Joanna Cresswell

Joanna L. Cresswell is an arts writer and editor specialising in photography and culture and based in London. She has written for a number of publications, websites and organisations including AnOther, Aperture, American Suburb X, Dazed, The British Journal of Photography, Paper Journal, Photomonitor, The Photographers’ Gallery and more. She has contributed essays to a number of books and journals, most recently New Scandinavian Photography (Blackdog, 2015), and edited publications including Self Publish, Be Happy: A DIY Photobook Manual and Manifesto (Aperture, 2015). Previously Managing Editor at Self Publish, Be Happy, Joanna is currently Editor at Unseen Amsterdam’s Unseen Magazine.

Anne Carson – Autobiography of Red

Of all the books I own none are more precious, or have had a more profound effect on me than Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red. The book is sold as “a moving portrait of an artist coming to terms with the fantastic accident of who he is” – isn’t that just lovely? The story is a sort of re–worked ancient Greek myth for the present day, and as with all of Carson’s works, it teeters in the space between novel and poem. The protagonist – a young boy who is also a winged red mythical creature – seeks solace behind the lens of a camera. It’s haunting and elegiac and the language is so visual and rich and beautiful it makes my heart hurt. I’m still waiting for something to move me as much as it did the first time. I also have this inexplicable draw to volcanoes because of Carson – I’d like to put together a book of words and pictures about them one day.

