Teresa Eng on Wong Kar-Wai

Teresa Eng (b. Vancouver, Canada) is a photographer who lives and works in London, England. Her work explores the inevitability of change through personal histories. Teresa’s projects explore the psychological state of trauma (Speaking of scars 2008 – 2010), the impact of technology on the representation of self (Self/Portrait 2015), the fragmentation of identity in the diaspora communities (China Dream 2013 – 2017) and the changing nature of neighbourhood and cities (Elephant 2013 – present). Teresa was awarded the 2020 Martin Parr Foundation Bursary, 2019 Burtynsky Grant and was a finalist for the 2019 Aperture Portfolio Prize, Images Vevey Book award and Hyères 33e festival of fashion and photography. Her first book, “Speaking of scars’, was shortlisted for the 2013 Aperture/Paris Photo First Book Award.

Wong Kar-Wai is a Hong Kong film director. His films are characterised by nonlinear narratives, atmospheric music, and vivid cinematography involving bold, saturated colours. A pivotal figure of Hong Kong cinema, Wong Kar-Wai has had a considerable influence on filmmaking with his trademark personal, unconventional approach.

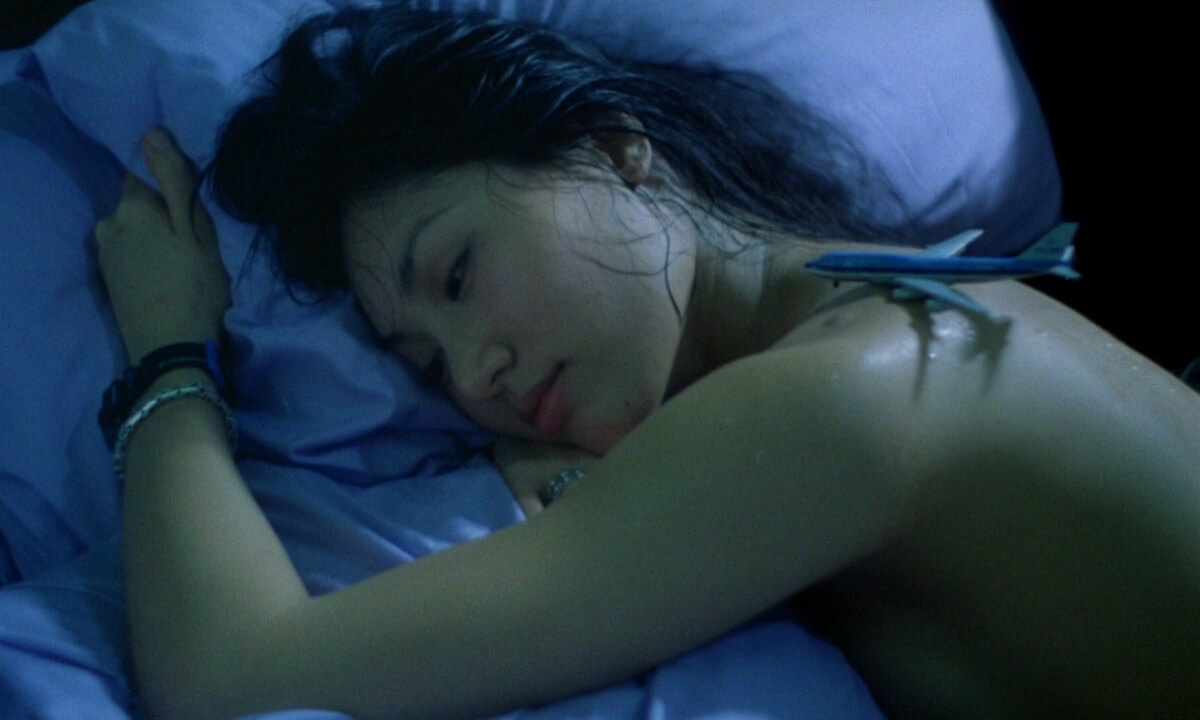

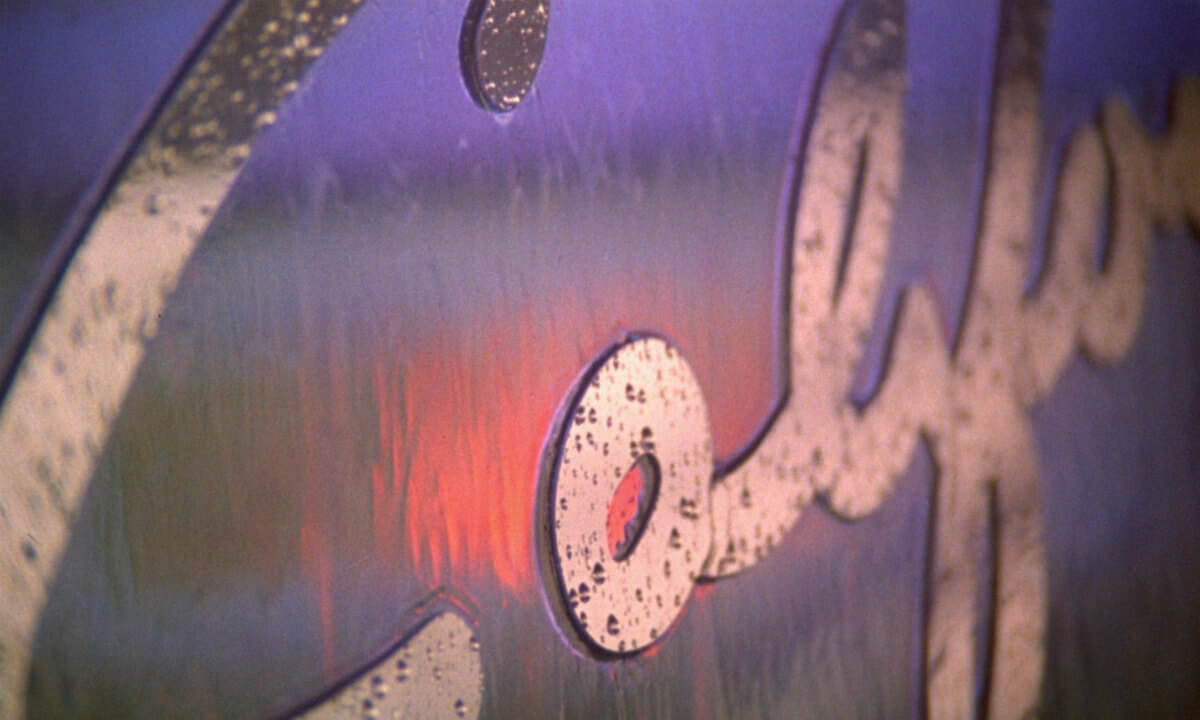

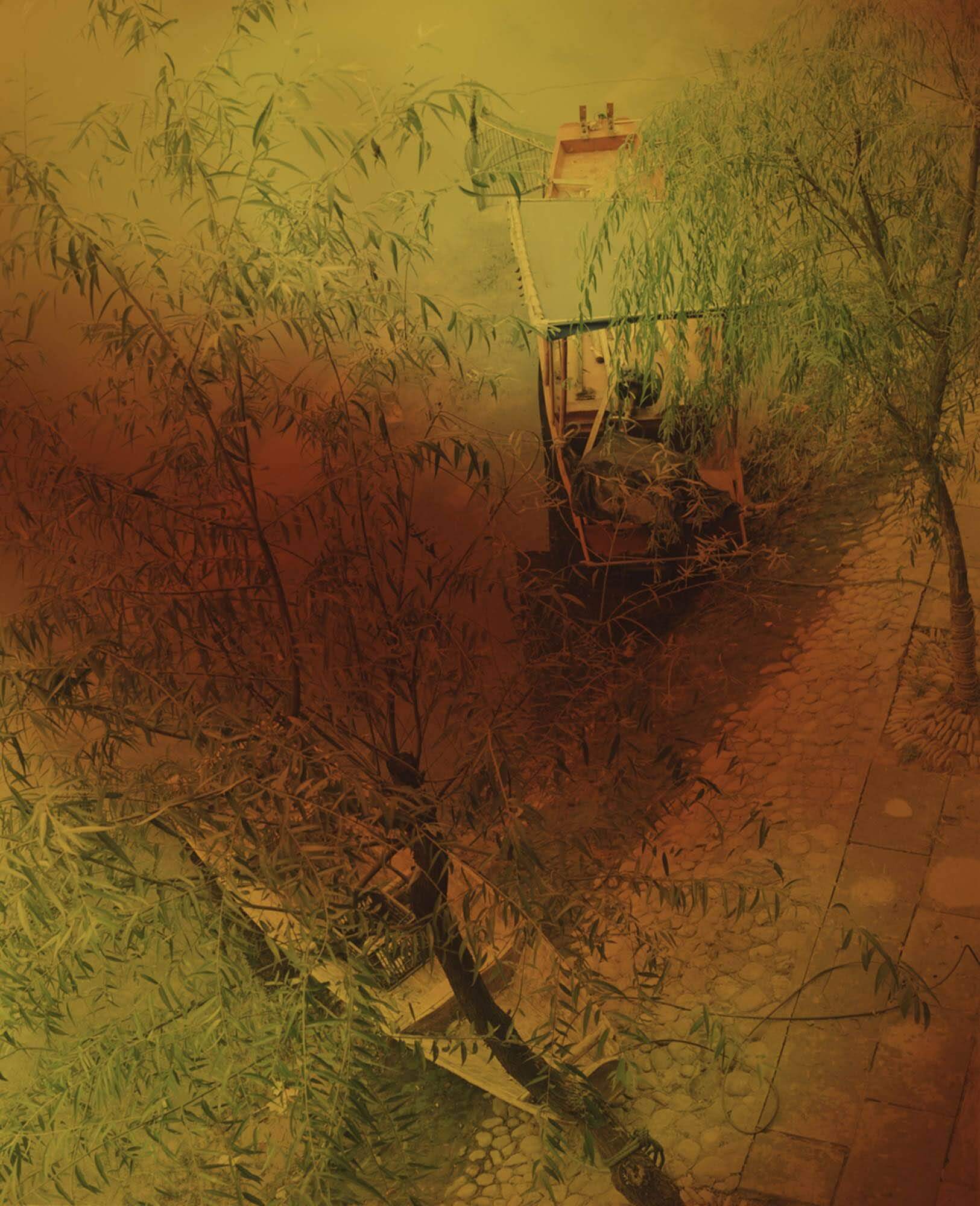

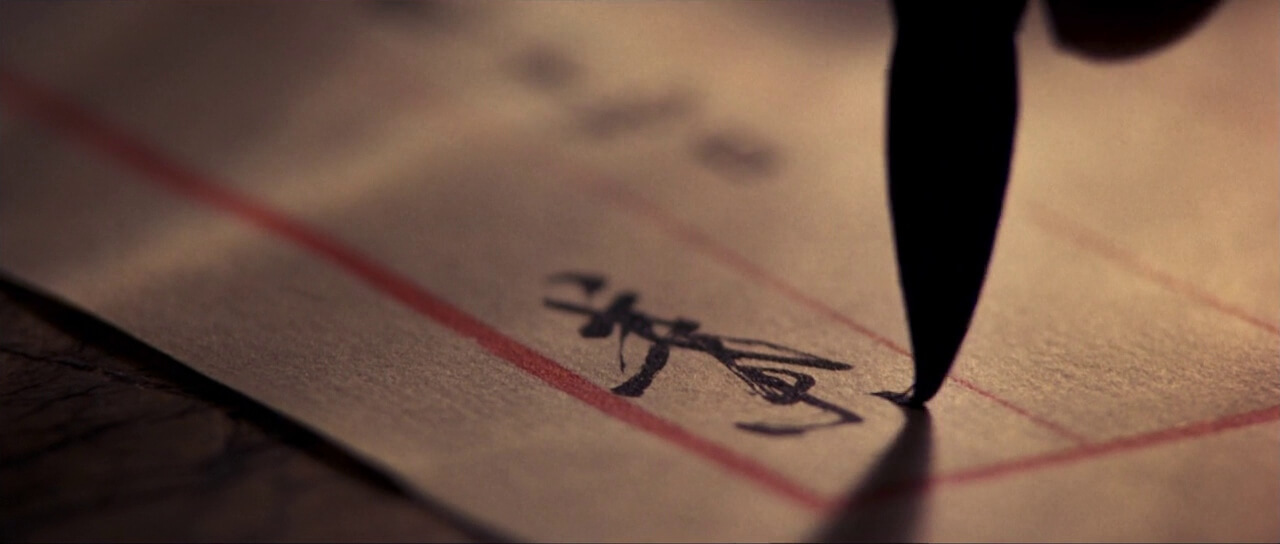

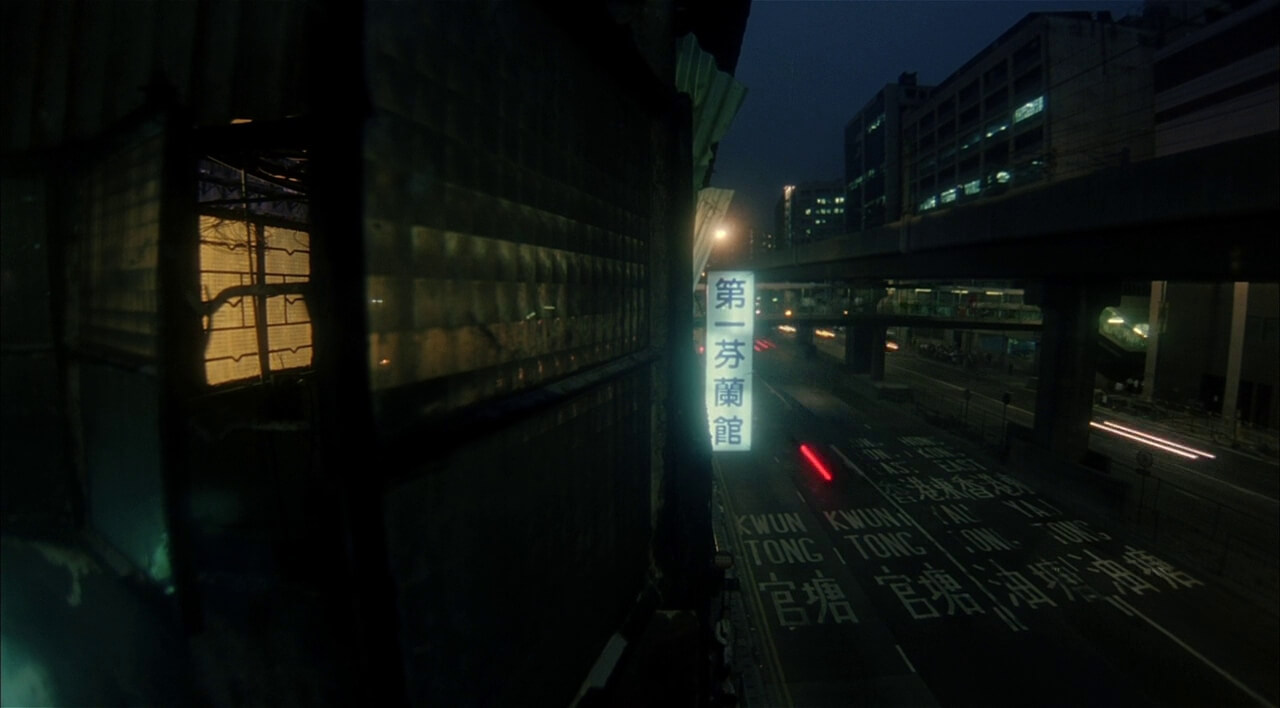

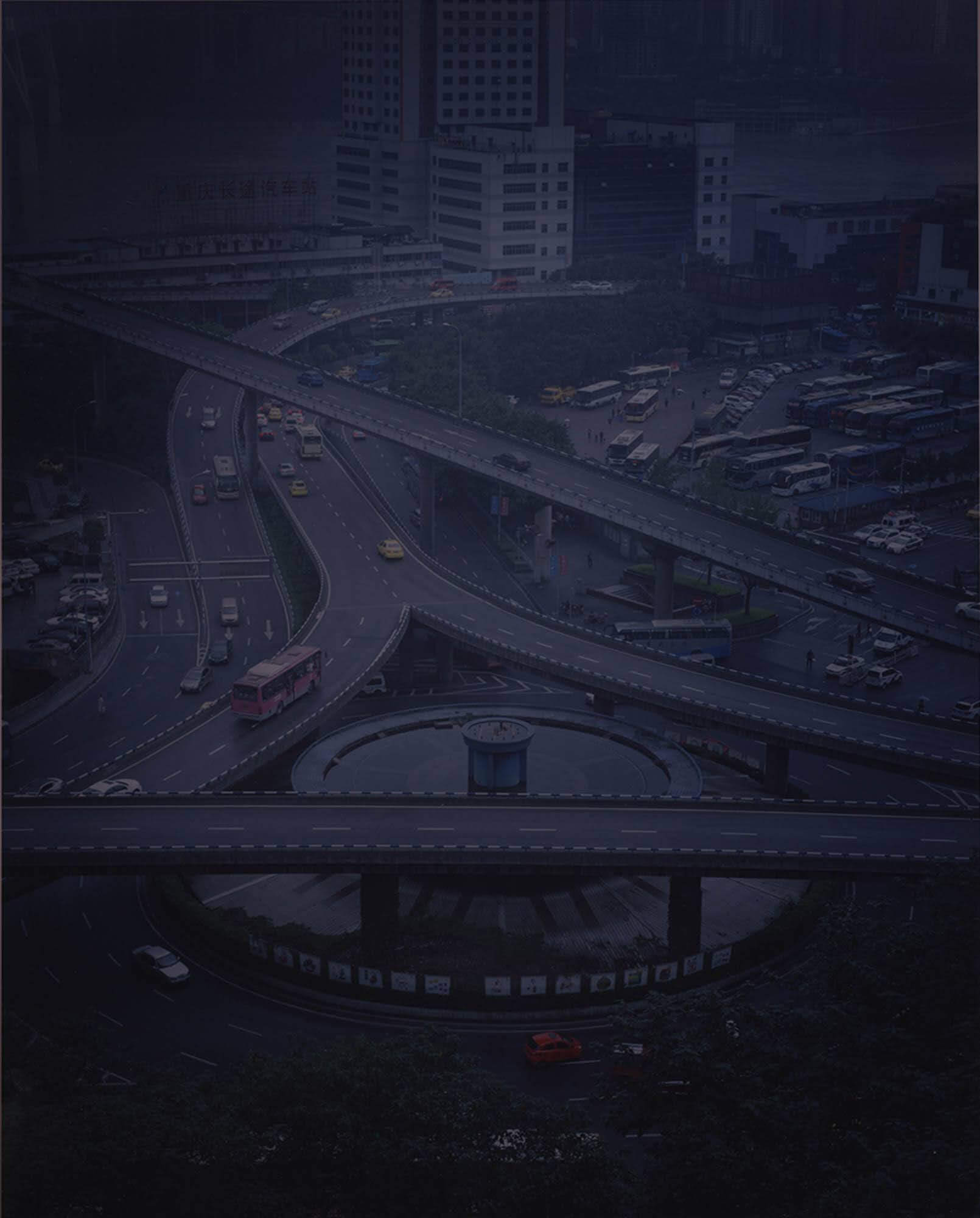

