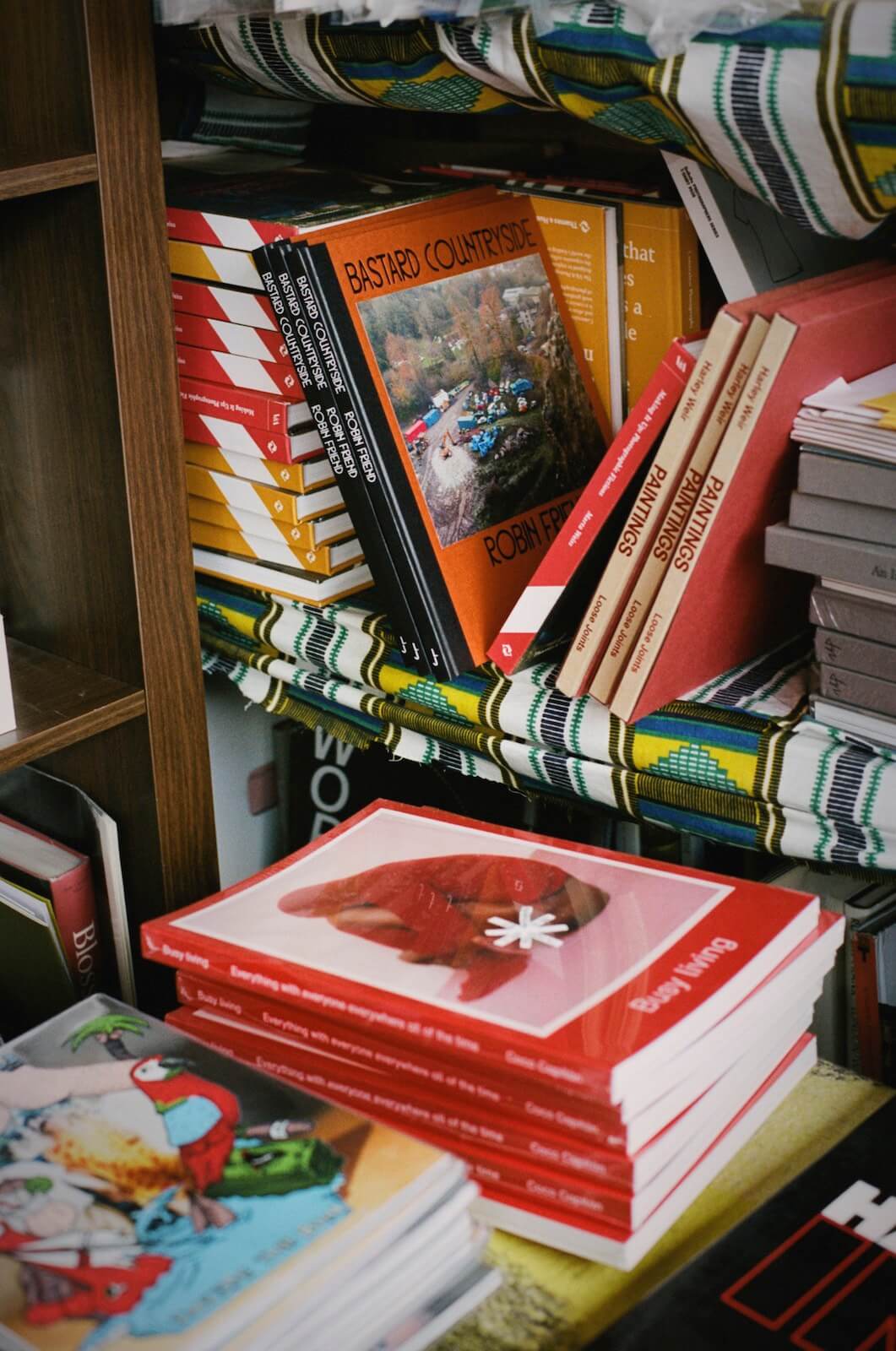

Studio visit with Loose Joints

Loose Joints is a publisher and design studio based between Marseille and London, founded in 2015 by Lewis Chaplin and Sarah Piegay Espenon. Loose Joints is dedicated to exploring progressive approaches to image making in book form. They take a holistic approach to publishing and design, working closely with artists, institutions and clients on all stages of a project from start to finish.