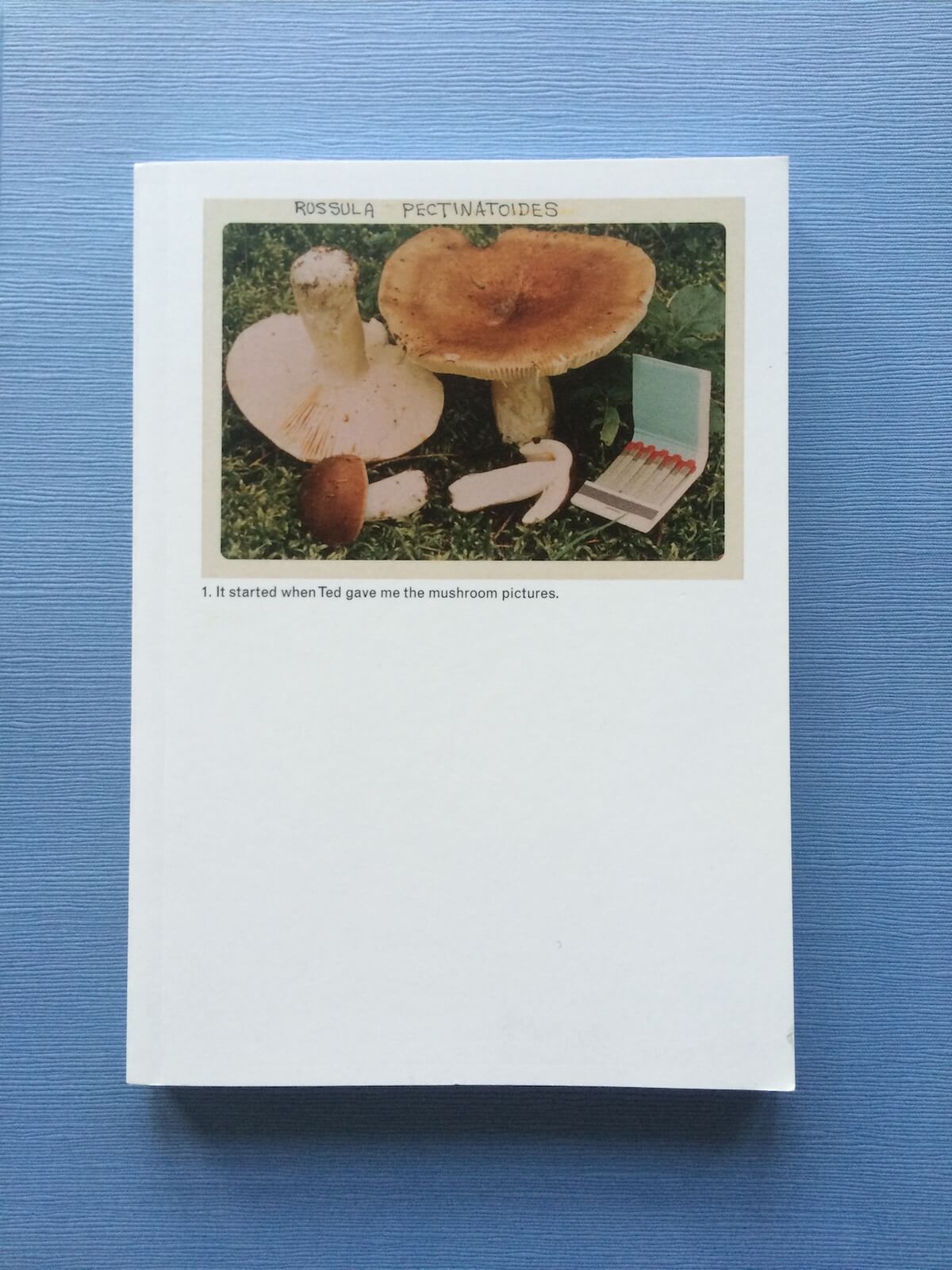

Jason Fulford – The Mushroom Collector

When I think of my all-time favourite photobooks (which is almost impossible and, for the most part, always changing) there’s one particular book that never goes away – Jason Fulford’s The Mushroom Collector. I don’t feel like I could talk or think about photobooks without acknowledging what Fulford does with the form – the way he connects images, conjuring small conversations based on form and metaphor that ebb and flow throughout the pages, is just so pleasing. Photography is all about searching out those associations, however small or subtle, and using them to weave the fabric of a narrative, isn’t it? I’m also endlessly taken with the way that an idea grows and spreads in Fulford’s practice – a memory or an object triggers the idea for a project, a project manifests as a book, and then the contents of the book shape-shifts back out into an immersive experience for the viewer. On a related note, there’s a conversation that meanders through thoughts and images between Jason Fulford and Aaron Schuman that I continue to return to here.