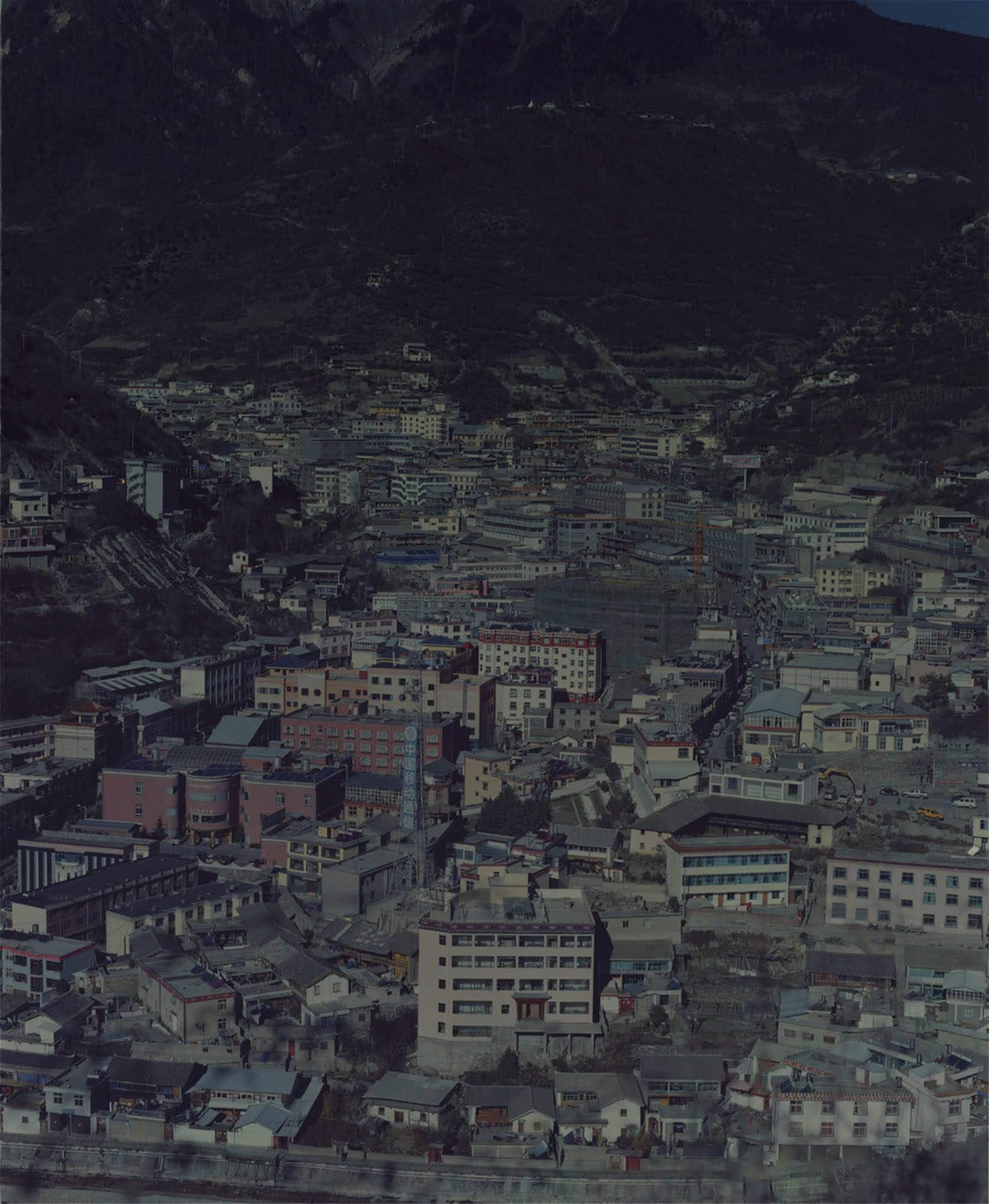

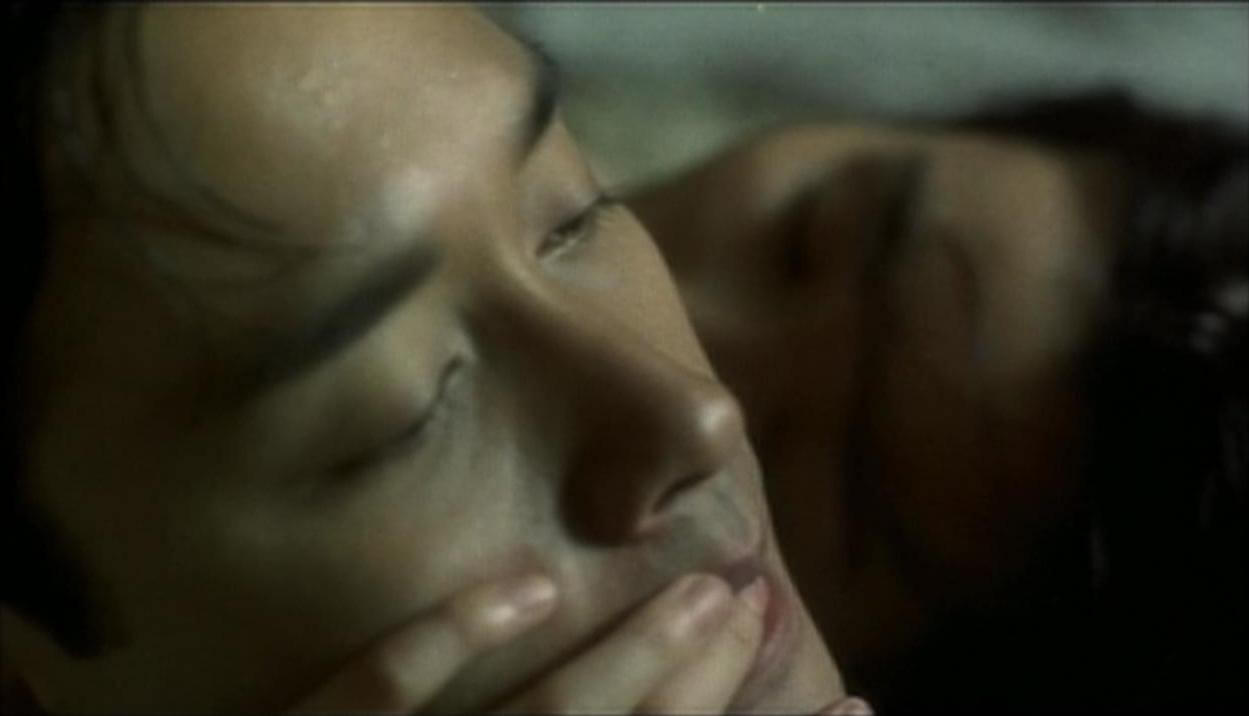

1: Screenshots from Wong Kar-Wai's movies, 2: Teresa Eng, throughout the article.

When I was growing up in Vancouver, my parents would take us to one of the Chinese movie theatres to catch the latest exports from Hong Kong. The movies we watched ranged from police thrillers and triad/organised crime to ghost stories with hopping vampires and slapstick comedies (parental guidance was an afterthought). It was low-brow but it gave moviegoers an escape from the daily grind and a connection with their homeland.