Beatrice Helman is a writer and photographer based out of Brooklyn, NY. Her work has been published online and in print in publications such as Vogue, Rolling Stone and The Cut. She received an MFA in creative writing at The New School, and her first chapbook Everything Melts Under The Sun will be published in the fall.

Suzie Howell’s work explores the boundaries between real and constructed narratives and often focuses on creating abstract, sculptural forms as well as incorporating traditional portraiture. Suzie holds a BA from London College of Communication and was recently selected as one of the finalists of Document Journal’s ‘New Vanguard’ photography prize and exhibited her work at Aperture Gallery in New York. Her clients include The New York Times, The Last Magazine, Port and the Financial Times. She is based in London.

Beatrice Helman: Hi Lewis, nice to meet you! You mentioned you’re moving away from London?

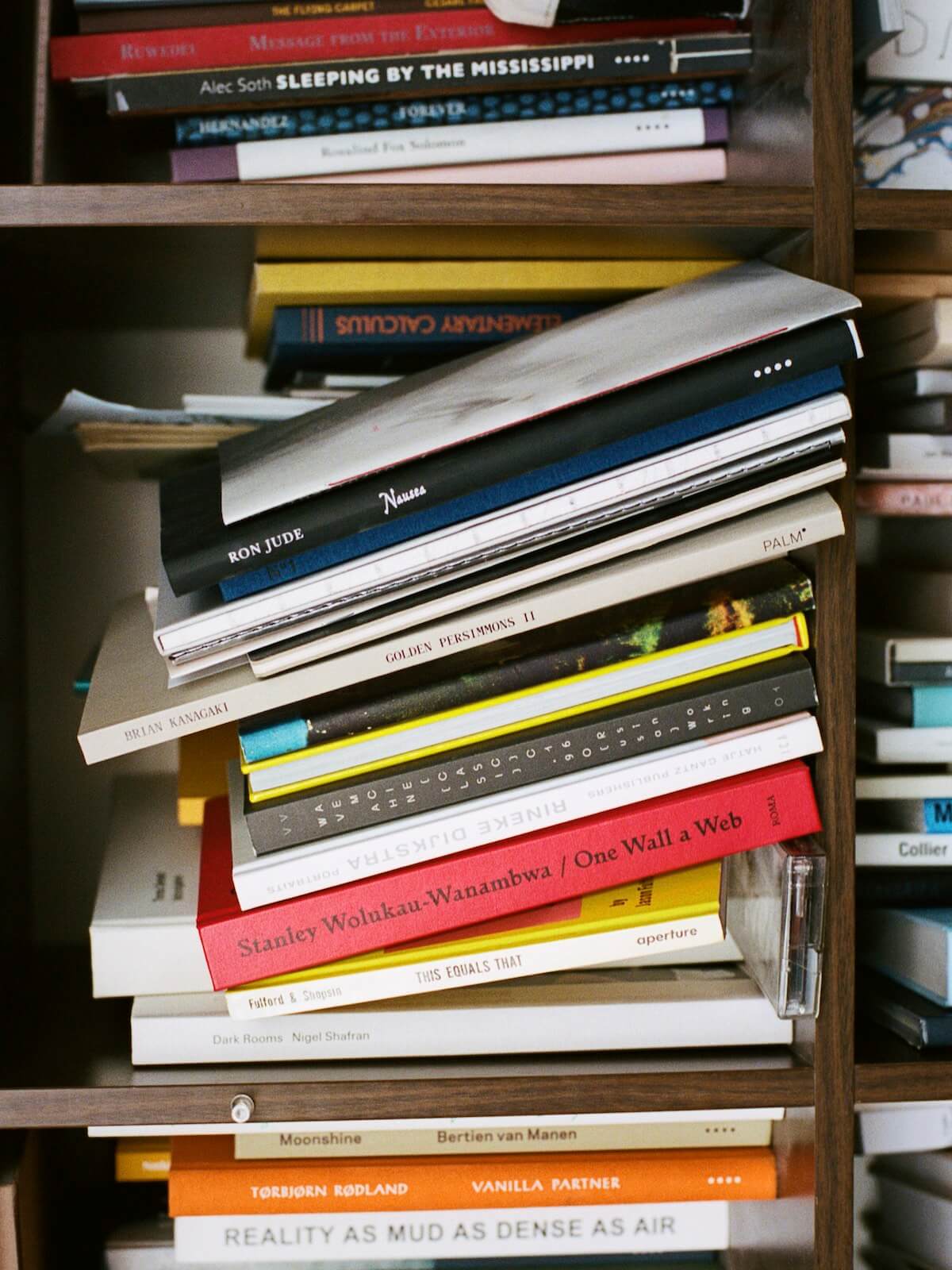

Lewis Chaplin for Loose Joints: Yes, Sarah and our cats have already left and I’m in our apartment on my own, with lots of boxes. Everything’s packed and I’m driving a big van on Monday. In fact, Suzie’s photos of us show the last day in our studio before we started boxing it up and dismantling everything so that’s a lovely memory to have. It’s strange when you know you’re leaving somewhere, you’re suddenly doing all these things that you’ve wanted to do for a long time. I’ve been cycling around for the whole day doing little things that I’ve wanted to do forever but put to the back of my mind.

BH: You really take advantage of the place in a way you didn’t before, when you’re leaving. Where are you moving?

LJ: We’re moving to the south of France, Marseille. It’s an exciting and beautiful city; it’s sunny and by the sea. Sarah is French, and we want to live somewhere where we can have a little bit more freedom to work on projects at our own pace, rather than living in London, which is one of the most expensive cities in the world. You have to work hard to get by – plus being a publisher is not exactly the most profitable vocation! We don’t want to have to compromise on the way we publish and design books because of where we live, plus it would be nice to be somewhere more relaxing. The more we’ve been designing and publishing books, the more we’re realized that we don’t need to be in London specifically. It’s so global, it doesn’t really rely that much on being specifically here anymore. So, why not?

BH: I think that as I’ve gotten older, more and more of my friends have started to leave New York and move to other places. When we were younger, we thought that we had to be here, that this was where you had to be to do everything you wanted to do.

LJ: That’s definitely happening in London as well. We think Brexit is a disaster. Not only on a cultural, political level as you see creativity leave the city, but also on an economic one. We print all of our books in Europe. We sell half of our books to Europe. Can you imagine the impact of the exchange rates? Suddenly, all of our book productions cost thousands of euros more than they used to.

