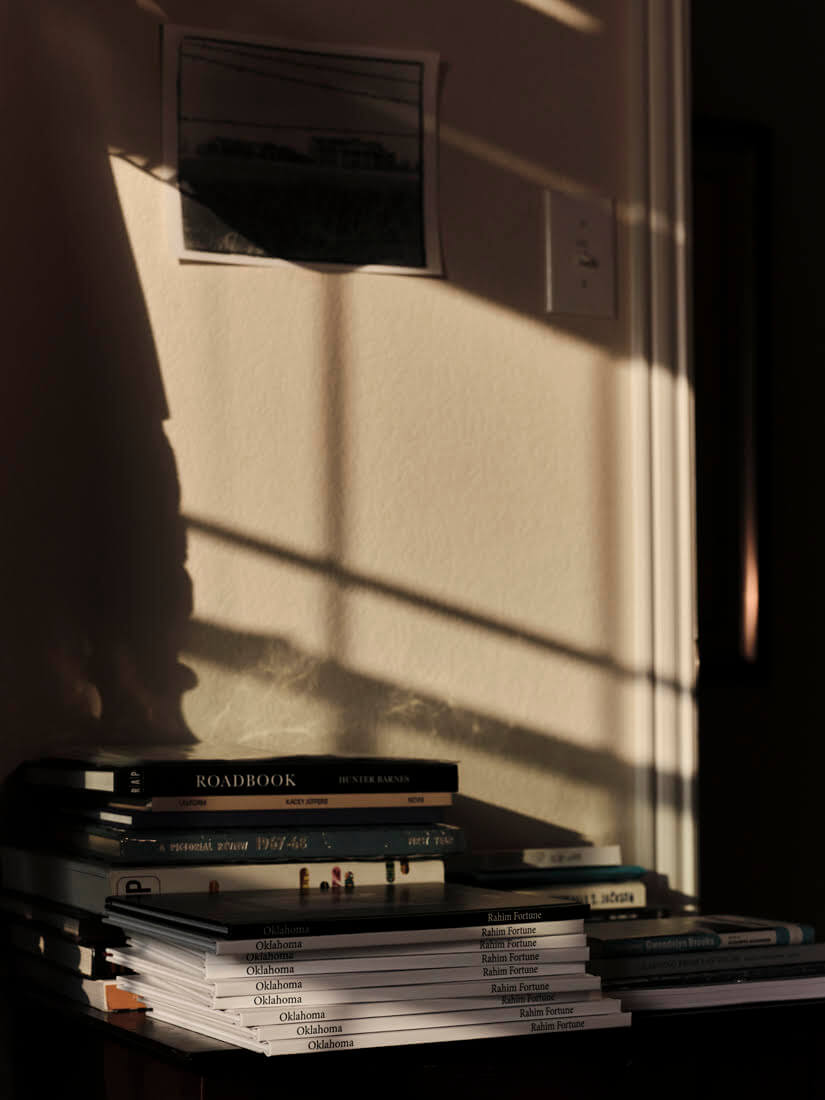

Studio visit with Rahim Fortune

Rahim Fortune is a fine art and documentary photographer from the Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma. His work focuses on culture, geography and self expression.

Marcy Ayres is a photo producer and photo editor specializing in food, travel and portraiture, currently she works at The Wall Street Journal. Previously she was, a senior photo editor at Culture Trip, and in her free time she likes to work with metal and talk about art!

Photographs by Gem Hale

Marcy Ayres (MA): Tell me how you have been, it seems like you have been busy over the past few months?

Rahim Fortune (RF): Yes, it’s been interesting. I feel like the business has come out of the discord previously, people didn’t really care too much to be honest. I’ve been making the same type of photos since 2016 and it’s just now that society contextualizes the photographs, versus vice versa. I think that’s why a lot of the people who I was spending years assisting are now congratulating me. It’s really an odd kind of dynamic to watch unfold during the quarantine as well.

MA: I’ve seen you in the New York Times now almost every week, weekend and then on the cover of New York Times magazine. How has this all really affected you and your work?

RF: I can’t really say how all of this success is affecting me without saying that this all happened while my father was transitioning. He passed away three weeks before our conversation. Part of why I came back to Texas during the quarantine was just to be with him. And that’s re-visioned history because the way it really happened was I came to Texas on March 8th. And then on March 12th, I had the last job that I did in Virginia Beach. I was assisting [on a shoot] for Warby Parker, just very normal, the pandemic was starting to ramp up. I got back to Texas on [March] 15th and that’s when New York shut down. I was like, oh wow. It might not be an option just to go back. I ended up just being here in Austin and it was interesting for me because I had already put in a lot of work to have a successful year with photography. I had been working really hard to produce some of my own personal editorials, like a piece I did for Suited Magazine titled ‘Modern Composure.’ That was a project on the classic musicians. That was the first project where I really did everything, start to finish; it wasn’t assigned. I was really ready to have this big year and then everything shut down. I still have that energy of really being hungry for work. I just began making photos of whatever I could. That’s where it started. I was able to break down a lot of barriers within photographing, for example, in my house and photographing my family. It would be a week-long process of thinking about asking my family members to make a photo because your attention that comes with the way they are in front of a camera, your dynamic, where they think you’re coming from wanting to take the photograph… There’s a whole multitude of things.

MA: And how you see them and how they’re portrayed within the image.

