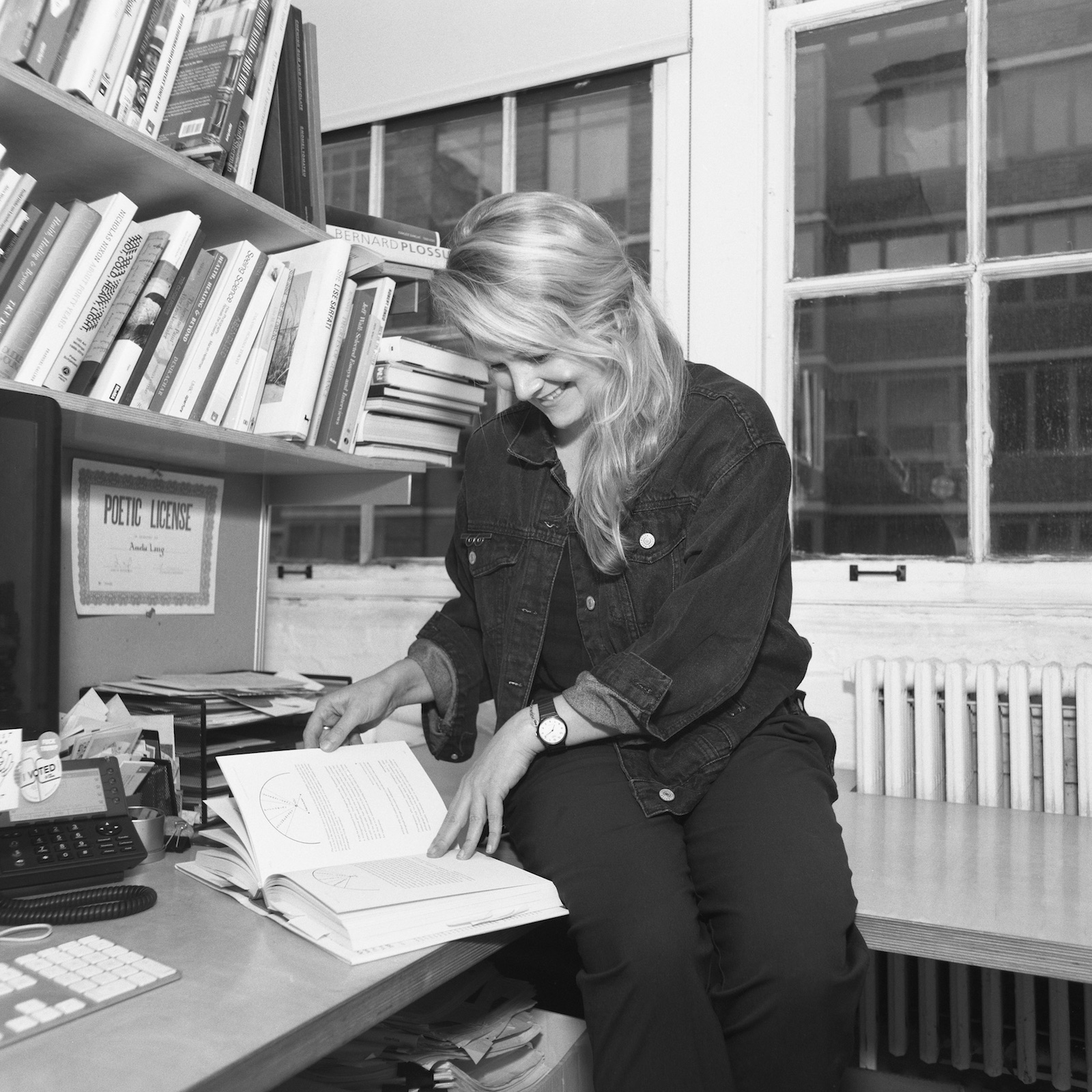

Jacqueline Bates and Amelia Lang

Jacqueline Bates is the Photography Director of The California Sunday Magazine and Pop-Up Magazine. California Sunday won the National Magazine Award for Photography in 2016 and 2017, the first title in 25 years to win in consecutive years. The Society of Publication Designers named California Sunday Magazine of the Year in 2018 and 2019. Previously, she was the senior photo editor of W Magazine and worked in the photo departments of ELLE, Interview and Wired. Bates holds an MFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts and her work has been exhibited internationally.