BH: That’s a huge financial impact and definitely one that is going to be a problem for so many smaller businesses. Just to kind of rewind to the beginning of Loose Joints, how did you and Sarah meet and start working together?

LJ: We are a couple so we met that way, and then eventually we started talking about doing books and things like that probably about four or five years ago. We both have backgrounds in photography. Sarah studied fine art and design. I studied anthropology, but I’ve been doing things with books since I was a teenager, self-publishing, zines, running a book fair. The earliest things we did as Loose Joints were zines. The first thing that we did together was this book by Richard McGuire. It’s only 12 pages long, and is probably the only book we’ve ever published that doesn’t have any photographs in it, funnily enough. Richard’s a graphic novelist who also used to be in a post-punk band called Liquid Liquid back in the 80’s. He did this incredible comic in the 1989 called Here, which was this twelve-page strip where each panel of the comic was the same corner of a room occurring at different moments in time. It’s completely non-narrative, chaotic, but quite profound. It’s a beautiful thing, and just happened because we thought it would be nice to publish it, because it had only been published in a magazine in the 80’s. We emailed him off the cuff and he agreed. I think quite a lot of the early projects were like that, they were just about satisfying our own whim and curiosity about somebody, or about a subject matter, or a series of projects. And maybe that’s still what it is now as well, to be honest. We’ll see work and we’ll be curious about how it’s been shaped and we wonder, how could we help to expand it? And what could this be pushed or developed into?

BH: I’ve always been drawn to nonlinear, chaotic work and that sounds fascinating and beautiful. How do you ultimately choose what projects you end up working on?

LJ: It’s a real mixture, to be honest. Probably about half of the publications we put out are with artists who approach us. Sometimes we’ve known them for a while and it’s the result of a long, ongoing friendship, or at least a dialogue between them and us. People that we know and trust recommend us artists and sometimes we will reach out to people. We’ve used the momentum of us moving as a way to broaden our net actually and approached lots of artists that we’re really interested in, which we hadn’t done for quite a while. Sometimes you can get complacent when nice projects are always being flung your way, and not spend the time seeking great work out, which is something Sarah is great at. I don’t know if we could put a finger on what the criteria are. We mostly only publish contemporary/new photography and that’s pretty important to us. Anything that feels like it’s innovating a little or bringing a slightly new dimension to photographic discourse is interesting to us. Sarah and I have pretty broad tastes; we love difficult conceptual projects or photojournalism as much as good fashion and editorial photography. It just needs to have a particular kind of integrity to it, and some kind of a narrative that we can get behind as well, something that gives the work a little bit of context and purpose. This is always important even if a project is looser or more conceptual.

