodified. The prevalence of Instagram and how everything is homogenized. So, it’s still my passion and I still do it to validate myself, and to validate my life – I cannot imagine myself not being a photographer, not being a creative person. But to answer your question, it’s going a little bit beyond, I want to create things that are, I feel, a bit more about storytelling than just a series of photographs. What about your year?

JS: It does make sense. I definitely had the most odd year of my career last year, most of which was summarized in a long-form instagram post midway through the year, and the response to that really resonated way deeper than I ever thought it wood, which was heartwarming, and nice to understand that many people were going through a similar moment. Like you, the year started out strong, shooting for Amex at the same time that you were shooting that Verizon project. Then I went straight from Amex into a large project for Samsung in Montreal, then on to Amsterdam for Rapha and Telluride for T+L, and during those shoots, inquiries for future projects were coming in, things were buzzing like crazy, then each and every one of those potential gigs fell through, I came home and the phone almost entirely stopped ringing for about 4 months. And like you were saying with Paloma, one begins to have these external forces that affect your relationship with photography as a career, and it becomes as much of a focus to maintain the balance, you know? We all started out with photography being this incredibly pure, joyful, and creative outlet; anyone who is fortunate enough to turn photography it into full-time job needs to manage this balance between art and commerce. There’s such a gravity that comes into play when this creative service you provide is also what pays your mortgage, and then there are all the elements of legal and taxes and LLCs and bookkeeping, and before you know it, you’re running a business 90% of the time and shooting photos—the whole reason you became a photographer—sometimes as little as 10%. And I say this not as a complaint, but as central element of where my mind is at these days, and ruminating on how to reclaim some of the creative time I used to have more of.

João Canziani

JC: I completely agree. We went to Peru for the holidays and then once we were back, I really didn’t want to deal with all that stuff. I just wanted to take pictures and roam around and do projects and stuff. But having to deal with clients, and taxes, and accounting and all that… It’s crazy.

JS: I’m always cognizant of how fortunate we are to do what we do… I don’t have a commute, I’m my own boss, I get to travel. It’s absolutely crazy that we make our living by taking photographs. It still blows me away every time I really start to think about it. But going back to the 90% business running vs. 10% shooting thing: I was talking to a friend the other day about how to keep passion alive. These days, when I do go out and shoot, I’m aware of how sacred that is to pick up a camera. And I often think back to my Portland days from 2008-2011, when I was barely working or even finding work assisting, making 12K a year, my rent was $300, and pretty much all of my time was spent making images, building up a portfolio to try to get hired with. I was barely making any money, but my cost of living was so low that it afforded me the time to shoot endlessly. I was so hungry and excited, living on a shoestring budget and helming a simpler life. Tax returns were definitely easier. And sometimes, when I catch myself parsing disability insurance plans or brushing up on current California payroll and labor laws, I kind of pine for that past life. Lately, I think about how to straddle these two worlds: running a business and all that comes with it, yet at the same time keeping that kind of lightheartedness and that passion I have for photography. My greatest fear, and the place I will never allow myself to get to, is to looking at the camera and think of it as a tool that’s like “this is my work vehicle, this is how I make money, this is my job”. It’s absolutely necessary that the camera remains a vehicle for creativity and exploration. The day I look at my camera as a moneymaker is the day I am done. I look at bikes the same way: I don’t look at my bicycle and think “this is how I work out, this is how I stay in shape.” The bike for me needs to remain a vehicle to wander and explore; I try to keep that ‘lightness’ in my relationship with the camera as well.

JC: Right, it goes beyond a work-out, or a vehicle. It’s a way to make you feel human, in that physical and spiritual way. I completely agree about our cameras, such a noble way to validate us. We’re really fortunate.

JS: Extremely.

“It’s ok if I don’t get called, it’s not the end of my life.”

JC: Particularly now. I was reading the interview you sent me – there are so many kids coming out of school and looking up at us. I’m sure you probably thought the same way, but for me at least, I never thought I could reach this level. Not to say that I’m on top or anything, but it’s a fortunate thing that I’m finally able to make a living off something creative like this. That I’m able to travel the world, that I’m able to meet some amazing personalities and shoot them.

JS: Yes, I totally agree. That being said, the industry has shifted. Anyway, just going back to the whole thing about having lulls in your work, whether they last a couple weeks or months. I remember I was at a barbecue many, many years ago at Geordie’s where we talked about how to mentally cope with the slowness. A lot of people, at least in my circle of friends who are not in photography, think that it’s this kind of slow and steady trickle of work that comes to you. But I always thought of it — and maybe it’s just my luck – as a fire hydrant that’s either completely shut off or almost, gushing like 20 feet high in the air. And there’s never a much of a middle ground.