Amelia Lang is Associate Publisher at Aperture Foundation in New York. She has worked on dozens of publications as both project manager and editor since joining the organization in 2011. She previously lived in San Francisco, where she worked as a curatorial assistant, archivist and project manager on photography exhibitions and publications. She received her BA in Art History and US History from Lewis and Clark College and in 2016 completed The International Leadership Program in Visual Arts Management, a joint program accredited by New York University, the Guggenheim, Bilbao, and University of Deusto, Spain.

Photographs by Gillian Laub & Taylor Kay Johnson

Jackie Bates (l) & Amelia Lang (r), photographed by Gillian Laub

Amelia Lang: Jackie, it’s wonderful to talk to you. You have a fantastic, full-time job as the Director of Photography at The California Sunday Magazine. That sounds stable and responsible! But let’s start by going back in time—what has been the most precarious financial chapter of your professional life?

Jackie Bates: The years I was living in New York while studying at the School of Visual Arts and just starting out in magazines were the most difficult but also the most rewarding. For a few years during ungrad, when I was studying photography, I had three jobs—one was unpaid. I worked for two years at the Whitney Museum in the photo department. Another job was retouching nipples for a men’s magazine before the images went online. I babysat for the senior fashion editor at GQ every Saturday night and I did art returns for an art magazine. I always knew I wanted to work in the photography world somehow, but never as a freelance photographer. My photography was so personal—about my Italian-American family in Westchester, NY—I never thought that could translate to the editorial or commercial world. I had so many student loans and I was scared to default on them. I knew I had to get a full-time job somewhere. I looked at my friends who didn’t have those loans and they were able to take so many more chances than I ever could. I was so envious and so broke. Two weeks out of school, I got a job at Interview Magazine as their photo assistant, making less than 30K a year. It was stable. I was able to make my loan payments. I ate half a bagel for breakfast, the other half for lunch and we would always work late, even when not shipping, so I ate dinner at work a lot. Without that little perk, I wouldn’t have been able to pay rent and student loans.

AL: It’s great that you always knew you wanted to work in photo—it’s a rare gift to have that clarity. And I am sure being motivated by that goal made those half bagels worth it! And interesting, too, that you understood your photography practice was personal and that you wanted to keep it that way. That understanding takes a long time for some people.

JB: Yes, it was always clear. Tell me about your first years working in photo. How did you make it work?

AL: Similarly, I had several part-time jobs after I graduated from college. I moved back to San Francisco in 2007 from Portland, Oregon, where I studied Art and US History. There weren’t a lot of job opportunities in 2007-2008 (it wasn’t the best time to graduate college) and I ended up juggling several part-time projects. In doing so, however, I got to see a lot of different sides to the art world. I worked for an artist-in-residency program, managed a photographer’s studio, assisted an independent curator with a private photography collection, created a photo archive, helped to curate exhibitions, worked on arts and education initiatives, etc. It all swirled around photography—I think in part because there’s such a strong history of photography and photography community in Northern California. Three of those part-time jobs were in Marin County, which was ironic as I had worked so hard to leave and move to what I then considered to be “the city.” I found myself spending all my money on gas, driving back over the Golden Gate Bridge, against traffic and toward my hometown. I am really proud of the work I did there, but I felt like I was swimming upstream, like salmon do, but also treading water.

JB: You and I did a geographical swap. You’re from Northern California, living in New York; I’m from New York, living in San Francisco. When you were growing up out here, did you always know you’d work in the arts? Tell me about the decision to move to New York, did you think you’d be out there as long as you have?

AL: My family – dad, mom, stepmom, brother – have all worked in the arts in the Bay Area for decades. I always felt like it was a special community that I wanted to participate in and contribute to. But eventually, it became too hard to juggle all those jobs. I also really love school, so I applied for both an internship at Aperture Foundation and a Master’s Degree in American Studies at Columbia University. I heard back that I was accepted at both places on the same day and I felt like it was a strong sign to make a big change. I had no money and I was twenty-five. But I had these two institutions, one academic and one cultural, welcoming me and I was really excited by the idea of an intense level of thinking and working. I flew across the country and into a huge snowstorm, with my precious sourdough starter tucked into my purse. Very cliché, I know… I don’t know how long I thought I would live in New York but I sold my car which, for a Californian, is a strong symbolic gesture of letting go.

Jackie Bates, photographed by Taylor Kay Johnson

“Stressful work environments always stem from the top down and I feel incredibly lucky to finally work at a company that is run by a team who trusts their art department.”