BH: Can you talk about some publications that speak to these two different types of experiences?

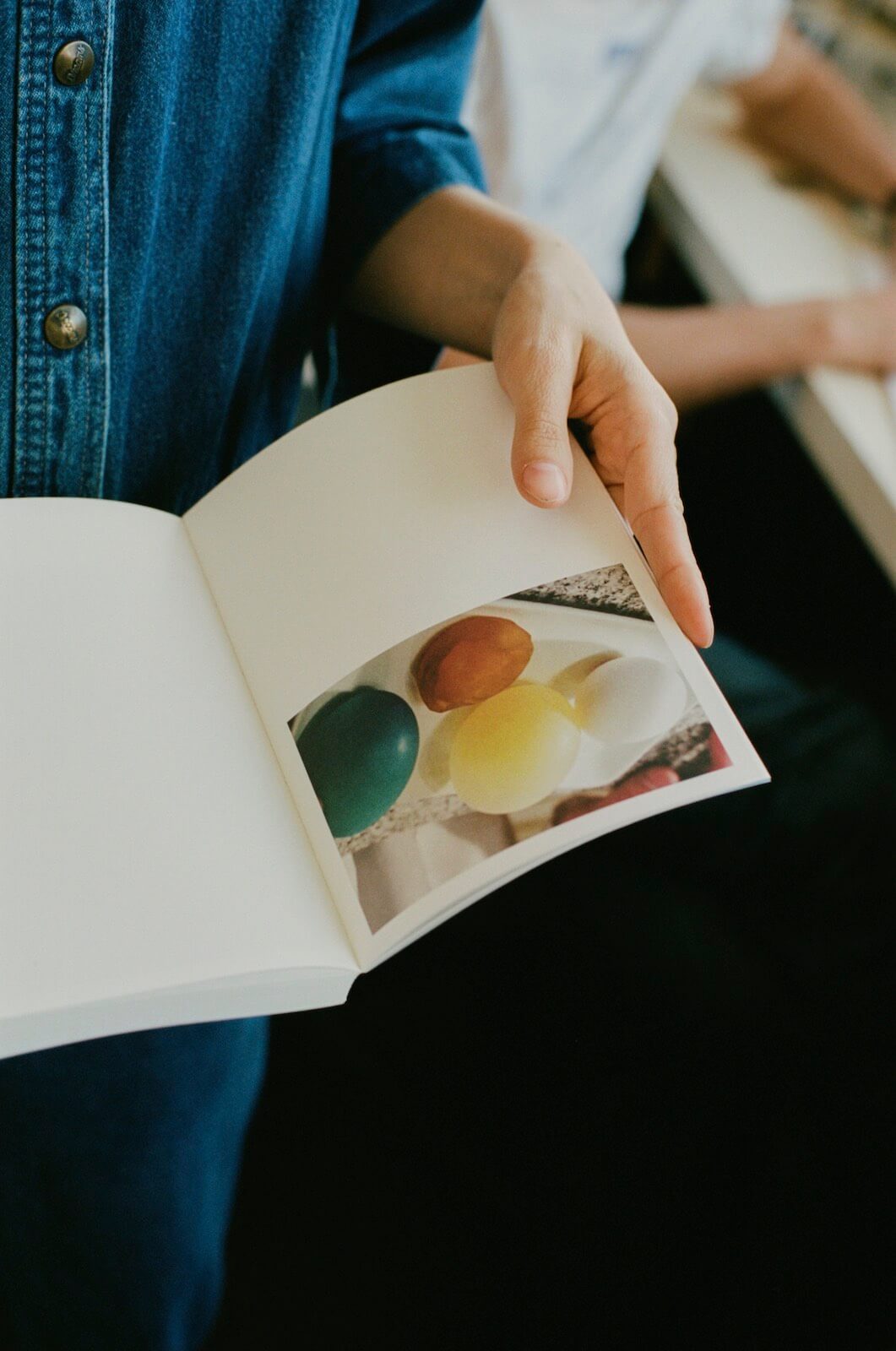

LJ: The first one that comes to mind is Seabird, by Bobby Doherty. Bobby is an old friend of ours, we’ve been friends both on and offline for over 10 years, since Flickr days. We’ve seen his commercial/still life/commissioned work develop and become more and more singular, precise and recognizable, to the point where we were in Ikea one day and immediately spotted a print of his on the wall from across the room. However, we also always knew that outside of the very clean, sharp sides of this work, Bobby had a much more natural, calm, personal output of constantly making beautiful photos on his old SLR, all the time, in the background. So after a bit of coaxing we convinced him to hand over about four years worth of photographs that he’d been making in private, which became Seabird. What we love is that you have that same creative precision and eye for humor, emotion, excess and color in these simple pictures as you do in his more staged work. And a book like this becomes a really fun conversation with an artist whose trust we’re very grateful for. We were given thousands of photos and printed about three or four hundred to physically sequence the associations and pairings of prints that make the book great. We think a book like Seabird is a great example of how narrative can be drawn out in a book just through the consistency and individualism of that artist’s eye, and we hope there’s a recognizable feeling throughout the book. The title is a nod to Seabird by the Alessi Brothers which maybe contains the same sweetness and simplicity to it that the photos communicate. For the cover – gingham fabric pops up a few times in the book and we felt like it has this everyday, comforting, pleasing quality that matched the photos well, so we asked Bobby to buy a huge piece of gingham and scrunch it up in his studio, play with it for a bit and in the end he delivered about 40 different options that we whittled down to the final cover, which on the desk at the correct angle also looks a bit like an optical illusion.

Another recent title that comes to mind is Congregation by Sophie Green. Sophie came to us with an early edit of Congregation images in the summer of 2017. We knew her and her work already, and we were immediately really interested in the series. Congregation looks at Nigerian Aladura Pentecostal Churches (sometimes called White Garment churches colloquially), and until recently we were based in an industrial area of South Bermondsey densely populated with these churches, tucked away in re-converted industrial spaces like warehouses or car garages, and with these incredible looking churchgoers and fierce 12-hour musical services. Sophie’s first edit was good but we felt it wasn’t substantial enough, or that more could be bought out of the project. She had already gained a level of trust and intimacy with what are usually fairly closed groups through running workshops there with the kids and having genuine exchanges