RF: Especially when you’re dealing – because I’m dealing with my father’s illness at this point. He’s paralyzed. Previously photographer friends would be like, “Oh, I’m sure you’re making excellent work of your father right now.” And I’m actually not. I was between New York and Texas, but when I was in Texas, that barrier was able to come down during quarantine to make a body of work that I love. I would say this is where it starts, but a lot of those things about photographing my father and his illness and photographing my grandparents and their old age and my sister and her transitioning into womanhood, they really kind of set me up for a lot of the assignments that I was going to end up getting. The biggest one I will say is the New York Times Magazine cover. I’ve said it multiple times that if it wasn’t for my work as a caregiver working so closely with medical staff in my home with my father, I don’t know that my experience [on that] would have been the same. It would have been a completely different thing. It was almost as if I was qualified for it because I had dealt with the illness and death a lot in a very compassionate way, caring way. That was a moving assignment and it was life changing.

MA: I see that you have a book coming out in the spring with Loose Joints as well. Was that in production before all of this or how did that come about?

RF: No, that was somewhat recent. They had asked me if I had anything that I was considering publishing cause I ultimately feel as though books will be the best way for my work to live than in an exhibit. I really do enjoy assignments, but it’s really about finding the right ones. And if you want to be a working photographer, good assignments aren’t just happening all the time. You have to wait for good news stories and writers to do a lot of research. I hope to think that I will leave a good amount of books behind that articulate what I’m interested in, but Loose Joints reached out and they asked me if I had anything I had been working on. I told Them about the project that I had been working on, around my father and the quarantine and just trying to contextualize this time as a personal moment, but also a national moment. I don’t want to give too much away about the book, but there are some challenges that came with the subject matter that I’m really excited about working on because it is not going to be straight forward, like putting-photos-on-paper process. There’s going to be some type of conceptualization. That’s going to be required to make the project read correctly. I’m excited to work on that.

MA: That’s awesome. I’m really excited to see the work that you made during this time. So you’re from Texas. What part are you from?

RF: I was born in Austin, Texas. In 2003, I moved to Oklahoma with my mother. And we lived there until 2007. That’s how the body of work in Oklahoma came to be. All but about eight years of my life had been spent in Texas, and then the other two in Oklahoma.

MA: How would you say growing up in the South and especially seeing it compared to living in New York city has affected your work and your style of photography?

RF: [When] I moved to New York, I was just a portrait photographer, but I was also a young photographer. It wasn’t until I came back to Texas that I started to notice the architecture was so different. From a colonial standpoint, a lot of our architecture intersects with colonial history. In New York, these old 1700s buildings are built more economically sound, but in Texas, you really feel the sense that some of these towns are just thrown up and a couple of buildings and the architecture was starkly different. I wanted to learn how to capture that, what that really meant. When I first started, my first photos of people were published through Heavy Collective and I really didn’t know what I was doing, but I would later come to find out about the new topographics and the visual language of photographing the new American landscape. That was really a pivot for me, moving just from portraits into trying to capture landscapes and details.

MA: You seem to really be able to find that sense of place and the things that are interesting, within them, just on the street, which is not something that everybody can do. Also going from the south to NYC and seeing the different architecture, because the North has a different history and even weather conditions – and even a different sense of community. To me, your photography is really about community and the ground building relationships and photographing them in a way that is not as voyeuristic, but feels more like you’re a part of the community. How would you try to encourage that? Or let people know that this is an important and viable field or style?

RF: It all starts with reading. I understand that there’s a lot of challenges with that, especially with the quarantine. Within the quarantine, I’ve found it hard to read because my mind is just so overwhelmed. Literature relates back to your work. And for me, it was critical race studies. A lot of critical race studies and historical texts really inspired my work. I’m really into photo history, I think that understanding photo history is critical to understanding how to make work. My type of work is fixed within photo history. I like to play with some of these themes. Knowing as much as you can about the medium you’re working within and about exactly what it is that you’re trying to say. Because once you start to figure out certain themes, you start to figure out how those themes can be represented, and then you might go looking for them or you might see something in the real world and they say, ‘‘Hey, that represented the theme.’’ You might not capture that time, but you continue. It’s a constant rolling cycle of figuring out – I had this thought process one day that really just evoked me the beauty of siblinghood or something like that. Or you read a piece of text that talks about mending bonds of things and just things like that that are really sentimental and taboo or difficult topics to get to and figuring out ways to work that out visually. It’s always difficult, and that is why not everyone is a photographer. One of my favorite quotes is from Mark Steinmetz: Good photos are terribly hard to make.

MA: Do you have any music or playlists or albums that are a must listen to when shooting or editing to really get you in that artistic sensibility?

RF: Yes. Three artists: Khia has an album called Your Girl Forever. Very great album. That next one is Starchild & The New Romantics. Excellent, excellent musician. A brilliant album just came out from him. And then the last one is a gentleman named James Tilman. So those three artists, they’re from all over the US, but they’re New York based. Three musicians who are definitely bridging the gaps musically, and a lot of the stuff that they do was very inspirational to me because I often think of photography in terms of music. I am a musician and my father was a drummer. I think of photography and visual genres almost like a musical genre in the way that they’re formulated and the way that they take shape around authenticity and aesthetic. A lot of that music I feel is very in line with my work. It’s this perfect play of the past and the present.

MA: Awesome. Thank you so much, this was a wonderful conversation and I can’t wait to see your new book with Loose Joints.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.