Vasantha Yogananthan in conversation with Matt Dunne

Born in 1985, Vasantha Yogananthan lives and works in Paris. In 2014, he co-founded the publishing house Chose Commune and published his first book, Piémanson, which was nominated for MACK First Book Award and Kassel Best Book of the Year. In 2015, Vasantha Yogananthan was the recipient of the IdeasTap/Magnum Photos Award (category international) to help him fund A Myth of Two Souls, his project on the Ramayana in India. In 2016, he was awarded the Prix Levallois and in 2017, he was awarded the ICP Infinity Award as Emerging Photographer of the Year as well as the Foam Talent prize.

Matt Dunne is a photographer based in Canberra, Australia and is the co-founder of This on That. He has received a Bachelor of Arts in Literature and History from The University of Melbourne. He teaches at a High School for traumatized and at-risk youth.

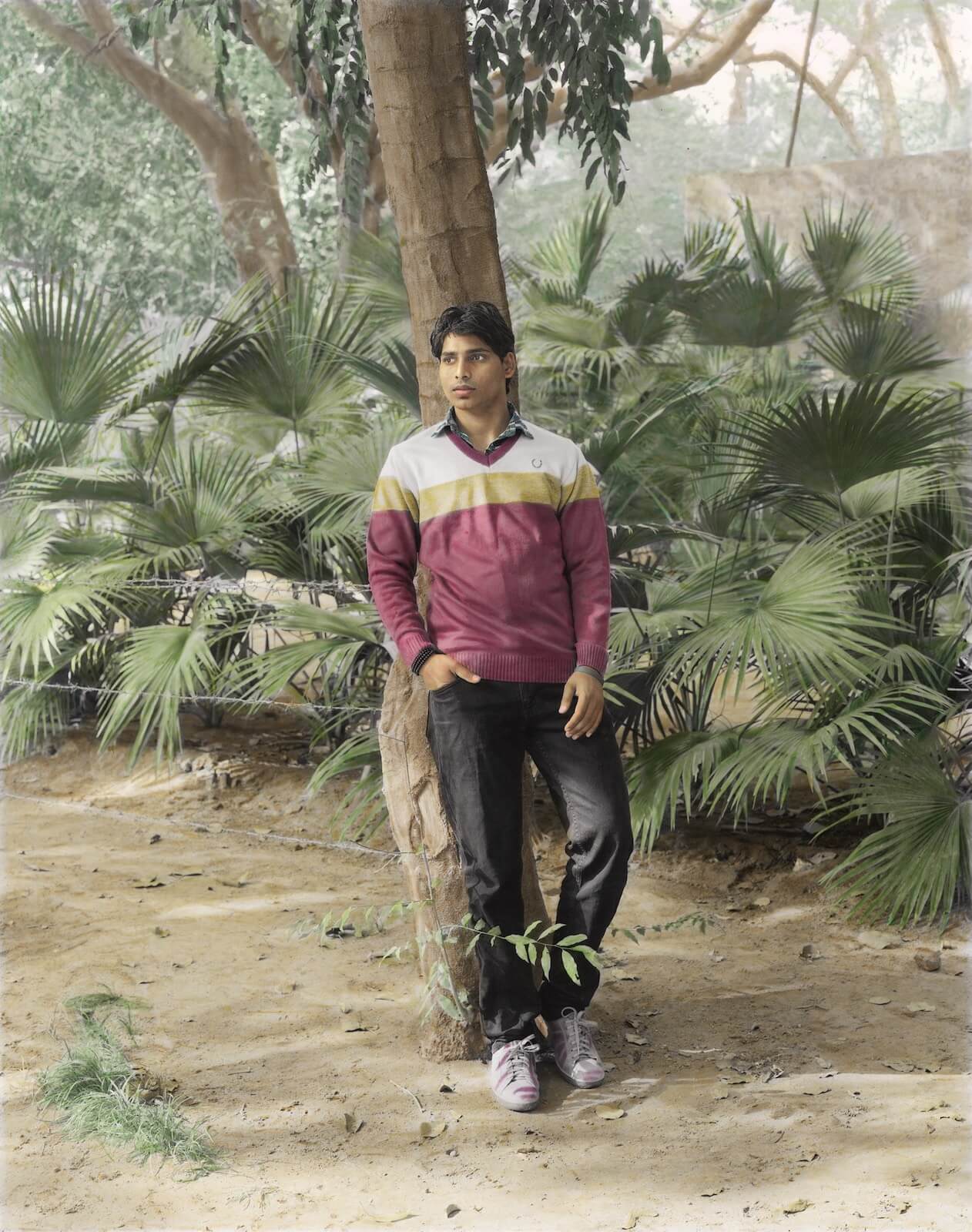

Myth of Two Souls is inspired by the epic tale The Ramayana. Drawing inspiration from the imagery associated with this myth and its pervasiveness in everyday Indian life, Vasantha Yogananthan is retracing the legendary route from Northern to Southern India. First recorded by the Sanskrit poet Valmiki around 300 BC, The Ramayana has been continuously rewritten and reinterpreted, and continues to evolve today. Yogananthan’s series is informed by the notion of a journey in time and offers a modern retelling of the tale. A Myth of Two Souls juxtaposes several sets of photographs: landscapes, hand-painted staged portraits and illustrated black and white photographs. The landscapes are mythical to Indians today as they were described in the original version of The Ramayana. In the portraits, inhabitants of these landscapes stage scenes that have left a mark on their imagination. Shot in black and white using a large-format camera, these theatrical portraits have subsequently been colored by an Indian artist using the ancient technique of hand-painting. Through classic color, hand-painted and illustrated photography, A Myth of Two Souls interweaves fictional and historical stories with a narration that takes viewers on an epic journey. A Myth of Two Souls will be published in seven photobooks between 2016-2019, one per chapter of the tale.

Matt Dunne: I’m interested in hearing about how your memories of ‘The Ramayana’. Do you remember what you thought when you first heard it? Has your opinion or relationship with the epic changed over time?