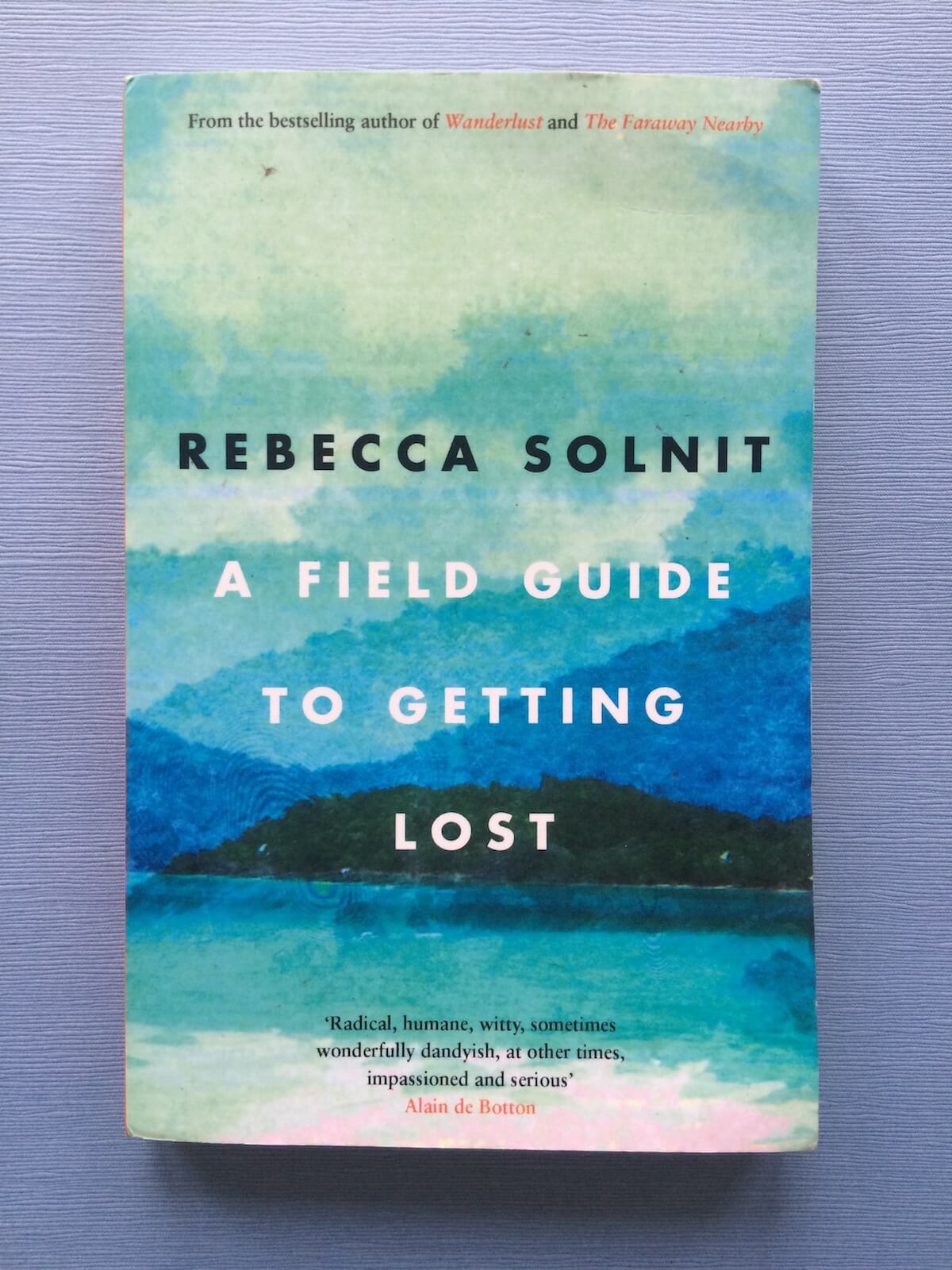

Rebecca Solnit – A Field Guide to Getting Lost

My partner’s father – Dennis, an incredibly well read man who likes to walk a lot – got me this book. If I could have a dinner party and invite anybody in the world that I wanted to, Rebecca Solnit would be at the very top of that list. I love almost everything she has to say. I’ve chosen to mention A Field Guide to Getting Lost because it’s personal and poignant and moves through all sorts of ideas – philosophy and photography, memory and the act of walking are just some of them. I love this kind of book. I like things to be discursive and I like to see what happens when photography is put into conversation with all sorts of other mediums and areas of interest.

I also have to mention Men Explain Things to Me, and I cannot recommend the Men Explain Lolita To Me enough either – you can find it online and it’s humorous and infuriating in equal measure. I write about – and for – women artists a lot and I could only hope to be as witty and as brilliant as she is in doing those people justice.