JC: I’m on the same boat and I think a lot of people are, too. When you wrote that Instagram post, I remember reading it and a lot of people’s reactions – there was one photographer who said “oh, I wrote a screenplay while I wasn’t working” and I felt, “wow, that’s remarkable”, it really inspired me… But the fire hydrant is a very fitting metaphor. It’s never a happy medium. You’re either thinking, “I can’t deal, I need to take a break!” or, “I’m going to shoot myself for not doing anything.” It became an existential crisis when I didn’t receive any calls and I often had this inner dialogue, “well go out there, shoot personal projects or something!” I often tried that, but there was often this uncomfortable pressure of doing something in order to fulfill a negative. It worked for a little bit, but for me – and I don’t know if you or other photographers feel the same way – I always needed this kind of weird validation from these other people to call me, to make me feel “relevant” again.

JS: Yassss. Preach.

JC: I’ve made my peace with that now. You know, most photographers – or any sort of artist really – want to have their work be seen by the outside world, and that’s the reason Instagram works, and pretty much everything else in this world works with social media. You may be a hermit and do your own personal work or live in the middle of nowhere – off the power grid – but for me, I still needed this communication, of being wanted by other people who wanted me to do these jobs. But long story short, since Paloma was born, that has changed. I almost don’t care, it’s a very weird shift… It’s ok if I don’t get called, it’s not the end of my life. It’s filled with other things. How has that changed with you?

JS: Well, going back to what you said earlier, it’s in part a sense of self-validation, but it’s also a bit of pragmatism. For nearly any freelancer or business owner, your work kind is your life. If you’re a restaurateur and people aren’t coming to your restaurant, or if you’re a plumber and people aren’t calling you, there’s always going to be that sense of “why aren’t people calling me, what am I doing wrong” per se.

And for photographers, there’s this element of, I mean—if you’re a restaurateur you think “maybe I’ll switch my menu” or if you’re a plumber you’d go “I need to advertise differently”—but for photography, it becomes “is it the way I shoot, and are people no longer interested in that?” I think that’s a really difficult mental process to wrap your head around. And I had a solid four months of that last year. The calls stopped coming so quickly that I was so confused as to how that could have transpired. And when your life and work are so intertwined, it starts to affect the way you think of yourself and your literal place in the world, how you know to contribute towards the forward movement of society.

JS: I’ve always made a huge effort on decoupling photography and my personal life. I think it depends on your creative process. I have friends for whom photography is what they live and breathe and eat and sleep and drink and it’s so intertwined. Like Thomas Prior, I’ve never seen him without a camera by his side. We got dinner years ago in Tribeca with Ben Grieme, and on the walk from the restaurant back to the subway, Thomas whipped out this little point and shoot and was taking these epic long exposure night skyscraper shots, whereas I would have just walked to the subway, looking down at the street, not thinking about photographs. And there was something phenomenal about seeing that level of complete dedication to his craft. I have a lot of admiration and respect for that. Plus, Tom is the biggest sweetheart and most earnest dude of all time. And Daniel Shea, I see him in his work, in these stupendous bodies of images he puts out into the world.… It’s his identity. And to look at their work, sometimes I feel like I’m this unworthy schmuck wearing Crocs over here in the corner.

Photography used to be my identity, but in recent years I’ve veered into other territories. Cycling has honestly taken over that a lot. If I had to identify as a type of person, I would consider myself more of a cyclist than a photographer these days. That’s given me a healthy outlet because if photography is low, it doesn’t affect me quite as much. I don’t give myself over to photography the way I used to do it in my twenties. I think in part it’s to protect myself, and partially because I’ve discovered passions outside of photo. My interest in photography has not diminished, I still care deeply about each shoot I do, and not feeling like I’m ever phoning it in, in the slightest. But it helps me, so that if commissions don’t flow, it doesn’t drag my whole self down. I feel more balanced, and more autonomous.

JC: I completely agree. I look at Tom and how he puts out so much work out there, it’s like 24 hours a day! It’s all he breathes, and it makes me feel a little guilty. I strive to do that, and I do it a little bit, but you know, I have a wife, I have a child, and I’m starting to have other interests.

JS: And that’s ok too! I think it’s healthy to learn what you need for you and only yourself. For the longest time I thought I needed to be putting out work 24/7, but it never felt like true me. I think it’s a healthy part of discovery to recognize you don’t need to do that if that’s not in your character, and if it is, that’s lauded as well.