with her subjects, and she had started making more posed, devised images, where congregation members were directing, styling and performing themselves a little more. So we encouraged Sophie to continue making photos for about a year and a half, which meant we had a really great involvement with the development of the project as we were editing and giving feedback every few weeks as the work developed. Sophie lived nearby to the studio so every month or two, we’d do a bit more sequencing, discuss design a little, and in the end the book came about nearly 2 years later. We never choose to rush a project – even if the artist wants to! – if we think it needs more work. Sometimes it’s really hard to find the right cover for a project and we went all around the place design-wise trying to get the right tone and in the end returned back to one of the first ideas, this strong, confident gaze on the front surrounded by luxurious white silk that mimics the garments within.

BH: Trust is one of the most important things in a relationship between artist and publisher and it’s very clear how much respect you have for the people you work with, how much you believe in them, trust their vision and how much they trust yours. You mentioned that you both just started doing it full time – what did you do before?

LJ: Up until recently, Sarah worked full-time in the arts. I’ve been concentrating on Loose Joints for about a year and a half and before that I was the book designer for MACK. Sarah and I also work as freelance designers on other projects; for museums and galleries, other publishers, artists wanting to self-publish or doing identity design. Doing these projects also allows us to also be a bit more loose and open-minded about the titles we release ourselves, what money we can put into it and whether we can do something ambitious.

BH: It seems like it would be helpful creatively to be able to work on a variety of design projects, both book and non, and a huge opportunity to kind of explore all different areas of design. Do you both do the design for all of your books?

LJ: Both Sarah and I design all of our books and we edit and sequence them together, this was self-taught and it’s come from trial and error and picking up stuff with experience along the way. But unless you’re lucky enough to have someone show you how it all works, you’re not going to learn about the more technical and nerdy side of things that are part of producing books. Papers, binding, printing… How to do all of these things well in order to make an object that is beautifully presented and sensitive but most importantly, that does justice to the content. We always try and be really open and transparent now whenever people ask us questions as it’s hard to pick up some of that knowledge without being in the right place at the right time. You’re not going to get taught it on a photography degree and only to an extent from studying graphic design.

BH: How do you interact, as designers, with the artist, as the creator of the body of work? How collaborative is the process leading to the final product?