AL: What did you do, work-wise, when you first landed in San Francisco?

JB: I moved out West to take a break from magazines but that lasted about six months. I thought I wanted to try working for a big tech company to tell stories for a global audience. And perhaps help pay off some student loans before I retire. My best friend, Carrie Levy and I art directed the rebrand campaign for Airbnb, which was a very memorable experience. To see images, shot by Emma Hardy, on billboards and buses that we had helped create and that felt a bit more artful than what you would normally expect from a tech company. We traveled around the world for six weeks, and Carrie and I still love each other to this day, ha! But as I was accepting that freelance gig out here, I met Doug McGray who was starting a new magazine. He had just asked Leo Jung to join as Creative Director, as the first employee. He and I met, and we chatted for a while about what the magazine might be—and he asked me to describe my photography sensibility in one word. I said: cinematic. He told me at the end of the meeting it was the same word he was using to describe what this magazine might be. I knew that I would only return to working in publishing if it was to work with kind people. Stressful work environments always stem from the top down and I feel incredibly lucky to finally work at a company that is run by a team who trusts their art department. It shouldn’t be rare in this industry, but it is.

AL: I never knew all this! It means a lot when you are on the same page as your team—before you are a team! Staying with this idea of geography and as someone from the Bay Area, living in New York (two extremely expensive places to live), I often wonder if it’s essential to live in such expensive places in order to contribute to the photography world and conversation, be that as a photographer, editor, freelancer. What do you think?

JB: I think going to school in New York was amazing because of the access to museums and professors (Tina Barney was my thesis advisor!), but since moving out West, I’ve come across so many groups of people making work outside of cities. My friend Annick Sjobakken left New York to move to Iowa so she could make work, have a studio space bigger than a shoebox and raise kids. She comes to New York to see shows a few times a year and because of her online community, she is still able to be part of the conversation. It doesn’t matter as much anymore where you live. I sometimes have FOMO when I see the openings you’re at, but I know that I can see most of the show online or on your Instagram Stories, when you decide to actually post.

AL: I should start a special FOMO handle for you that’s all and only New York openings. But those of us that live here are very often too exhausted to go anywhere! That’s reassuring to hear about your friend Annick. I hope there are more and more ways for creative people to live in affordable places and have time to make new work without so much financial pressure.

Amelia Lang, photographed by Taylor Kay Johnson

“To work at an organization that has been around for so long and at a place that supports both an older legacy and also looks toward the future is very special.”

JB: What was your first day like at Aperture, back in 2011, versus today, in 2019?

AL: I started at Aperture as an intern in the book program and it was a smaller department then. I worked for Lesley Martin and she taught me a tremendous amount about the process of making books, sequencing, working with artists, and working on deadline. On my first day, I checked the last text corrections in Rinko Kawauchi’s book Illuminance. It was a really exciting time and there were some great projects coming through. But it was also probably one of the most stressful times, financially, in my life. I was a full-time intern, going to Columbia at night and babysitting for a family on the Upper East Side. But I was energized and really happy to be in New York. I left graduate school after the first semester; it was too expensive and Aperture offered me a job as an Editorial Assistant. Lesley started The Photobook Review around then and I was really interested in the conversation around self-publishing, traditional publishing, gallery publishing, etc. And distribution, Amazon, Instagram, book fairs, and marketing tools—lots of things were and have continued to change since I started in 2011. It was an amazingly steep but stimulating learning curve in the early days. And to work at an organization that has been around for so long (since 1952!) and at a place that supports both an older legacy and also looks toward the future is very special. Speaking of which, what is it like to start something brand new?

JB: In New York, I had always worked for established magazines that had been around for decades (Interview, ELLE, W). Starting something from scratch was such a unique opportunity. On one hand, I was so thrilled to define the look and feel of a magazine that didn’t yet exist. And on the other hand, I was extremely scared. I struggled with self-doubt. But, I also trusted myself enough to go with my gut. But it is hard to shake the feeling, still, to this day—five years after we started the magazine—that I don’t know what I’m doing. I started simple, though and knew that I wanted each picture to have a strong sense of place and it was important for me to feature emerging and established artists in each issue—I had come from magazines where we mostly worked with photographers who were quite well-known and shooting for multiple commercial magazines every month. Part of what I loved about magazines was discovering new photographers. Each week while getting my undergraduate degree at SVA, I’d go to the library and write down artists names that I would learn by flipping through magazines like W—Dennis Freedman’s era of W—in addition to everyone’s names who worked in the photo department (I remember meeting Susan White a few years ago, who was the longtime Photo Director at Vanity Fair and I told her about how I used to look at her name on the masthead and dream of meeting her one day). I wanted that same sense of discovery when looking through California Sunday. There are so many talented people out there; I want to slowly give as many of them a chance as I can.