JC: I almost wish that Kyle [R.M. Johnson] was in this conversation as well, because we’ve had so many rants about photography, and we feel empowered by these conversations. It’s a frustration that has been building up in me about this industry, about photography itself, about putting out work.

JS: I think it just comes down to finding a balance. And you and I are at this point of very much trying to find a balance between maintaining a deep passion for photography, yet also dealing with a photo industry that increasingly wants so much more for so much less, in a way that sometimes feels painful to know someone wants quantity over quality. In my mind, that’s the downfall of everything.

Right now, we’re seeing it throughout the industry… this tremendous collision between the death of print, the rise of digital, a radically transformed advertising landscape, and a complete proliferation of photographers — ‘Instagram’ and otherwise — entering the market. Then you combine that with it being 2018 and a general lack of decorum and civility in the world… You get a new photo landscape where now sometimes your clients have little real world photography experience, pulling together their mood board from a couple half-million dollar shoots they found, unaware of what it took to made it happen, and have none of the budget they need to pull it off. So there’s a disconnect from reality that falls on you to either sort out, through education and re-orienting what’s possible, or you walk away from the impending storm. And keeping your optimism when this is the new normal is something that’s tricky but important. At the same time, looking from the outside of this conversation inward, it’s essential to recognize that we are in such an insanely privileged place to be full-time photographers who can support ourselves comfortably. That’s something I try to keep in the forefront of the conversation and in my own mental space, that sense of eternal optimism. I’ve got no respect or patience for folks pulling in six figures but can’t find a single positive thing to say about this industry or the life and opportunities it has provided them. It’s ok to be frustrated, to want people to be better, as long as we keep perspective on being grateful to be here in the first place, because I will never forget the feeling of scrambling up the wall from the other side. There’s this infinite balance trying to retain this special effervescence to what we do but it’s also rooted in this very practical side of things, being on the phone, on email, on laptop all the time. Anyway. I digress…

“I felt a little guilty for thinking – am I here just for chasing the money?”

JC: Being in this industry for a few years, I think we’re kind of identifying what are the endemic problems of this industry, and in turn trying to survive. There are big shifts going on. What clients are asking for, they’re asking for the world. I feel we’re trying to look a little beyond, to the other side of that fence, to make sure we can be a step ahead. So I think it’s also a healthy thing to think of it this way, and not have all your eggs in one basket. Right?

JS: Yes, definitely. And I think it’s the natural kind of impulses, you know. If you’re in a situation where you feel like there’s more out there, you try to figure that out. And I’ve had many talks with many folks, given this tectonic shift in the industry, both in editorial and commercial. I say this with the caveat that I’m really truly grateful and aware of how good most photographers have it. I have the luxury to be talking to you at 11 on a Wednesday morning right now. And I’m not working three different shifts at three different jobs and supporting a family and getting paid minimum wage. So it’s paramount for me to keep that all in context and to remember that. That being said, with editorial, I’m increasingly getting assignment requests where I would be losing money to make the assignment happen. The rates are often getting so low that it’s becoming a constant game of limbo, like the budgeting folks are saying “well, we offered X amount for flat rate last year and let’s see if we can drop it by $200 or $300 and see if the photographer takes it”, and then next year it happens all over again. I’d be curious to hear the perspective from the photo editors side of things, because the magazines get thinner, ad sales go down, and something has to give, and I understand that. But at a certain point, you end up working for next to nothing, once you pay out your assistant at the rate she or he deserves, rent equipment, do all your production, etc, etc. I’m in a fortunate position to no longer have to say yes to every editorial assignment that comes into my inbox, but when the rates are low to the point of maybe losing money on a job, I will turn it down on principle, primarily because I don’t want to signal to a client that that’s ok to work for free or at expense. I know it’s common in fashion work, but I’m no fashionista and it’s just not a business model I subscribe to. It’s a crazy freakonomics thing where photographers are hired for the exact same level of work output, sometimes for a couple hundred dollars and sometimes for many thousand; I don’t know any other industry like that. But when a budget comes in unrealistically low based on the ‘ask’ (like three lighting setups in 30 minutes, but no budget for lighting or assistant), I always work it back to where it should be because I’m trying to make the best content I can make for the magazine. It feels very odd to get short changed in creating the content that makes the magazine the magazine.