Vasantha Yogananthan: My first memories of The Ramayana are a bit vague. As a kid I was looking at the comic books – the most popular version of the story – but I could not read English so I was only looking at the pictures. Twenty years later, I bought an abridged French translation and I remember being blown away by the story. Everything we experience in life was there. Of course, my relationship with the epic side of the story has shifted over time. After five years of work – seven trips and still counting – I now know a lot more about The Ramayana and the issues it raises. I have read countless different versions of it. In India people use to say: “there is not one Ramayana but three hundreds Ramayanas”, and this is what makes it so intriguing.

MD: Furthermore, I wonder if you feel that the poem has contemporary relevance for India? Does it still say something very meaningful about Indian society, or Indian people?

VY: The epic is still very relevant in contemporary India. Because of the themes it tackles – family, love, honour, rape, purity – it is subject to multiple interpretations. Right-wing political parties try to use it to disseminate the idea that India is first and foremost the nation of Hindus. Women writers have been retelling the epic from its heroin’s point of view, questioning the status of women in India. The Ramayana is used for countless advertising, from real estate, tourism and so on. Because the story has been modernised over time, the younger generation knows it as well as their grandparents do. Only the medium through which the story is told has changed. A hundred years ago, bards were travelling across India to sing the epic in villages, now people discuss it on WhatsApp.

MD: It seems that this epic poem is incredibly pervasive around the world – why do you think it’s managed to become so wide spread and worldly? Do you think that it defines a lot of Indian culture?

VY: The Ramayana is pervasive in Cambodia, Indonesia, Bali and most of Southern Asia. It has even crossed the borders of religion. It is fairly easy to engage with because it is a universal story. The epic interweaves with the Indian culture. It is fully part of it. Images from the tale are everywhere in the streets. Common sayings refer to the story.

MD: You’ve mentioned in previous interviews that the locations of the Ramayana are real – and that anyone can visit them in India. Is this how you came to the locations where the photos were taken, or do you visit other locations?

VY: The locations were mentioned in the first written version of The Ramayana (300 BC). The names of the places have not changed. You can follow the itinerary from Nepal to Sri Lanka, making your way through the entire Indian sub-continent. A funny example is that Makemytrip (one of the biggest online flight booking Indian company) made a Ramayana website entirely dedicated to its locations. You can follow Rama’s footsteps and for each locations, they tell you which flight you need to book and where you can stay. The fact that the story is geographically grounded in real locations is also what makes it so important to Indians.

