Rose Marie Cromwell and Yael Malka

Rose Marie Cromwell is a photographic and video artist, based in Miami, whose work explores the effects of globalization on human interaction and social politics. Cromwell has been awarded a number of residencies and awards including a Fulbright Fellowship and a Light Work Residency. Her first solo show was at the Diablo Rosso Gallery and currently has a solo exhibition on view at Antítesis Gallery in Panama City. Her first book dummy was recently shortlisted for the Mack First Book Prize in 2017. Cromwell’s work has been published online and in print in a variety of international magazines, including the 2014, 2015, 2016 Vice Photography Issues, Camera Austria, Time Lightbox, ARC Magazine, Musee Magazine, The Oxford American, and The British Journal of Photography.

Yael Malka graduated in 2012 from Pratt Institute with a BFA in Photography and minor in Art History. She has participated in several group shows at various galleries such as Bruce High Quality, Philadelphia Photo Arts Centers, Sikkema Jenkins and Rubber Factory Posters, among others. In 2012 she co-founded the New York-based gallery, TGIF, and published two photo books with artist Cait Oppermann. She is from the Bronx and Israel and currently based in Brooklyn, NY. Her editorial clients include The FADER, New York Magazine, Bloomberg Businessweek, The Outline and Phile Magazine. She is currently working on her first solo photo book.