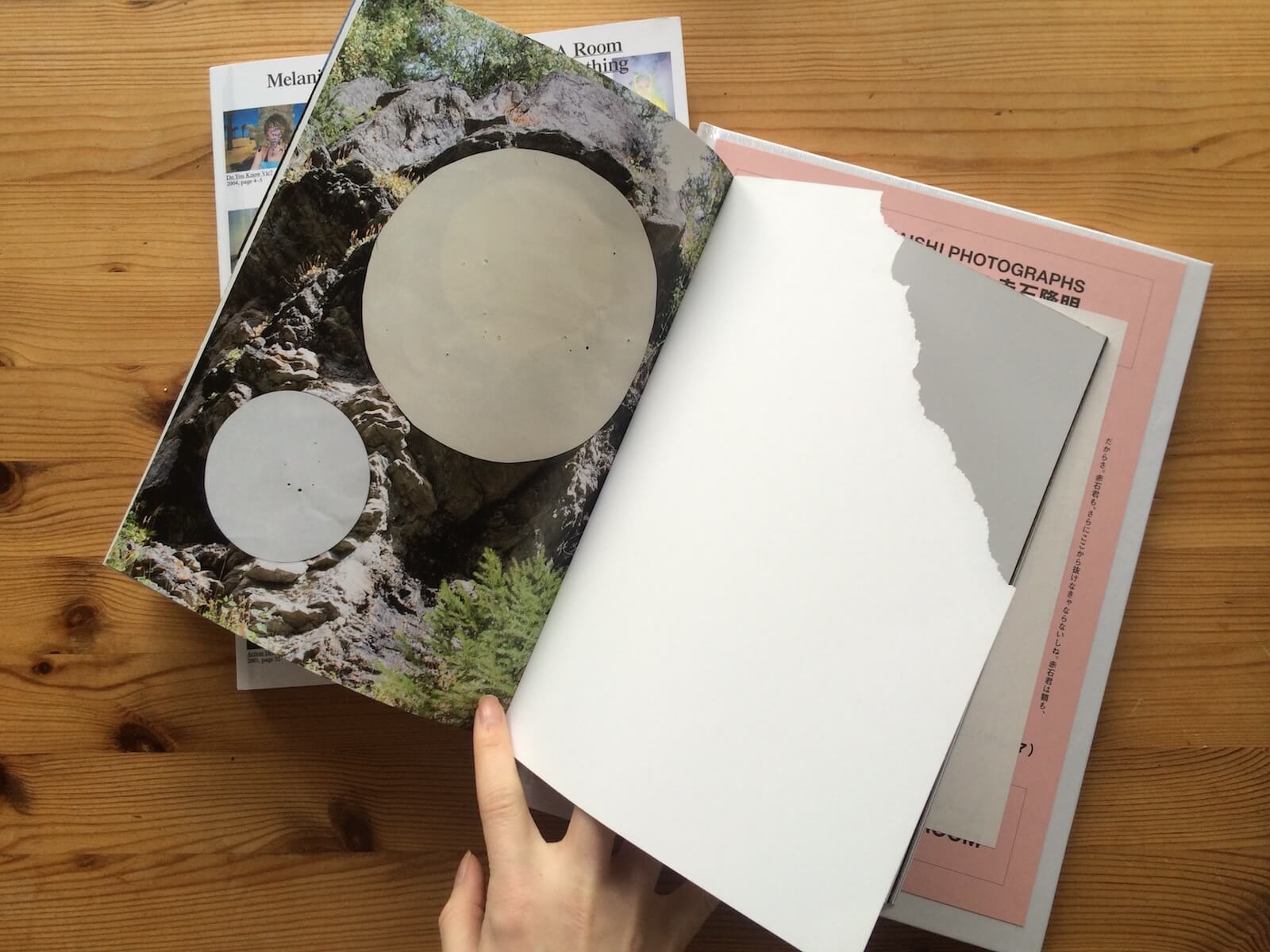

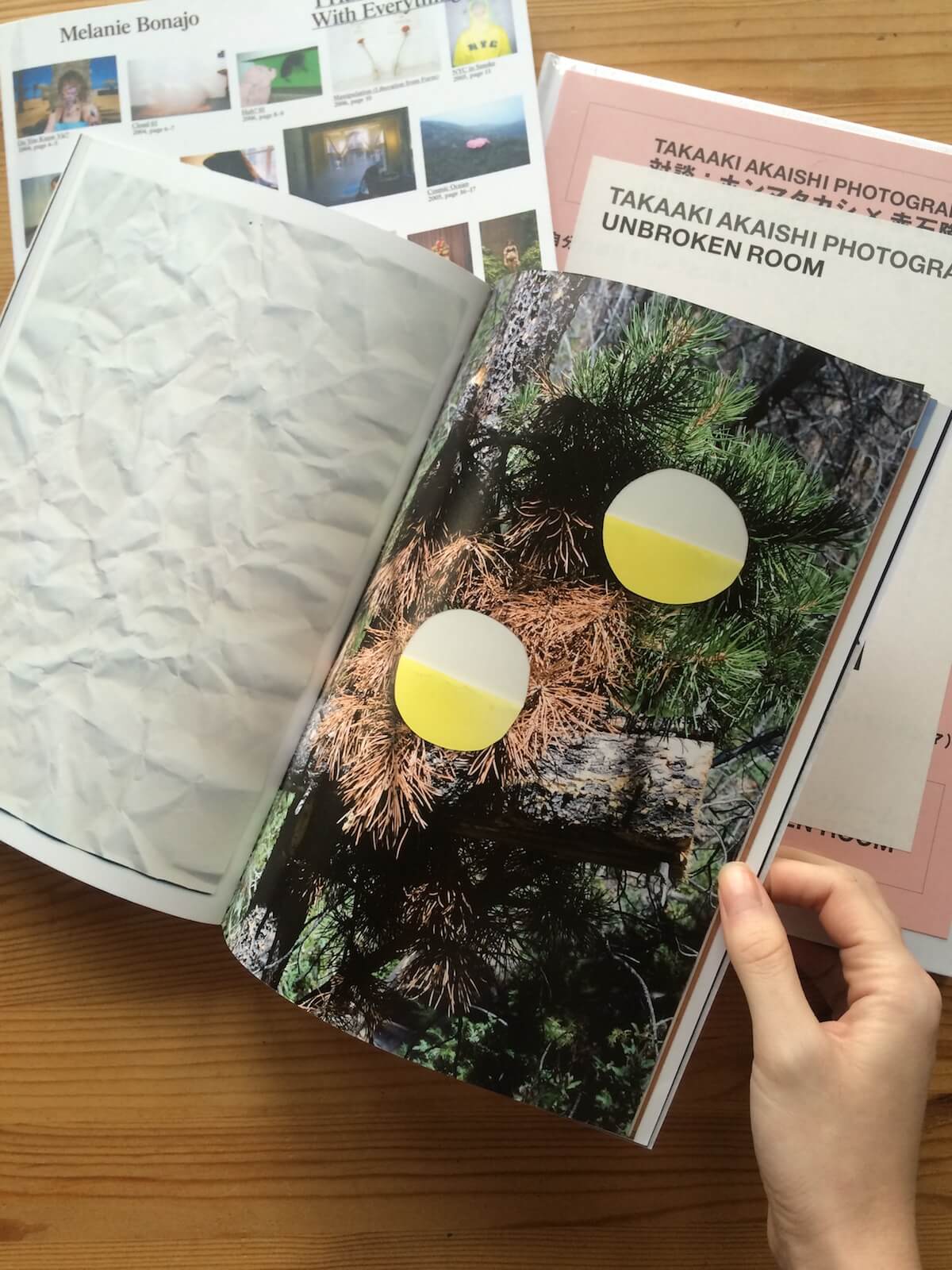

Letha Wilson – Between A Rock

Letha is absolutely one of my favourite artists. Her idea of photography is stretched and warped, and falls far beyond the confines of the frame. I love the near-idyllic landscape-porn of Utah and California that her pictures offer us. Between a Rock is a thin, pamphlet-style sort of publication that she made with Gottlund Verlag in 2014. I had wanted a book – any book – by her for ages and finally I got my hands on the last copy of this and it didn’t disappoint. I love it because she continues to work with the idea of intervention and disruption within the landscape but in book form. Images of landscapes are torn, hole-punched and scored into. It’s wonderful to run your fingers across the pages. I return to it because it reminds me that it’s important for a book to have an element of interaction – it’s not just pictures on a page but how the whole object speaks to you, and the experience you get from it, in the end.