“The more work I look at, the louder that gut is about what I like and what I think is less interesting.”

AL: I feel lucky that I have a group of people that I consult when I need a little extra confidence and well, you’re one of them. Did you have a few people or group that you trust as a sounding board in those early days? A panel of trusted voices, other than your own?

JB: Yes, I would say my number one confidant in my professional and personal life when we started the magazine in 2014 was Carrie Levy—a fellow New Yorker—but I didn’t know her when we were both there. Gillian Laub, who photographed you and I last month, introduced us. She said she knew we’d be best friends and she was right. Carrie gave me invaluable advice when we were starting the magazine and listened to me in all my moments of wondering if I should quit magazines and work at See’s Candies. Also, before I hired Paloma Shutes to be my Photo Editor, she was a really wonderful source of knowledge for West Coast talent. She’s been at the magazine now for over two years, and I am so grateful for her skill and expertise. Who do you call (besides me, ha!) and in what moments of your work life do you find you need extra support?

AL: I have a few people who work in the photo world that I rely on a lot, but I also have a group of friends that work in other creative fields or completely different industries all together. It’s nice to get some advice outside this community at times. Something I have always liked about what you put in the magazine is this mix of established photographers with younger artists that I perhaps have not heard of. It always takes a strong gut to see work that other people haven’t yet liked and trust that it contributes to the community in new and exciting ways. I find it’s a bit like a muscle. The more work I look at, the louder that gut is about what I like and what I think is less interesting. How do you find new work?

JB: Thanks. It’s something that is so important to me. One of the highlights of my time at the magazine has been meeting with students in friends’ classes at CCA here in SF and in Long Island City at Laguardia Community College. I find work through teacher friends, lots of recommendations from photographers—I find that these days the industry has become less competitive, and it’s more supportive overall—or maybe I’m delusional; I don’t know. I was working with Daniel Shea on a photo essay in our first issue; he started recommending friends to me, and I was so taken aback by that. It was so refreshing. I also go to portfolio reviews (New York Times Lens Blog is my favorite), book fairs, openings and there’s a new app called Instagram, which I really adore.

AL: I use an app called Instagram too. And like you, I do portfolio reviews, go to openings, MFA shows, etc. I also really believe in publishing artists who didn’t get enough recognition or books published at the time they were making work. I edited two books by artists who were really active in the 1970s/1980s, Robert Cumming and Jo Ann Callis, who both deserve more attention. Those books both came through Michael Famighetti, the editor of Aperture magazine, who published portfolios of both Cumming and Callis and the editorial team here all agreeing there was a lot more than a portfolio worth of important work that needed to be shared.

JB: Jo Ann Callis is remarkable. What was it like working with her?

AL: She’s an amazing artist and making the book was a really fun process of finding an author and designer. I like thinking through the elements that help to shape and support a body of work. Also, Jo Ann and I had a very sweet personal connection and I still see her when I go to LA. And she’s always, without question, the best-dressed person in the room.

“Having an impact on someone’s career at the beginning brings me so much joy.”

JB: Besides working directly with artists, what’s the most inspiring part of your job? Where do you find inspiration and what do you look forward to most coming to work?

AL: I have shifted my role a bit, away from editing books at Aperture, to an interest in how non-profits and arts organizations operate. This includes working on fundraising, project management, sales initiatives, budgeting, how teams work—really boring things to talk about at an opening! I did a course in Arts Management at the Guggenheim in Bilbao a few years ago, with managers in the arts from all over the world, and it really inspired me to redirect and look at systems and structures that support publishing and cultural organizations.

JB: It’s not boring. It’s quite rare that you are able to touch on so many different parts of the business. I don’t think many people have that experience in their jobs. Usually a job’s focus is rather narrow. So many people think working in magazines is extremely glamorous—I’d especially get questions asking if The Devil Wears Prada was accurate when working at fashion magazines—but I like to joke that I’m basically an accountant.