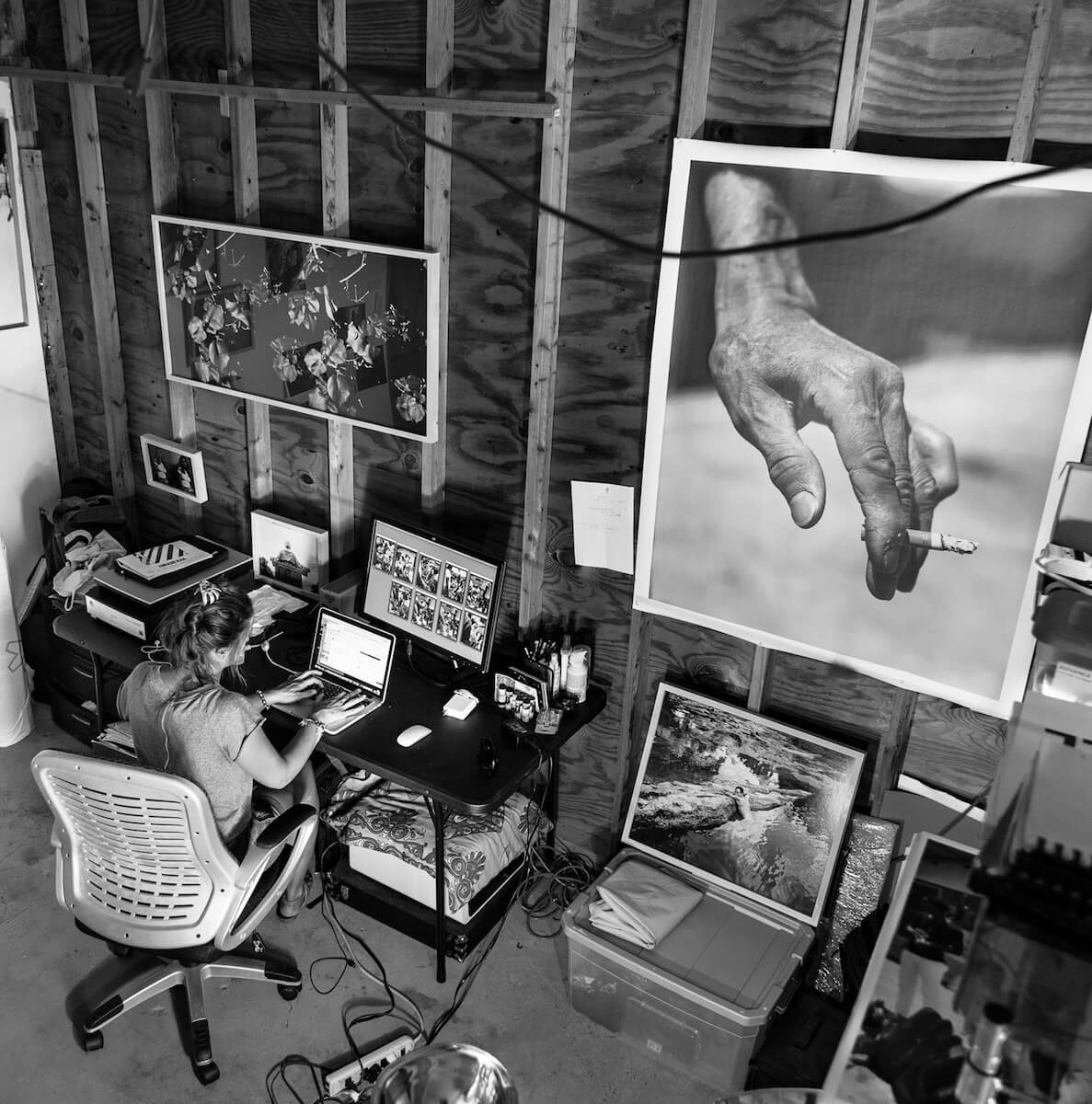

Yael Malka photographed by Cait Oppermann

Rose Marie Cromwell photographed by Anastasia Samoylova

“It was great being on the other side of the editorial world because now I know when I can ask for more money”

Yael Malka: I remember meeting you at the Vice photo show, which you had a few pieces in, last year after being a big fan of your work and just having hired you to do a photoshoot of babies for the FADER. I photo edited there for a good part of last year while Emily Keegin, the photo director, was on maternity leave. The babies shoot was actually one of my favorites that I got to commission. It was really playful and fun, but I know it was also super challenging because, well, babies, and also finding parents who were willing to let their children be photographed. I know it was a lot to put all that work on you but you handled it all so well. I was obsessed with all the photos – it was hard to choose! Shortly after The Vice photo show, you made another trip out to New York and you came to the office to show me new work and the dummy for your book. I really appreciated that you brought physical copies of magazines you had been commissioned to shoot for – and we just went through the pile. It was so old school and refreshing and I loved it. We talked for a long time about making work, commissions, traveling. We were sitting in that kitchen for like an hour! I had a few meetings while I was at The FADER where I was really able to connect with the photographer. This was definitely one of those times – we really got into discussing our process, our ideas, thoughts on photography and that was really fun and exciting. I don’t know if you remember it the same way, ha! I loved seeing the dummy for your book – it was beautiful. Where are you with the book now? I remember last time we talked you were looking for a publisher.

Rose Marie Cromwell: It is always so nice to meet people you work with, and photographers can spend so much time emailing back and forth with photo editors, that I really value the face to face time that I get with editors. I value making a relationship beyond the typical “here’s an assignment!” and “here are your images!”, so I too enjoyed our time in the FADER’s lunch room, and felt lucky that you took the time to look so carefully at my stack of magazines and book. I had been on your site and was really interested in your photo abstractions, they were original and done with care. I had done a couple smaller shoots for Geordie Wood, but I think the babies shoot was the largest I had been asked to do for the FADER at that time. I do like a challenge and the challenges were not only baby logistics, of which there are many, but also it is hard to make interesting photos of babies that do not just revert to “cute” or “upset”. You encouraged experimentation and that was empowering. It was also nice that you were hands on and present, and gave me feedback throughout the process. Speaking of babies, the book has also been incubating for a long time, and it’s ready to be birthed. It has gone through one more iteration since you last saw it, and I feel really good about where it is at, its done. I am excited to put it out in the world, because some of the images in it have only been seen by people who have held a dummy. The project also does not translate well in image edits of 10 or 20 and it was always meant to be viewed in book form. I do not have a committed publisher yet, but maybe by the time of publication of this conversation that will have already changed, fingers crossed. Looking back, how was your experience at the FADER? We haven’t talked since you left and moved to LA… Do you see more photo editing in your future? What is it like to be on both sides, a working photographer with editing experience?