If there were an ‘honourable mention’ here, I’d also say Luke Stettner’s Eyes That are Like Two Suns.

Michael Ondaatje – In The Skin of a Lion

In The Skin of a Lion is one of my favourite novels. There is a certain quote from it that has stayed with me since I read it the first time, and often I return to it when I’m writing about other people’s work. It goes:

“The first sentence of every novel should be: trust me, this will take time but there is order here. Very faint, very human. Meander if you want to get to town.”

If I had my way, that sentence would be the precursor for all stories – literary or visual. I have no real need for the traditional pace of a story with a beginning, middle and end as a reader or a viewer, because that’s not how life really works. I like it best when things unfold slowly, over time.

Yto Barrada – Retrospective

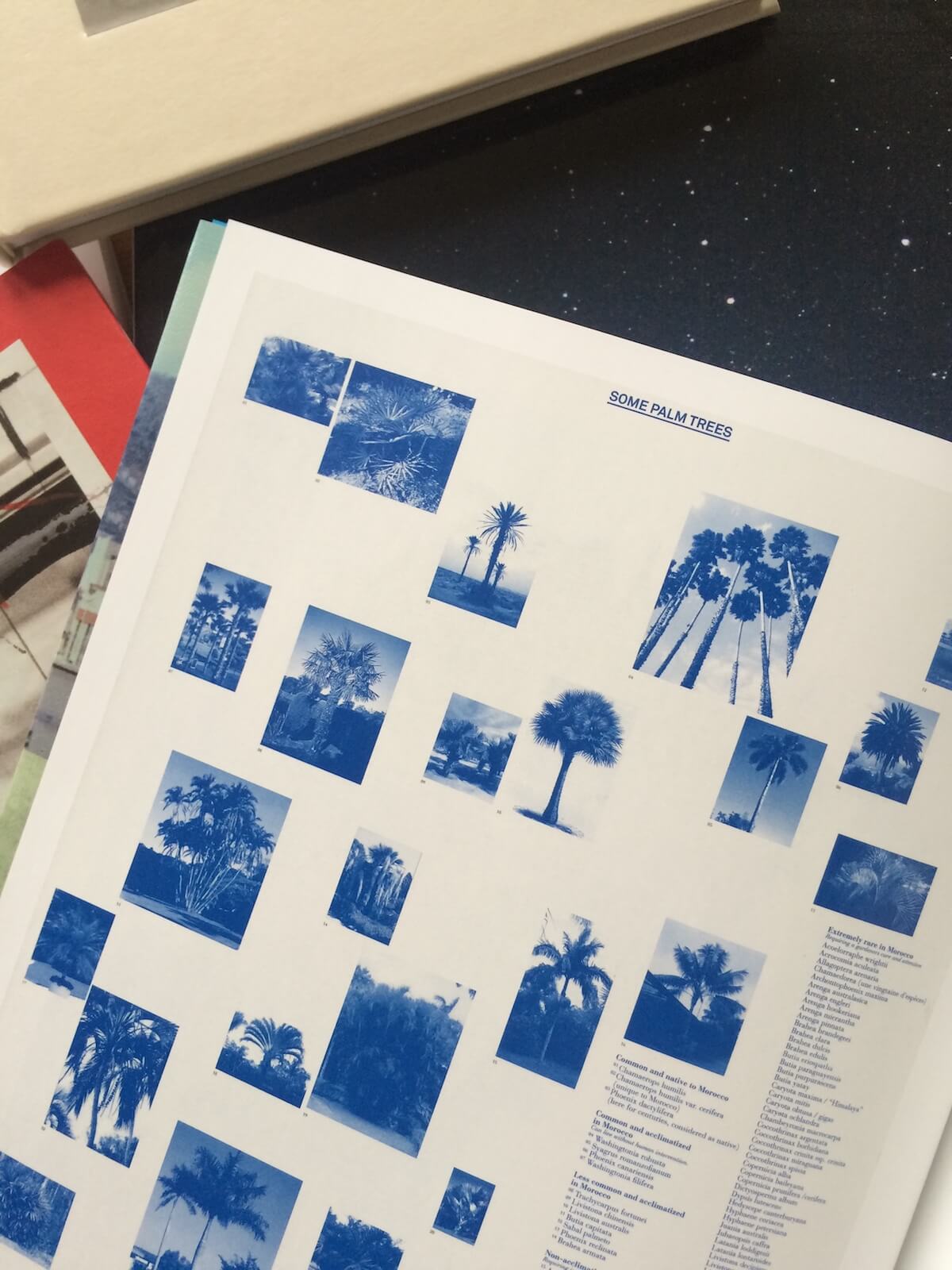

This book, and Barrada’s work in general, holds a particular resonance for my partner Oliver and I, because we set off on a trip to Tangier to visit Barrada’s Cinematheque de Tanger after only having known each other a few weeks. We watched three films, all in French and hardy understood a word but it was one of the best experiences. We got t-shirts and shortly after ruined them in the washing machine. The book – which traces a retrospective journey through Barrada’s work exploring postcolonial history with a focus on her hometown of Tangier – is beautifully printed with different papers and full up of images of Barrada’s films and sculptures and installation work. Both of us return to look at it from time to time. I particularly love her collections of blue-toned pictures of palm trees.

Ed Ruscha – A Few Palm Trees