JC: Well, I’ve had such an internal debate about that. I also very much agree about turning down some of those jobs but I’ve had past instances where I turned down a job shooting an athlete because of a low budget issue, and my agents were behind me in this decision, because we all need to make a living so it’s wise to keep the calendar open for more profitable gigs. But then I saw another photographer shoot this same athlete, and he did a beautiful job. I thought: “Ah damn it, I really could have done something cool with this guy too!” I felt a little guilty for thinking – am I here just for chasing the money? I understand having a principled position about this, but I think there’s this survival thing happening where we’re left in this weird jungle sort of environment, and we need to start learning what we can say no to and what we have to say yes to. I’ve taken assignments at the end of last year where it was $950 here, $750 there. Then another issue I’ve encountered is having to fill out some paperwork for an European editorial client in order to avoid getting taxes deducted from the respective European country. On a low, flat budget this can be a big chunk, and filling this paperwork out takes half a day plus having to get a form from the IRS. After all that and then not getting paid for months, you’re really not doing it for the money, but the love of shooting something worth it. The bottom line is, I would take an assignment that I think would be creatively fulfilling, that will benefit me in terms of images, portfolio wise, where I can get something really good, irrespective of budgets. Hell, I would fly somewhere on miles if I have to. It sounds kind of selfish but ultimately, I need to feed my soul, my creative soul.

JS: I don’t think that’s selfish at all.

JC: I don’t know. I was one of the first people to say: “Oh my God, you can’t take that job!”, or “What about these kids who are taking these jobs from under us, they’re undermining the whole industry!” And then I’m doing the same thing, a few months or years later.

JS: For me, we’re approaching this is as an equation where you need to figure out where you want to stand, and what at the end of the day is worth it for you. As you said, I’m fine to work for very little money for smaller magazines if I feel like there’s a lot of heart in the publication, if it’s a scrappy and passionate affair with infinite creative freedom but no financial backing. But it’s really hard to get told by Levi’s that they have $1500 all-in for a city shoot with perpetual usage and rights, and at that point, I’m like “I can’t be complicit in this model”.

JC: Well, that’s the problem. I used to work for the Fader when I started my career for $350 or $400 a shoot and it was awesome. But now the Fader has become a much bigger magazine and maybe their budgets have increased slightly. Also, Time Inc. and Conde Nast and other big magazine publishers are all kind of following suit with similar assignments that are web only. I’ve worked for those, I’m guilty of that. I’ve said yes to those assignments. I still think, though, that as a photographer you can still push for stuff. One thing I’ve gained these past few years is confidence. The confidence to not accept things for what they are, to push for those budgets and to be vocal in ensuring everyone involved in the shoot has their act together, from photo editor to photo assistant. I’ve had assignments where I’ve gotten paid next to nothing, yet production was very disorganized. I’m going out of pocket, paying assistants extra, upholding my end of the bargain, because the bottom line is, my reputation is on the line. In the past, I would have felt responsible for circumstances beyond my control, sometimes even for the weather, because on a travel job, you need to come back with something. But now, I’ve learned to separate myself from the situation. It still bums me out, of course. But I’ve learned to communicate, to explain what’s going on, and have a dialogue with the editor. I think respect is gained from that, rather than always having a blanket response when you’re asked how did the shoot go: “Oh yeah, it went great!” and that’s it. You should be truthful. There is confidence gained when you know you know you are respected as a photographer and you were hired because they liked your work.

JS: It makes a lot of sense. I like what you said about communication. I want to do the very, very best I can. The best jobs have good communication and mutual respect, with a photo editor who’s done the job really well and given the photographer the tools for success, and me being prepared and having the tools I need. I really take that seriously and give myself no leeway there, in terms putting it on myself to be on time, prepared, and ready for literally anything. And that’s when I feel the best about an assignment, as opposed to when I feel I was contacted because I happen to live in the right place and the photo editor doesn’t care and they need a warm body with a camera with a low day rate. The best assignments I ever had were the ones where I felt I was working as a team with the photo editor, making the best possible images for the magazine so that the magazine looks as good as it can possibly be.

JC: Everybody wins.

JS: Turning the corner here, I was talking to Geordie about the other day, about how we make all this work, we put it on a website, but in terms of actual dissemination of the work, all I’m really left with these days is Instagram. Tumblr was huge a number of years ago and I feel like no one really goes there anymore. Instagram, at least for me, and for many other people, has become the only platform to share projects, or at least to lead people towards your site. It’s like your bullhorn of saying “Hey, I have new stuff, you should really try to get over to my site”. You put a lot of effort into making the work, I view it on a 21” monitor at a hundred percent zoom, I know it intimately, see all these details. And then then they get swept across this tiny, four inch phone. And so it’s made photography something you quickly scan and move on from.