YM: Oh, I loved working at the FADER. I learned so much and worked with truly incredible people. I became really good at negotiating. I learned more about storytelling and how to edit my own pictures. It’s always so hard to edit yourself, but it became easier after that job. I was lucky enough to shoot a bunch of stories for them while I was at that job and it got me really excited about making my work accessible editorially. Prior to that job, I tried doing editorial work and quickly realized it wasn’t what I wanted but I think it just took a few years to understand that I should be getting hired for my style, not just because I can take a picture and know how to use lights. I wasn’t connected to the stories I was commissioned and now I feel like I’ve made a very obvious shift stylistically so I get jobs that make sense for me and my work – which is exactly how it should be. Since I was able to make the kind of work I wanted to that fit my aesthetic, I decided it was something I wanted to pursue again. It was incredible to be able to start building up an editorial portfolio while I was at the magazine because when I left I had so many new photos and combined with my personal work, it was a perfect time to transition to working freelance. For that reason, I don’t think I’ll be going back to photo editing because I want to do my own thing right now. It was great being on the other side of the editorial world because now I know when I can ask for more money, I know how far I can push something, I know I shouldn’t be afraid to ask for something or make requests. I was always terrified that if I wanted to ask for a bit more money or had a concept I thought fit the story better that the photo editor would just be like, “okay, never-mind, let’s move on to another photographer.” This is something I talk with my freelance friends with all the time. I’m sure everyone can relate to that feeling where you’re obsessing and freaking all day about an email you need to send about a job and being terrified of what the response will be. But most of the time, it’s totally normal and not a big deal at all! When I chose someone for a job, it was because I thought they would be a fantastic fit for it and I trusted them. There were times where I was asked to give them a little more money and I was happy to do that when I could, but I would never un-hire someone for asking for more, in any sense. Do you know that dread-filled feeling I’m talking about when you’re waiting to hear back from a photo editor after you ask them a question you were nervous about asking? Have you had any experiences that ended up badly?

RMC: That is so great that you are taking the leap to freelance. That is a scary but exciting time and it is great you have a community to reach out to about business, because that is essential. I had a friend, whom I consider a mentor, who was generous enough to tell me a bit more about some industry standards, and negotiating tactics, and what was and wasn’t acceptable. Without him, I would have been lost. I started freelancing when was 31, which was 3 years ago, and just recently have left side jobs, such as teaching or cultural guiding in Cuba. It has been a learning curve, but what I have learned is that you are running a business.

I believe that a business philosophy has helped me take the edge and anxiety off of emailing. One has to know the costs of running the business to know what to charge, and what is your non-negotiable day rate (or cost of image permissions). In theory you are the vendor, you should provide your price. One doesn’t go to the mechanic and tell the mechanic what one is going to pay for them to fix one’s car. I know a lot of publications have fixed rates, but one can choose whether their fixed rate fits their prices. There might be times when you take a pay cut, for a project that might have other benefits, but if you do not value your work on a consistent basis to be asked to be paid justly for it, then no one else will. There will always be someone willing to do it for less, but they will not deliver the same quality you will. As far as negotiating with an editor, I think it’s important to keep in mind it is just business and not to take things personally. I agree that most of the time, if editors cannot comply with your request, then they will tell you that, and you can choose whether the job is worth it or not. I consider the other things I could be doing with that time, such as business development, or working on personal work. There have been jobs that I really wanted to take, but I couldn’t afford to. The editors offering me these jobs may not have had much control over the budget. I am still on good terms with these editors, and I am sure we will work together at some point. As you asked, yes, I have lost jobs through the negotiating process. It can be hard when you are emailing and all of the sudden an editor falls off. One time I emailed back to ask if we were going forward and they told me they had moved forward with someone else, for stylistic reasons. I wonder though if that person was willing to work for less than I was, or they offered him more. I’ll never know. In the end, I knew I couldn’t afford to do the job for what they were offering me, and so it was fine. Sometimes I have negotiated, digital for film or I’ve taken a day or two off the job, so that everyone is happy and comfortable. Another part of negotiating that does give me goosebumps is contracts. I have seen some crazy kill fee policies, and reuse of image policies etc. It can take some time, but I feel it is so important to carefully read and negotiate your contracts. As an editor, did you have to negotiate contracts with photographers? How did you find this process for yourself as a photographer?