As I got into my late teens, a friend introduced me to Wong Kar-Wai’s Chungking Express. It captured the energy and mood of Hong Kong that looked nothing like what I watched as a kid. The film features two lovelorn policemen (known as Cop #223 and Cop #663) who are pulled out of their misery after encountering two unconventional women. The film was made on a shoestring budget and shot on the fly with handheld cameras to avoid paying for location permits. The music in the movie weaves the vibrancy of the city with 60s American classics like The Mamas & Papa’s “California Dreamin” and Dinah Washington’s “What a difference a day makes” with Faye Wong’s Cantopop version of “Dreams” by The Cranberries. It made it cool to be Chinese but more importantly, it gave first-generation kids like myself a creative role model to aspire to. It countered our immigrant parents wish for stability and hopes that we would become doctors, lawyers or accountants.

As I watched all of Wong Kar-Wai’s films, I entered a world which explored loss and melancholy. He eschewed linear storylines, instead he focused on the interiority of his characters. He used his characters’ innermost thoughts to narrate his film, expressing what couldn’t be said. I would sit in the theatre, transfixed by the subtle changes in his actors as they sought to hide their emotions. He used music to highlight those moments as they repeated throughout the film. Those songs would replay in my head long after I’d seen the film, reminding me of specific scenes from the film.

Wong Kar-Wai uses time to highlight the fragility of relationships. Chance encounters brought lone strangers together briefly before they moved on with their lives. Relationships are measured by minutes as clocks feature throughout his films, reminding us of the moments lost.

This awareness of time acknowledges Wong Kar-Wai’s childhood in the 60s. He and his parents moved from Shanghai to Hong Kong as the Cultural Revolution gained hold. His other two siblings didn’t join them until ten years later as the border between Hong Kong & China closed. He struggled to learn Cantonese, the local dialect of the region, furthering his sense of alienation. He would recreate that period of change in his films Days of being Wild, In the Mood for Love and 2046. His characters, arrived from Macau or China, live in cramped conditions, renting rooms from families as the influx of new arrivals from China swelled. The 60s was a time of political uncertainty as numbers of people immigrated abroad in response to the anti-colonial riots, China’s growing power and the uncertainty of Hong Kong’s future when the country would be handed back to China in 1997. Although he wasn’t overtly political, current events and newsreel footage appeared in the background of his films.

Wong Kar-Wai pushed the boundaries of filmmaking in a commercially driven culture. He worked with a revolving cast of 80’s Cantopop royalty and movie stars who returned to play characters that flitted between the past, present and future. His cinematographer Christopher Doyle, art director William Chang and stills photographer Wing Shya created a unified vision with colour and composition. In The Days of Being Wild, lush imagery and green tones set the story of a rebel without a cause who goes to the Philippines in search for his birth mother. In 2046 and In the Mood for Love, the pastel blue and green tones of the film’s set design and costumes complement the rich blacks and red-orange of the film. Happy Together tells the story the volatile relationship of a gay couple, Ho Po-Wing and Lai Yiu-Fai in a fragmented and restless way. As their relationship disintegrates into a cycle of on again, off again drama, the film changes stylistically moving from black & white to the acid hues of cross-processed film.

Although I’ve never met Wong Kar-Wai, the way he edits sound and moving image together has influenced the way I approach photo books. I think about the edit and sequencing of images as akin to a musical composition in which the layering and connection of motifs create a form of visual poetry. With my latest book China Dream, I wanted to the explore the complexity of identity and the Chinese diaspora as we navigate between the country in which we were born and the culture that we inherited from our parents. By visiting my ancestral homeland over a period of four years, I attempted to see beyond the visual and audible noise of the city and reflect on China’s tumultuous history in the past century. There was also an underlying existential question of how different my life would have been if my parents had remained in Guangdong province instead of migrating to Hong Kong then Canada.

Wong Kar-Wai’s films have taught me how to see the world in its details. China Dream presents these fragmented aspects of the cultural traditions that I inherited, the stereotypes that I grew up with and the reality of a country undergoing rapid urbanisation. In Happy Together, Chang spends his time listening to voices, citing that bad eye problems made him a good listener: “You can pretend to be happy but your voice can’t lie. You can see everything by listening.” It’s the paying attention that spurs me to create work which I hope will connect with people in a way which they can feel.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.