AL: It’s true. I do get to wear many hats, as they say. And what about you? What are the really exciting parts of your job, beyond accounting (which is very important!).

JB: I love my calculator. My coworkers always notice when I’m using it because they, without fail, make fun of me. You touched upon it earlier, but I love working with young photographers—like Taylor Kay Johnson, who shot our portraits. I met her when I was speaking to my friend Jess’s class at CCA here in SF. We kept in touch. I put her graduating photo class on an Instagram takeover in 2016, and then I commissioned her to be one of 19 photographers to shoot our anchoring photo essay on where people feel most at home, alongside photographers like Gregory Halpern, Katy Grannan and Mark Steinmetz. And then we exhibited an expanded version of that photo essay in New York at Aperture in December, so she had her first gallery show in Chelsea, which she said “blew my mind and made me believe that my work had the ability to move people – just like these photographers’ work had moved me while studying their work in school.” There’s nothing better than that. Having an impact on someone’s career at the beginning—just taking that extra moment to get on the phone and walk through a story, pass references back and forth, answer any and all questions about budgets, contracts, expectations, what to send/what not to send to an editor—brings me so much joy. I love how collaborative my job is. My team (Leo Jung, Paloma Shutes, Annie Jen, Supriya Kalidas, and Tom Bollier) is supportive, smart, funny, and kind. There are no egos. People have been so positive in their response to the magazine and its photography but it really has nothing to do with me. It’s all about our contributors who work tirelessly for us and the incredible subjects who open up their lives to us in each issue. I am a shy person by nature (some people who know me well may roll their eyes at that statement), but so much about being a photo editor is talking to people. Getting on the phone. Going to openings with my incredible art department. Listening. Watching. I spoke recently at a launch event we were doing and went through the entire issue and how I didn’t meet any of the photographers I had commissioned on my own. I met them all through other people. Other recommendations from photographers, friends in the industry, at an open house in Bolinas… I used to be afraid to ask for help because it would make me look like I didn’t know anything about photography. But that’s not true. The industry is moving so damn fast, none of us know what we’re doing. So why not ask for some help once in a while? If you normalize that and create a supportive community among your peers, everyone benefits. One of my favorite things to do each spring is visit Laguardia Community College, where my friend Maureen Drennan teaches. I love hearing them talk about what is exciting to them about photography now. It’s important for me, too, for them to walk away from our time together armed with advice on getting into the editorial world. I make sure they know what questions to ask before agreeing to an assignment. So many times you just say yes to get published. You take a low rate. But taking a low rate hurts not only you but also the industry. Sometimes people ask me to recommend photographers “who will be OK with a low rate” and I almost always say no—get a better rate for them and then come back to me, and I’ll give you some names. It works, I think.

AL: I believe in our network of eyes, so to speak. I love getting emails from my friends who are photo editors asking, “Hey, do you know of a photographer living in Dublin?” Why would we not support and share what we have seen and appreciated? That matchmaking is so satisfying, and I like to think that the photo community is moving toward a supportive and less competitive culture.

“I want our culture to value a new generation of artists and a new generation of people that support artists.”

AL: Do you think about the future of media more than when you lived in New York, given you are living and working alongside the tech industry (at least geographically)? What’s exciting about where we are heading and what’s troubling?

JB: Since moving to San Francisco, I’ve definitely thought more about the intersection of media and tech. Naturally, California Sunday has covered the tech industry heavily and in a variety of ways—we’ve interviewed tech workers pushing for a more ethical Silicon Valley, we’ve published interviews about the lack of diversity in tech, and much more. I’m proud of the stories we’ve told about the industry. With regards to the media landscape specifically, our company, Pop-Up Magazine Productions, was acquired by Laurene Powell Jobs’ Emerson Collective in November 2018. That was a really exciting, positive moment for us—to work with an organization that shares our belief that great journalism and storytelling can inspire people. What troubles you about the future of publishing?

AL: Publishing has and is and will continue to change dramatically. The art book fairs, now in most major cities around the world, always make me reflect a lot about photobook making specifically. When I attend or work the booths, I always ride an emotional roller coaster that includes, “Wow this is so inspiring. Look at all these people who have actualized their creative ideas. What a nice community!” and, moments later, “Why do all these people think they need books? Look at all this paper and shipping, there’s too much” and back around to, “I am so inspired, humans are incredible!” But you asked me about the future and what really troubles me is the increasing lack of government support for structures like the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and public arts education. This is a much more macro worry than art book publishing and photo editing and maybe it’s because my mom was an art teacher, but I really see that arts education and national support of creative thinking and learning is essential and being threatened. I want our culture to value a new generation of artists and a new generation of people that support artists. And I see the cost of living and funding cuts making it really hard to work in the arts and be an artist. That’s what troubles me deeply. But we can’t end with troubles! I know that you’ve started working with organizations like Los Fotos and Project Rebound through California Sunday. Tell me about that.