YM: I totally agree with you and I think if you lower your standards for rates, contracts, etc., it ends up lowering the standard for the profession as a whole and it becomes the norm. Contracts are super important to read and ask to be amended if necessary. I usually negotiate the exclusive rights if it’s ridiculously long and reuse of photos and I have almost never had a problem getting it amended. There are some publications whose contracts are worse than others and that could turn me off from working for them. Also, if it takes forever to get paid, then I won’t be working for that publication again. Although, to go off of what you said, there have definitely been times where I’ve been paid very little or not at all but it was something I was really excited about and knew I could make photos I liked. For instance, for a recent job, which is probably my favorite commission yet, I wasn’t paid because it’s a new publication but they took care of all equipment, travel, food, film/processing and expenses and it was a really fun and fulfilling job. There are times where you need to consider if it’s worth the trade off and in this case, it was. But being on the other end of contractual stuff was not always fun. I could 100% empathise and usually agreed with what the photographer wanted, but because I worked at a company and it was about whatever their best interests were at hand, I needed to accept that. I always advocated for the photographer whenever I could but there were times when it would seem like I was fighting against the company I was working for and that didn’t make me look good so there’s definitely a balance that at times was difficult for sure. I think sometimes I made it difficult for the person who did the contracts or when I would try to get a photographer more money – it was like, “whose side are you on, the photographers or ours?” It was really both so it was definitely a struggle at times. What are your top 2-3 things that you need to fit your standards in a contract? Like if they wouldn’t change the terms, you wouldn’t take the job because of it?

RMC: I remember one time when I was negotiating a contract and I was nervous. I really wanted the job, it was a multiple day job in a country I love, with a lot of creative freedom, and a budget that was sufficient. But there were multiple things in the contract that I had to change. If they didn’t change them, I did not know if I could ethically do the job. However, after an intense call with their lawyer, we were able to find some common ground. I was so relieved, and felt empowered. My non-negotiable are: 1. Kill fees where I will not be sufficiently compensated for my time. 2. The rights to edit and crop my photos at the will of the editors 3. Image permissions that extend too long, or the right to be able to grant image permissions to others. I think that’s pretty basic, right? What about yours? Am I missing something?

“I believe that people do not expect women to negotiate as a man would, but I also know that they get offered less from the get-go”

YM: Yes, that is super scary when you have to do that, but it’s very important to make sure you stick to your standards. You have to make a bunch of mistakes and get screwed over a few times so you know never to do those things in the future – unfortunately that’s a common way to learn when you start freelancing. But I feel at this point, I know exactly what I want and am not afraid to ask questions or request amendments to contracts or ask for more money. I think as a woman, you especially need to be unapologetic about those things.

RMC: I believe that people do not expect women to negotiate as a man would, but I also know that they get offered less from the get-go. As a woman, it is definitely more of an uphill battle, but I also know my friends of color face an uphill battle too perhaps even greater. I believe the more that we communicate about these challenges, the more we are equipped to handle them. When I was starting work editorially in NYC, my competition was mainly established white male photographers, who had years-long relationships with editors. I was teaching at ICP and Aperture, while trying to finish a personal project in Cuba. I had a tiny work studio in Bushwick, lived in a small studio in Crown Heights and struggled to pay bills.

YM: You live in Miami, now, right? Do you like it better than living in NY? Do you think you’ve been able to get more commissions living out there? And have you been flown out to South America more?

RMC: My husband and I were eyeing Miami, as he was never a huge NYC fan. Miami was an hour from Cuba, 3 hours from Panama (where I used to live and go often still) and 3 hours to NYC. It was also more affordable. I started to tell editors about my idea and most were like “that’s brilliant”. We now live three blocks from the beach, and I have a large work space in the Fountainhead Studios in North Miami. We have open studios twice a year, and curators, collectors, and general public pass through. Since I moved here in August I have worked editorially in Miami, New York City, Phoenix, Atlanta, Barbados, Panama, and Cuba.