MD: How do you edit this project? Given that you’ve chosen to split it into 7 chapters, are you editing one work at a time, or editing all 7 simultaneously? What does an ‘editing session’ look like for this project?

VY: It is like a giant puzzle slowly building up. Because the Ramayana is divided into 7 chapters – each one telling a specific part of the story – it was the most interesting (and crazy!) way to approach it. Each chapter and book is different. The first chapter was about childhood. The second about love. The third one about exile and losing all material possessions, etc. Like in every good story, each chapter should come as a surprise for the reader, and makes him eager to know what comes next. I have these seven folders on my computer. Editing-wise it is a bit of both: working on one book at a time while thinking of the bigger picture. The hardest part of it all is to gauge between each trip which pictures or material I am still missing. There is this pressure of producing work, which at the same time freaks me out while being super exciting. It would have been much easier to wait for the project to be done and make one big book. But we’ve opted for the more challenging way instead. The editing itself is done in close collaboration with my partner Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi. We have co-founded our publishing house together, Chose Commune. Once we have a first sequencing, we meet with our designers Kummer & Herrman, who are working on all seven books with us.

MD: This project seems just about as collaborative as it’s possible to get. From talking to the people who pose themselves for you, to allowing the tradition of professionals hand-painting black and white film, there are many facets of collaboration taking place in ‘A Myth of Two Souls’. What led you to this level of collaboration, is it something that you think you’d like to continue?

VY: When I started researching about The Ramayana, I quickly realised there were already many people working on and around it, especially in India. Building a collaborative project allows me to have multiple voices telling one story. It is hard, it demands a lot of energy, a lot of dialogue with everyone involved (writers, artists and painters) but it is very fulfilling. I’m working on a much smaller project in France at the moment, and the process is the complete opposite. No texts, a very loose story, pictures only. I work alone and it feels so good.

MD: How do you improve as a photographer? Do you expect that the final chapters will show improvement from the first, if so how do you feel about that?

VY: The deeper I get into the project, the clearer my vision becomes. I remember the first three trips: I was really lost. The pictures were either too literal or too far away from the story. I don’t speak a lot about technique but after I started working with a large-format camera during my third trip, the way I photograph had changed. I slowed down and started doing these staged portraits with the locals. I had never staged a picture before. When I think of the sixth chapter, which is about war, I know I will have to shoot in a completely different way. It keeps me going because the possibilities are endless – you just have to be creative and be careful not to ever stay too long in your comfort zone.

MD: When I’m looking at work online I’m lucky in a sense that I see the successes, but I’m curious about the difficulties. During this project, so far, what worries or anxieties have you had to deal with, or are still dealing with?

VY: Well… There has been a lot of failures. I shoot analog so I don’t see what I do while travelling. When I come back to Paris I go straight to the photo lab to have the films processed. I wait for a week and these are the worst days of the year. I always think I might have fucked it up – that I did not do well enough. Working on the books is also stressful: you need to make the story easily accessible to a wide audience while telling it in a complex way.

MD: I want to ask you about publishing others’ work – how does publishing others’ work vary from your own? Do you have a very hands-on approach, or do you step back and let the artists do most of the editing and design themselves?

VY: I love publishing other photographers’ work. It makes me stop thinking about my own practice. I am grateful to get to work with other artists and learn from them. As these are not my pictures, I am much more confident in what we should do to convey the work successfully. Cécile and I always do the editing and sequencing together. We work with designers but we are always closely working on the book concept. When we are happy about the directions the book is taking, we present a first version to the artist and the dialogue can then start. We have never worked with a ready-to-print dummy.

MD: Finally, I’m curious as to what you do to relax, and how it helps you slow down a bit?

VY: Walking in the wilderness is what relaxes me most. I love the sea, I love the countryside. I love the mountains. I come from Grenoble, which is a small city near the French Alps. I used to go snowboarding twice a week when I was a kid. I can never stay too long in the city, I have to head out to find peace.

Rocket Science has been featuring the best in contemporary photography since 2016 through interviews, conversations, studio visits and essays by photographers, writers and artists. Your donation to Rocket Science directly supports new artistic content in the pages of Rocket Science and helps us pay our contributors fairly.