JC: It’s so frustrating! I don’t think people are even visiting your site. And I’m guilty of this as well. At night, before going to bed, I’m just scrolling through Instagram again. If I’m not actually shooting that day, I’ll probably would have been on Instagram 10 times by the end of the day, just because it’s so easy to visit it, and it’s the first thing you can do. I have to consciously think “Ok, I’m not going to go on Instagram today, I’m going to check the New Yorker, or pick up a book.” I’m trying to get better at this.

JS: That’s one of my New Year’s resolution, to be on the phone less. I think Instagram is kind of harming my relationship with photography. Even my brain wiring now, how I think about photos, how I ingest them. We’re looking at photos, but it’s almost a boredom now. And it makes the photos easy. I’m worried about making photos that feel like they’re meant to be processed quickly. I always joke that ‘a sunset gets a thousand likes’; Instagram fosters a visual culture where you’re encouraged to move on, to not dwell. Which is the opposite of the experience that I have at SFMOMA where I get lost in the minutiae of a Garry Winogrand streetscape for a couple minutes, or the leathery texture of someone’s back within an image of my favorite Rosalind Solomon book. At museums, I’ve noticed that it feels weird, different, to look at work for so long, which used to be my normal amount of time. I think we’re societally hitting a wall in terms of the amount of content we can look at for the shortest period of time possible. It’s just something I’m ruminating on. And I was talking to Geordie about it, it’s so funny to put your heart and soul into a project and it literally passes across someone’s screen for like, 0.3 seconds, pending an algorithm even making it there, and then it gets lost into the ether.

JC: It makes me think about the making of a movie. It takes a year to write a script, it takes so much time in pre-production and then 40-something days of filming and then a lot of editing and then we watch it in two hours. And we’re like “Oh, I didn’t like it very much”, and we move on to the next one, just to digest it. Instagram and social media have become a really bad way of doing this to images and all the hard work that goes into it. The ‘likes’ fuck with me, as I’m sure they fuck with everybody even though it sounds petty and childish. Why am I getting 175 likes for this landscape when a similar landscape by another photographer might garner 400 likes and then some other photographer’s gets 4000? You get into this rabbit hole and it starts psychologically damaging you. That’s why I started doing those Instagram stories, because you’re not able to press ‘like’ on them. I’ll just be able to see who viewed them, then maybe I’ll get some comments and that’s very nice. It’s not even edited. It’s just this regurgitation of life that’s kind of nice to show, as long as you exercise restraint. As with posting anything on social media, it gets annoying when you start obsessing about it and document every minute of your life instead of actually living it. But the nice thing about Instagram stories is that it gives the choice to the viewer, rather than seeing your zillion posts on their feed. But I’m sure all this is going to change.

JS: I think more, right now, personally I think I hit a wall. I think about this a lot, maybe more than I need to but, I think Instagram can be very visual for people, not even photographers per se, but people who know how to best describe something via an image and people who know how to understand something through an image. For me, Instagram is, on many points, still a very lovely, exciting and engaging medium.

JC: Yes, we love it!

JS: Sure, and in some ways I don’t have a vast amount of guilt or trepidation about engaging with it. But I’m starting to have issues with the ways it’s rewiring my brain – I guess, not so much the medium of Instagram, but it’s my behaviour with the app, and also what they push on me. If you’re making all this work but then, how do you better share that? It’s kind of the only way people are able to easily check in. Most everyone I know is done with Facebook. For a lot of photographers, from the marketing standpoint, Instagram is a bit of a life line but it’s also this thing that I think is damaging photography more than we might understand at this point. Personally, I’m more interested in reading and creating more long-form writing again. Almost in a way, the theme of this whole conversation is this notion of actively finding balance in all these realms we’ve been talking about.

JC: That is great. The older I get, I’m finding that too. It’s just not all about photography as an industry. I’ve rarely been like that, except a few years back, when I was new to New York, photography was all-encompassing, but it has since cooled down. Now that I’m married, and I have a daughter, other things start taking precedent. The beauty of this balance is that I very much identify myself as a visual person, as a photographer, you can’t take that away from me. Yet I don’t necessarily have to have all photographer friends, or always be looking at photography books, or always have my camera on me. Instead, it’s a sort of an unspoken religion for me, in a way.

JS: That is so true, Joao. Let’s go make a salad.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.