RMC: The majority of the work I get is in Miami. Whether it’s musicians, climate change, or immigration, there is a lot happening here. I have had work in interesting group exhibitions here, and have shown elsewhere due to connections made in Miami. I’m also happier! I love the sun, the beach, paddle-boarding, surfing, yoga, speaking in Spanish or English, and the art scene. The city also interests me as a port city, and the so-called capital of Latin America. I am really inspired to make work here. Moving here has helped my career, I was given more jobs, and was able to build a better portfolio. Does Miami seem really far away from NYC? You just went to LA for a number of months. What did you go there and can you talk about your decision to come back? What is the difference between working in the two cities?

YM: All the things you just mentioned about why you like living in Miami is precisely the reason I loved living in LA this past winter and spring. I loved being surrounded by nature, going to the beach and hiking. I loved that I could be more spontaneous in LA. LA is a much easier place to live than NY – as everyone says “the quality of life is better”. I was like, ‘wow, life can actually be less stressful and easy.’ I can spend one day running around doing errands instead of three?! And I love driving! It’s been so amazing living in another city, which I’ve never really done other than when I lived in Israel when I was younger. I’m a born and raised New Yorker so it felt really exciting to step out of this bubble for a little bit. The move was initiated by my partner, photographer Cait Oppermann. At first I was so hesitant, but then I was like ‘why not?!’ I’m so happy I did it, but in the end, New York is home. As cliché as this sounds, I really missed the energy and hustle of NY. I kind of need that around me – it gives me more energy. Unless you’re on a big main street, you’re essentially living in the suburbs.

YM: As for work, initially I thought since there weren’t that many photographers living out in LA, I’d get so much work, but once I got there, I realised it’s just that there aren’t even as many stories being made in LA. Maybe that’s the reason why less photographers live out there? This led me to pitching more stories, which I’m happy about because I’ve learned over the past year how important pitching is. Pitching ideas to publications is so helpful towards creating and controlling the kind of work you want to make. In the end though, it was really the change of pace, the type of work I was getting and it’s just too chill for me. I found myself losing my NY alertness – I was leaving my wallet everywhere and driving off of curbs. I was becoming too chill for my own good. Although, I’m so happy we tried it out. It’s also great to know another place like you know your home. I had a lot more ideas for personal projects in LA than NY. Did you find that happened for you once you moved from NY to Miami? Miami is weird in its own way and I think you’ve done a great job at capturing its strangeness and creating interesting scenarios with people you’ve found there.

RMC: You are a real true New Yorker! I can imagine if you were raised in this city it could be really hard to leave, it’s amazing, and there’s so much energy flying around everywhere. I agree professionally it is a very good place to be, with lots of stories to be told and collaborators to be found. However, I find it great that you were open minded enough to come and experience something different and great that you did find work in LA, too. I love the plant images you made there, maybe it brought something out of you different than New York, and you never know where that will bring you. As for me and Miami, I definitely have more time for personal work, and feel more inspired in general. I’m inspired by the multicultural and multilingual mosaic of industrial, residential, and commercial neighborhoods that coexist in Miami. It’s disorienting, but also spiritual and captivating. I’m experimenting with different ways to make work there, photographing in the industrial spaces of Miami, juxtaposing them with more intimate, and corporeal scenes. Miami is on the forefront of climate change and immigration right now. It’s a city that people have always passed through and I’m interested in provoking a familiar feeling of disorientation felt in almost any modern city. However, even though I feel that I’m addressing some of the same issues or questions that I am concerned with in my editorial work, I still constantly question the relationship between the two. I think about how my voice changes depending on what platform I’m publishing, and how acceptable journalism standards can help and also hinder. How do you find connections within your personal and commissioned work? Is that something that you can reconcile through pitching projects? How do you delegate time for both?