Talking of palm trees, how could I work with photobooks and zines for so long and not acknowledge Ruscha? I’d buy his books if I could. Perhaps the thing I like best are his simple, straight-to-the-point titles that deny any sort of poeticism – they’re almost disarming. “Various Small Fires”, “Every Building on the Sunset Strip”. I run an irregular experiment in photography and literature over at Paper Journal, and I named it after my favourite of his books: A Few Palm Trees. I just love that title. It offered me the suggestion of a simple starting point with endless potential that I was looking for in a name.

Lucy Lippard – I See/You Mean

I picked up a copy of Lippard’s I See/You Mean a few years ago when I went to the New York Art Book Fair for the first time. The cover was bright purple and had this intricate white pattern on it – like a relief map – which I couldn’t take my eyes away from. The back cover promised a journey through palmistry, maps, tarot, mirrors, sexual encounters and overheard dialogue – what wouldn’t be to love? Lippard talks through a series of photographs in it and a loose narrative unfolds bit by bit. It was originally written in 1979 and they say it’s a sort of cataloguing of the emergence of her feminist consciousness.

Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs – As Long As it Photographs

Maybe the most important thing I’ve learnt through my work and all of the people I’ve been lucky enough to have conversations with in this industry is that there is a real value to humour in photography. I’m thinking of fun and the idea of ‘play’, yes, but also of a more subtle, wry wit, which Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs are modern masters of, I think. I first fell in love with them when their oversize publication ‘As Long As It Photographs / It Must Be A Camera’ made its way into the Self Publish, Be Happy Library, where I was working as Editor at the time. All of these strange objects are turned into cameras – from piles of books to turtles. It’s amazing, and really, really funny.