JB: Whenever we are about to start a new issue, Leo and I try to look at it as a whole and how we can tell each story in the most surprising, visually dynamic way. Also, what story lends itself to an experiment—perhaps working with an unexpected artist. When we were working on the Teens issue in 2017, we did a ton of research into youth organizations across California. Paloma (Schutes, photo editor at California Sunday) found Las Fotos Project, whose mission is to elevate the voices of teenage girls from communities of color through photography between the ages of 13 and 18 from low-to middle-income households. She worked closely with a student there, 18-year-old Textli Gallegos and had her shoot a young teen boxer in Fresno. It was her first editorial assignment. She did an amazing job. Several months ago, photographer Brian Frank was teaching a photojournalism class at SFSU in partnership with Project Rebound, which is an organization that helps men and women returning from prison. He called me in the middle of class one day and said I had to meet some of his students—that they were incredible. Fast forward to our April 2019 issue, we were tasked with commissioning Elizabeth Weil’s story about a mobile classroom, via bus, that’s parking in some of San Francisco’s poorest neighborhoods to offer adults a third, fourth, and fifth chance to get a GED. Weil examines the lives of these adults—who have been failed educationally and many of whom were formerly incarcerated—in a city where it’s incredibly hard to be poor, and what this opportunity means. Brian’s students, Chris Shurn and Eugene Riley, were a perfect fit for the story. Brian mentored them through the process, since it was their first editorial assignment—which I was grateful for. We also featured an interview with Chris and Eugene with my editor Doug McGray, which is one of my favorites.

AL: These initiatives are really encouraging. And a good reminder that no matter what seat you are sitting in, be that as a photo editor, publisher, photographer, we can all make choices that reflect the direction we hope our culture will head in. I’m inspired by you, Jackie Bates! Let’s end our chat on this: what has been your favorite issue or commission so far?

JB: That’s a hard one because I love all of our stories equally. Just kidding. I’d say our first cover shoot by Holly Andres was memorable—Leo and I flew to Portland—making the first cover was full of experiments and questions and playing and making mistakes, and Holly was so game and delightful. I love a photo essay we did for our first themed issue (we do one a year), which was all about sounds of the West, and I commissioned Elle Perez to shoot music scenes in rural parts of California and Michael Schmelling to shoot the urban music scenes. Our next themed issue was about Teenagers—and Alessandra Sanguinetti photographed teens across California hanging out. Lastly, in December, we published our first photography issue, on the theme of Home. There were 34 photographers in the issue (our normal issues have around five). The issue was organized into three sections: stories about people far from home, in between home, and close to home. The anchoring photo essay had the work of 19 photographers in it, and, as you know very well, we expanded that photo essay into a gallery show, which was at Aperture Gallery. I owe so much of that to you and your support of what we’re doing at the magazine. Tell me about yours!

AL: That show was all you guys! It was so fun to have so many Californians in the office while the gallery was getting installed. I loved working on Aperture Magazine Anthology—the Minor White Years: 1952-1976, edited by Peter C. Bunnell and Lesley Martin. I know you have a copy of this! It was published on Aperture’s 60th anniversary, in 2012, and covers the first 25 years of the magazine. To circle back to what we talked about earlier—how magazines start—I love how this book charts those early conversations and the editorial decisions that went into shaping the first issue and the direction of the publication. There are selected articles and images that appeared in the original issues reproduced in the book and a really wonderful timeline that includes images of each cover, and the early covers are so beautifully designed. A lot of the founders had West Coast roots (Aperture was founded in San Francisco) and many of the early issues include images of the West, which you know I love. Peter Bunnell, who began working for Minor White in 1955, would call me every morning during the proofing stages of the book. Aside from the corrections or adjustments to the sequencing and images changes, etc., those phone calls also included anecdotes about working with the photographers and writers of that time period, a morning photo history class, of sorts.

JB: I love that book. And I love you. Text me later.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.