YM: I actually learned I had a real knack for pitching when I was photo editing. Almost every issue that went to print while I was at the magazine had an idea of mine in it. It felt really exciting to come up with something, see it come to life so quickly and then share it with tons of people. I was happy to put people on and excited about getting new artists, collectives and ideas out there for the readers. I’m also really into producing , so since leaving the magazine, I’ve made sure to pitch stories I care about to publications I know will care too. I left the magazine a bit before Trump got inaugurated so all my pitches since then have been very political. I find the more I pitch, and the more I get the work I want to make out there, the more I get hired to make that kind of work.

“Sometimes I think my motivation to create wavers between anxiety and adrenaline”

YM: Since leaving the magazine I’ve gotten many commissions that feel very me and I’ve been so excited to work on. Outside of editorial work, I have a very disciplined art practice too. Over the years I’ve made a lot of different kinds of work, both aesthetically and conceptually. Some work could be more easily translated to editorial than others. For a while I was working quite abstractly by fragmenting my images using in camera methods on a 4×5 and that felt very separate from my editorial jobs. But more recently, I’ve gotten back into photographing people, places and things in a narrative sense which could definitely been seen in a more editorial context. At this point though, editorial and my art do seem quite separate. I will get a job occasionally that feels like an idea I would come up with but mostly it’s separate. The way I balance art and editorial is really just through discipline – there’s really no secret but making time for it. It all depends on what kind of project I’m working on but if it’s something I can shoot at my studio/home, I will do that as many days of the week as possible. And the next week I’ll scan and edit the pictures and continue in that pattern. It’s just about consistency for me really. I feel really lucky to have gotten the education I did at Pratt because it gave me an amazing work ethic and made me feel so guilty if I didn’t make work week to week. I still feel that guilt now – I don’t know if it’s always the best thing, but it’s definitely stuck with me. If I go a week without making work or at least progressing on a project, I get relly depressed. But I have learned over the years there are more ways than one to work on a project. Since graduating, I have come at projects very differently and my process in making work has changed immensely – that’s been scary but also really exciting and freeing. Do you find that your process has changed over the last few years and you found yourself working in ways you didn’t think you could? Or accepting what you previously thought was unacceptable in your work?

RMC: I very much understand the internal pressure to create. Sometimes I think my motivation to create wavers between anxiety and adrenaline. It can be a little dramatic. I wish stress wasn’t such a motivator for me, but I guess it’s somewhat natural. For El Libro de la Suerte, I took trips to Cuba where I was fully focused on making images, and being in a country where there is a lack of internet helped distraction from the creative process. I have made personal work in this manner for some time, going to a specific place to make work for a specific amount of time, so when I am making work where I “live”, there are new challenges of time allocation, but I am trying to create a weekly practice of making images right outside my door. I am taking creative processes that I developed in Cuba, for example incorporating performance into my work, into my work in Miami. Depicting place has always interested me, but with an overtly objective narrative. When I was in undergrad, I decided I wasn’t going to be a photojournalist, because I thought all the rules were restricting and in some instances arbitrary. How could photography ever be objective when there was a frame? I rejected it so much, but I now find myself doing some reporting because there are issues I really care about (re pipeline story in florida) and to be legitimate, I have to reign in the creative hand a bit. If I want to be really direct, I do not mind now putting on the journalist hat. There are a few things I care about, and many ways to express them. I spent about 7 years before I started working founding and running an alternative arts platform in a squatter community by the Panama Canal, and that work was also another way to address issues of social injustice. Engagement is important to me across platforms. I do want to go back to alternative education at some point. I have resisted being defined to one category of creative producer. Speaking of career choices, where do you see yourself in 10 years professionally? What would you like to accomplish?

YM: Ideally, I’d love to make really good money off of commissioned jobs and then be able to take a month or two off and work on a project – or travel somewhere. Traveling – and food -is where I spend all of my money. I think it’s important to save but I also know the importance of spending money on something that’s going to make me really happy and educate me. I know a lot of photographers that get a few great commercial jobs a year and are able to take huge chunks of time off to pursue their own work. I would also love to continue getting commissioned work that really fits my interests and aesthetic. Getting gallery representation would make me very happy as well – I’ve been in several group shows over the past few years but it would be great to have something more solid and regular. I’m thinking about applying to grad school again over the next few years – although I’m constantly changing my mind about it.