LJ: There are particular projects of ours, like with Jack Davison for example. He was very keen on publishing something but unsure where to go with it, so he gave us a hard drive with thousands of pictures and in that case, we’ve had a really central, direct role in conceptualizing the whole thing. But it’s different with every artist. People might have a much better ability to edit and they might actually be very interested in doing it themselves, in which case we don’t need to get involved as much. Felicia Honkasalo, for example, whose book Grey Cobalt came out in January, approached us with a dummy that we thought was pretty good. We modified the design but the edit and a good part of the sequence of the book was Felicia’s. It varies with everyone. The projects we value a lot are the ones in which an artist will come to us and let us become part of the development of the project, like with Harley Weir. We have a new book by her and Cressida Brotherstone out very soon, a book about art therapy and creative play through art workshops. They were shooting and making pictures as we’ve been discussing the book, so our conversations about the edit happens as they get rolls of film back, and that becomes really interesting as the book and the work are being made at the same time.

BH: It is true that every book feels so individual and personal. Do you and Sarah both do everything?

LJ: Yes, we do – edit, sequence, design, production, repro right through to the end: overseeing the books being printed. Sarah’s better at editing and sequencing for sure. And she has really good design ideas that are sometimes more ambitious than mine, which is interesting. I do the technical stuff, layout, print production, logistics, repro. She’ll suggest things that I know are complicated or annoying to do. When you know how to make things easier for yourself as a designer it can be tempting, but Sarah often pushes projects into something a little more complicated but special. This is the side of book design and publishing that we like a lot, when you’re playing with restraints and you have to be smart on how you actually operate and finance and fund projects. How to balance something looking interesting, well-produced and doing the work justice but not breaking the bank. That’s a good, productive tension for sure.

BH: What happens when you get stuck? What are you looking at, what are you listening to?