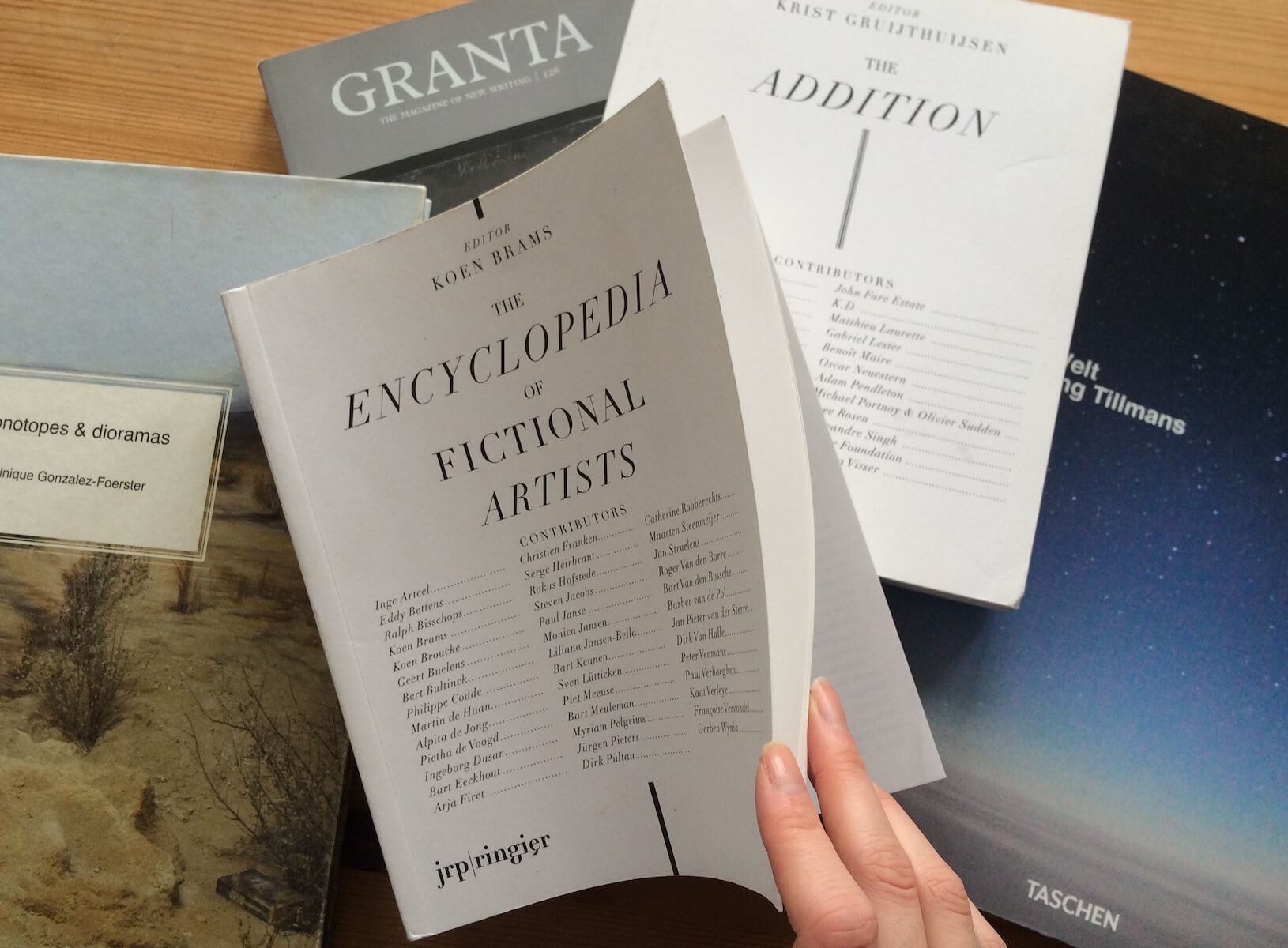

Koen Brams – The Encyclopaedia of Fictional Artists

The tussle between author and character is something that’s been of interest to me for years. I like books like Anna Banti’s Artemesia where the lines blur, and I like it when an author slips into their novel, and talks to their character. In this vein, I’ve thought about fictional artists for a long time and I picked up this book when I used to work in the bookshop at the Tate Modern on weekends when I first graduated. I dip in and out of it pretty consistently, and I’ve always loved reading about the fabricated artists that have appeared in literature through time. In a way, it traces a sort of alternative history of art. I always get the feeling that there’s further research in there for me somewhere, though it hasn’t revealed itself to me yet. Maybe it’ll be my life’s great work in the end.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.