YM: But, what I’d really love, is to open up a middle eastern coffee shop/small restaurant. I don’t know if that’s in 10 years but maybe down the line. I have amazing Moroccan/Israeli family recipes that I really want to share with people. There are definitely more Israeli restaurants opening up in the States, but this would be specifically Sephardic, which is way less common. Mostly, I’d love to feel comfortable financially (aka paying off all my student loans!) and not have to stress about money. What about you? And since we’re on the topic of the future, I want to ask you a question about the past. What are your top 3 favorite commissions from this past year?

RMC: In 10 years, I would like to have refined my brand and my message as an artist. I would like to be living in a more local and sustainable manner, and have a more permanent home and studio, living in nature with a potential growing family. Living and working more remotely in nature would require that I already have established connections with platforms that would disseminate and fund my work, whether that be galleries, museums, publications, or even other brands. At the moment I feel that I live month to month, in 10 years I would like to be living and planning year to year, or decade to decade, providing a little more stability. I would also like to re-incorporate alternative education in my practice.

RMC: I hope you do consider grad school, I had a great experience. I went to Syracuse for my MFA, where there were highly intelligent professors, and great funding opportunities. I was able to refine my interests as an artist and develop a large body of work. I think it’s also great to pursue your interests outside of photography, as potentially with your restaurant. I believe outside interests can inform and even enrich our artistic practice. This year has been great, and I have worked more than ever, and so choosing three assignments is proving very hard, which makes me feel very grateful. I love the freedom that Vice commissions give me. I can send Elizabeth Renstrom an abstract concept and she shows enthusiasm and trust. I am not so sure any other publication would have funded the making of the images I made for the Vice Photo Issue 2016, and for that I am grateful. I am really proud of the Everglades project I did for the Intercept. I pitched it to them, and if I am correct it was the first time the specific environmental issues had been addressed in national media, which is significant to me. I also, of course, have to mention the Romeo Santos cover for the Fader. I have listened to Romeo Santos and Aventura for years, and it was my first cover. The shoots also went really smoothly, and Romeo, for being one of the biggest Latin music stars – if not the biggest – contradicted any unpleasant stereotypes of celebrities. The Fader has really allowed me to develop a voice when shooting portraits and the editors I have worked with encourage individuality. What are yours?

YM: Mine would probably be these:

1. Lawn to Earth for The Outline was so fun to shoot. This was the dream assignment. I shot it a week after I got to LA and basically just got to drive around all day long and photograph people’s lawns. I shot a mixture of drought resistant lawns and completely dried up lawns. I drove through all kinds of neighborhoods from the East side of LA to the West. I’m obsessed with flora (I currently have 31 plants in my apartment – not kidding, it’s becoming a problem) and I think the desert plants people have in LA are perfect.

2. This shoot was for the new publication, Phile Magazine, which is self-described as “The International Journal of Desire and Curiosity.” I shot a zentai fetishist. Not only did I love this shoot because of the subject matter but also because I got to direct it 100%, which was really exciting. I picked the location, which is a place I’ve been wanting to shoot at forever – it’s this insane love hotel in the Poconos. There was a hot tub, pool, columns, a circular bed – it’s totally over the top. It was for their first issue, which is out now.

3. I’ve been getting some super fun assignments from Bloomberg Businessweek and I got commissioned to shoot a great story a few days before I left LA. I was sent to the Buzzfeed headquarters in LA to document their crazy video productions. It was so surreal, bizarre and scary to see the way they make their videos – it’s literally a factory. It was really fascinating to witness, which in turn made it really pleasurable to photograph.

RMC: I love the diversity and quirkiness of these assignments Yael, and I can’t wait to see what you create moving forward. Thanks for initiating this conversation, and I hope we can continue it. It’s refreshing to have frank business conversations, especially with other women in the industry. Many thanks also to Pauline for providing the platform for it.

YM: Thank you!!! And same to you! Also, I can’t wait until you’re in town when I’m actually here so we can see each other IRL again!

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.