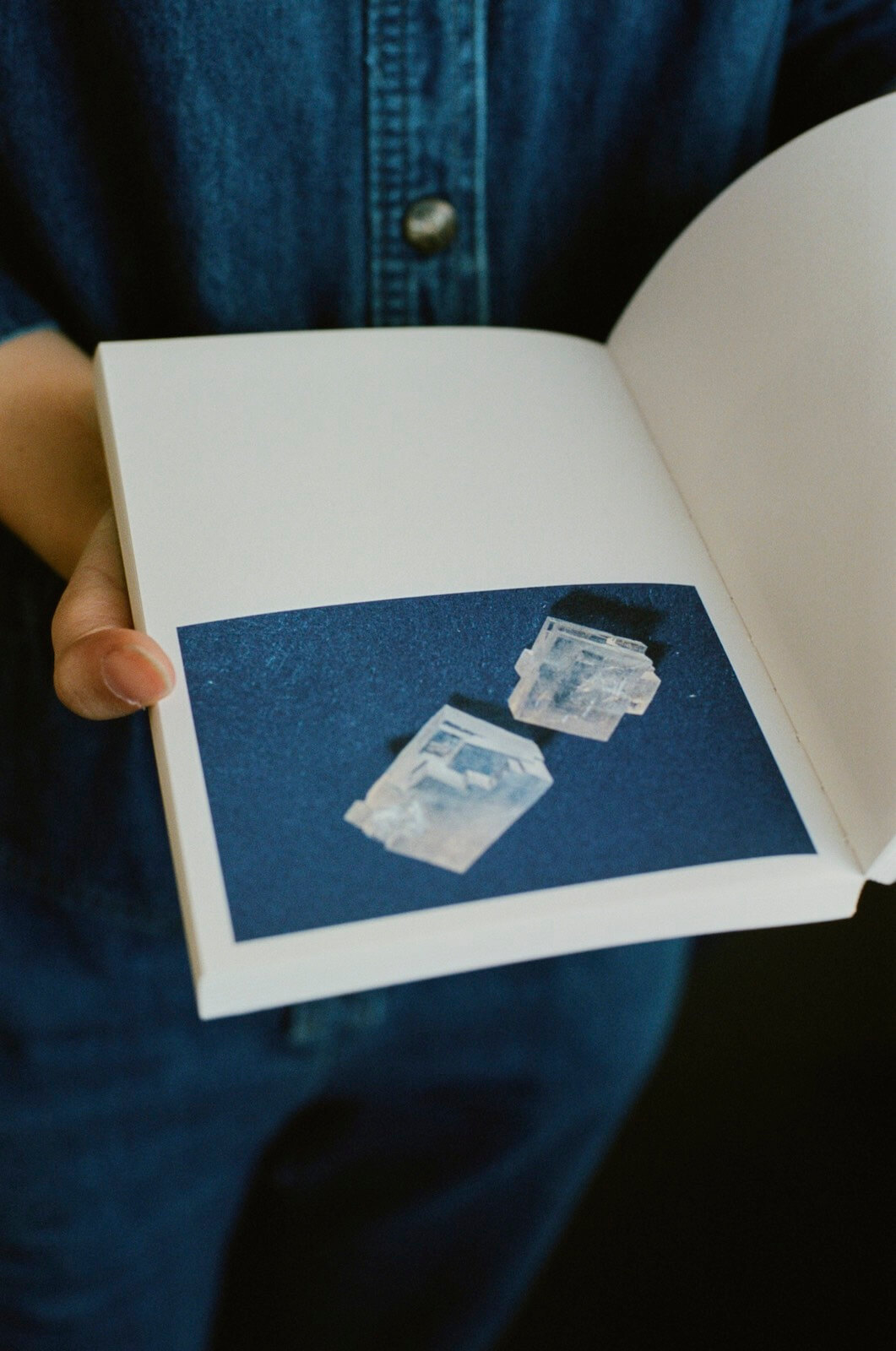

LJ: Generally the best thing when we’re struggling to find a feel for the design is to just keep looking at the photos and discussing conceptually where the work is coming from until associations come up. For us any design choices or physical qualities to the book need to be specifically connected to the nature of the work somehow, otherwise the design feels superfluous and irrelevant to us. We’re always questioning why any particular decision is being made. For us, any aspect of the book needs to feel like an extension of the work itself. In an ideal world, we would hope that people wouldn’t look at any of our books and immediately tell it’s made by Loose Joints. Physicality is also really important when it comes to bookmaking and we have tons of paper samples, tons of materials, tons of books so my go-to will often be just feeling and holding stuff and looking at things until an idea comes around.

BH: I completely relate to that feeling of being able to physically hold things and have tactile involvement with them in the creative process. To swing over to another kind of question, what would you say are the ups and downs of working as publishers today, in 2019?

LJ: The internet and the rise of ‘photobook culture’ is a relatively recent phenomenon in the 150-year history of the photo book, and we obviously as a publisher have profited well from this moment. It has allowed us visibility and a platform as a young independent publisher that previously might not have been accessible and possible to someone interested in releasing books in previous generations. However, the downside of that is that we are now working within an extremely saturated market, where the spectrum and quantity of publishers and books is at a very high level but we are also unsure whether the actual consumer market for photo books has actually expanded beyond a fairly select and specialized group of people committed to regularly buying photo books (and more importantly, who can afford it!). On the one hand this creates quite a positive pressure to ensure that the books we publish are as well-executed, thoughtful and accessible as they can be. In order to stand out from a large sprawl of other book publishers we think you can’t be as complacent as in the past with regards to design, print quality, accessibility, promotion, et cetera. On the other hand, when the consumer market for photo books is spread more thinly over a greater number of publishers, obviously you maybe aren’t seeing the revenue or order quantities that your Scalos or Steidl’s of the 90s might have expected…We’re very keen to not get too comfortable at any point. We think there is often a moment when an art publisher gains a good position in the market and then can become complacent about design, production values, editorial standards.

The other huge up and down for us is the environment. Sarah and I care a lot about it and about the well-being of our planet and therefore have a complicated relationship with our own status as publishers. We love what we do but we question the sustainability of it, and the relevance of it in the grand scheme of things (which in turn also depends on how romantic your opinions on the importance of art are!). Obviously it is quite easy to go after a book publisher and assume that someone responsible for cutting down trees is a greedy and significant contributor to environmental degradation, which isn’t strictly true. A printer once told me to think about trees for books as being grown as a crop, just like wheat or potatoes, they are grown for specific purposes and then replanted. This is true at least for the suppliers we work with – we’ll use only recycled or FSC-certified papers and processes, and we are about to introduce some other options including carbon offsetting on each order, carbon neutral delivery, biodegradable packaging. We have also stopped flying and are opting for the train…So this is a huge up-and-down, knowing that what you love is directly something that extracts natural resources from an already fragile global ecosystem… But such is the guilt associated with any indulgence in 2019, and rightly so. It is a complicated time to be a publisher but also we’re interested to see how our practice is shaped and responds to the changes and challenges of the coming years.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.